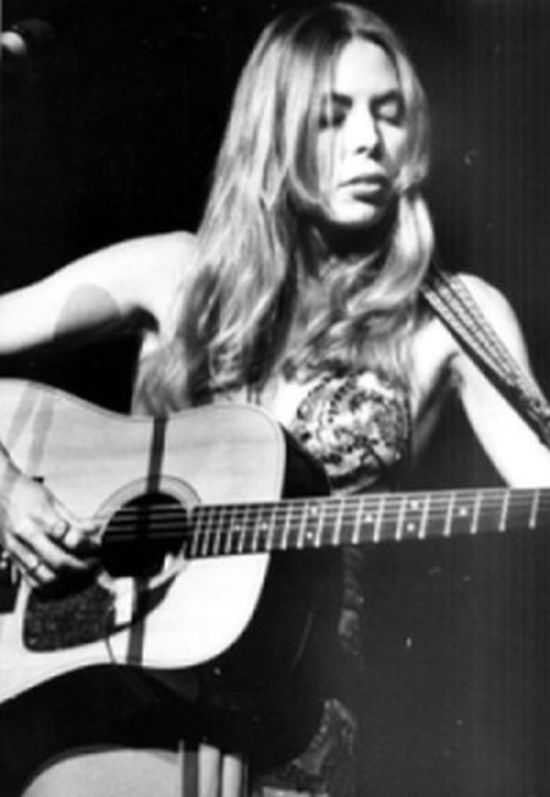

Joni performing during 1974 tour

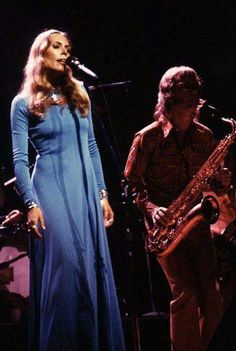

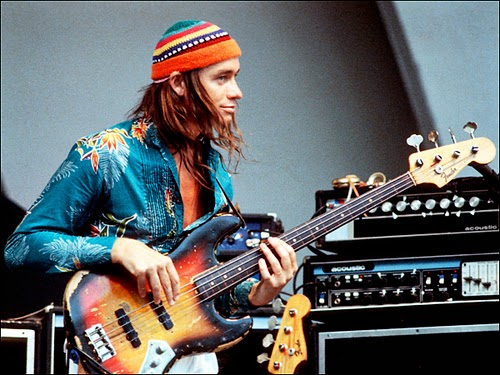

‘Miles of Aisles’ features beautifully rendered solo performances of songs from the ‘Blue’ and ‘For the Roses' albums. The album also includes re-workings of 'Big Yellow Taxi', ‘Rainy Night House’, ‘Woodstock’, ‘Carey’ and 'You Turn Me On, I’m a Radio’, utilizing Tom Scott and the L.A. Express to create new jazz and blues shaded arrangements for these songs. The recording opens with an announcer expressing “our pleasure to introduce - Miss Joni Mitchell” followed by Joni's acoustic guitar playing a country flavored riff, leading into a laid back rendition of 'You Turn Me On, I'm a Radio'. Robben Ford plays sliding guitar lines at the end of the song that Joni mimics with her voice, using the top end of her vocal range. Her scatting vocal creates a stunning opener as she responds to and intertwines with Robben Ford's guitar. She gives a powerful rendition of 'Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire', forcefully strumming her guitar with Tom Scott playing a bluesy clarinet accompaniment behind her. She finishes the lyrics with the line 'Come with me I know the way she says, it's down, down, down, down, down...', her voice trailing off into silence as she sings the last repeated word 'down'. Joni's guitar and Tom Scott's clarinet finish out the song. Joni leads the audience in a sing-along during the choruses of ‘The Circle Game’, prefacing the song with a monologue about how performing music is different from the art of painting, concluding her analogy with “nobody ever said to Van Gogh ‘Paint a Starry Night again, man!’ You know. He painted it, that was it.” During her performance of 'The Last Time I Saw Richard', Joni takes on the character of the cocktail waitress, speaking the line 'Drink up now, it's getting on time to close' in a nasally voice that gets a laugh from the audience. ‘Both Sides Now’ serves as representation of the ‘Clouds’ album and a performance of ‘Cactus Tree’ recorded at L.A. Music Center the previous March is included as an entry from ‘Song to a Seagull’. Although several songs from ‘Court and Spark’ were performed during tours with Tom Scott and the L.A. Express, ‘Peoples’ Parties’ is the only one that appears on ‘Miles of Aisles’. In a moment between songs, while Joni is tuning her guitar, a fan is heard calling out from the audience “Joni you have more class than Mick Jagger, Richard Nixon and Gomer Pyle combined together!” This remark gets a big laugh out of Joni. The crowd is obviously completely on Joni's wavelength and she uses their outpouring of affection to reward them with exquisite renderings of her music. Joni introduces the last two performances of the two record set, ‘Jericho’ and ‘Love or Money’ as new songs. According to Simon Montgomery, who compiled the Chronology of Appearances on the Jonimitchell.com website and served as one of the consultants for the the 2003 PBS American Masters program, 'Woman of Heart and Mind', these last two songs are not recordings from the 1974 summer tour. 'Jericho' and 'Love or Money' were actually recorded in a studio with audience reactions added to the mix to give them the sound of live recordings. Apparently, Joni wanted to include these songs on 'Miles of Aisles' and they do show up on the set lists of some of the 1974 summer concerts. Perhaps since these were two new songs that had not been released on any other of Joni's albums, a more controlled environment was wanted for their recorded debut.

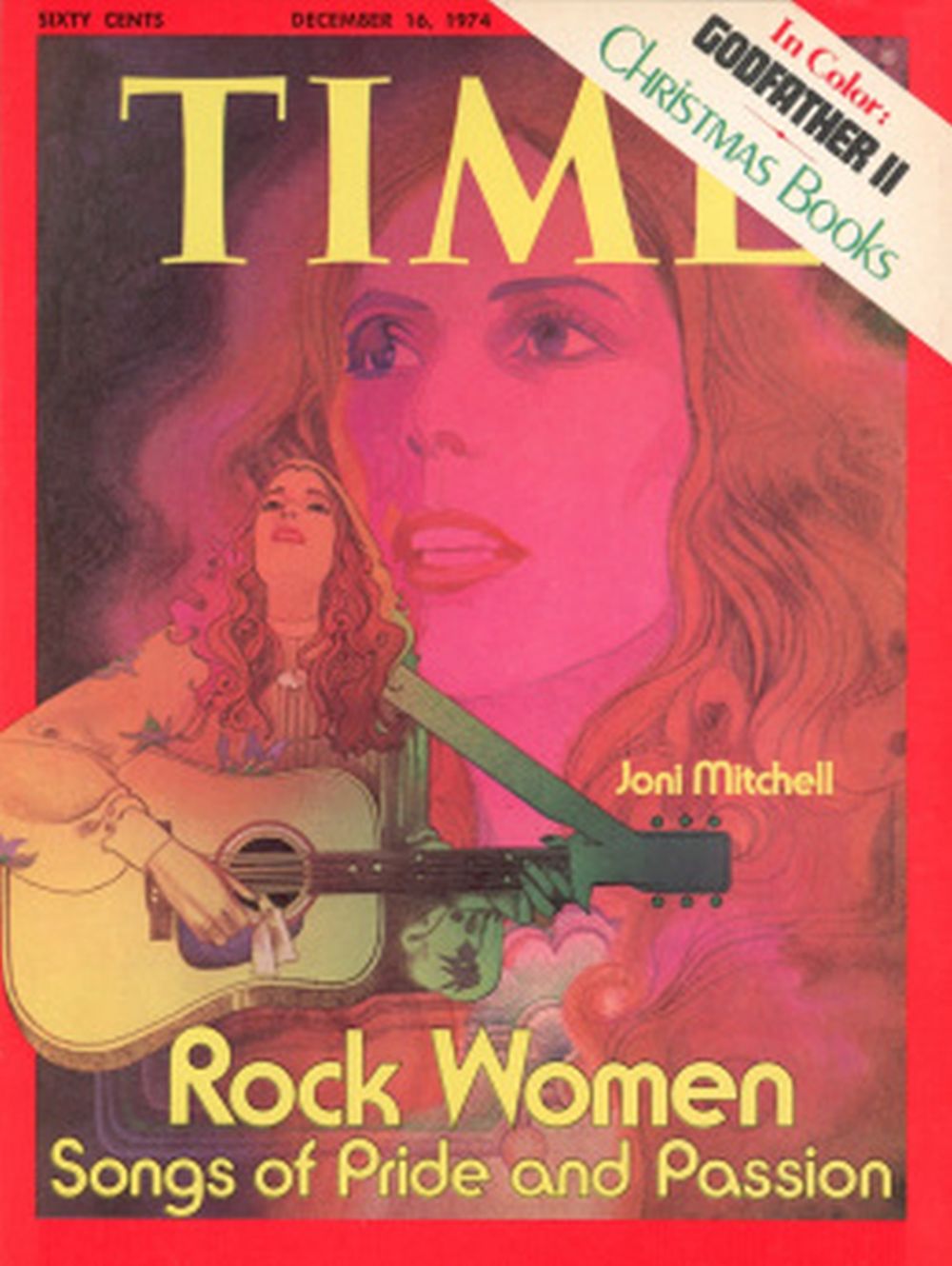

December 16, 1974 issue of Time magazine

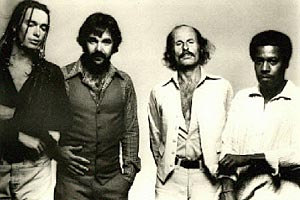

Joni onstage with Tom Scott 1974

‘Miles of Aisles’ eventually peaked at number 2 on the US charts. The cover of the December 16, 1974 issue of Time magazine is a brightly colored illustration of two different images of Joni Mitchell created by illustrator Bob Peak The illustration in the lower left corner shows Joni holding her guitar, head slightly tilted back with her long, luxuriant hair flowing in waves down over her shoulders. The illustration that appears behind this one and takes up most of magazine's cover is of Joni's face, mouth open, teeth in view, obviously singing with her hair once again framing her distinctive features. Joni's name appears in yellow lettering above the fretboard of her guitar. At the bottom, in large yellow lettering are the words 'Rock Women' with 'Songs of Pride and Passion' in smaller yellow letters beneath. The entire image is mostly colored in bright 1970s orange, pink and yellow. The magazine contains an article titled 'Rock and Roll's Leading Lady' which declares that Joni “is a creative force of unrivaled stature in the mercurial world of rock.” Joni Mitchell was enjoying a higher level of success in the music business than she had ever attained. In 1974 she purchased a house in the upscale Bel Air section of Los Angeles and moved into it with L.A. Express drummer John Guerin. Their romantic relationship had become increasingly evident during the months they had toured together. It would prove to be an important relationship for Joni on both a personal and a professional level.

In the spring of 1975 Joni recorded a collection of demos of new material. She played guitar, piano and synthesizer on these tapes, augmenting the music on some cuts with overdubs of her own voice. Most of the songs she recorded would appear on her next album. A few months after cutting the demo tapes, Joni went into the studio to record her seventh studio album. The resulting collection of songs was given the singular title ‘The Hissing of Summer Lawns’.

1975 National Geographic photo

From Norman Seeff's photo shoot for inside of 'The Hissing of Summer Lawn's' album cover

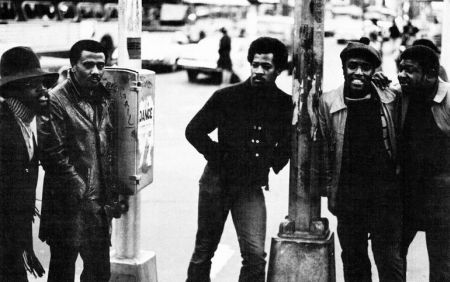

With the exception of Tom Scott, the musicians that had made up the L A Express all played in various combinations on most of the songs recorded for ‘The Hissing of Summer Lawns’. Both Larry Carlton and Robben Ford contributed and on one cut, Larry played electric guitar while Robben played dobro. Tom Scott’s horn playing was replaced by Chuck Findlay while Bud Shank played saxophone and flute. Max Bennett was bassist on the majority of the the tracks. Wilton Felder played bass on two songs. The record also features vocal backing from Joni’s faithful standbys, David Crosby, Graham Nash and James Taylor on the album’s opener and James plays guitar on the title song. There are also keyboard and percussion parts played by Victor Feldman on various cuts and a string arrangement by Dale Oehler for one song.

Whether it was because of the absence of Tom Scott, the influence of John Guerin, the musical choices of the players, Joni Mitchell pursuing a new musical vision or some combination of these elements, the sound of ‘The Hissing of Summer Lawns’ is distinctly different from that of ‘Court and Spark’. Joni’s demo tapes were somehow leaked and copies have made their way to members of her fan base. The songs recorded on these demos reveal that their arrangements on the finished album had already been mostly sketched out by Joni playing guitar and keyboards and using her voice to fill in the harmonic shadings of the additional instrumentation. Joni’s guitar playing on the song ‘Harry’s House’ is especially impressive on the demo. It is the only instrument she uses and it seems to contain most of the musical structure that is heard on the finished track. However, both Joni and Max Bennett have said that the recording sessions were looser and that the musicians were given more freedom to improvise. The chord structures and melodies combined with the shadings provided by the horns, percussion and keyboards move ‘The Hissing of Summer Lawns’ away from the pop idiom and further in the direction of jazz. Lyrically, there is also a shift away from the first person, confessional mode heard on ‘Court and Spark’ to a more observational tone and, in some songs, echoes of social criticism. The words to some of the songs are more akin to poetry than song lyrics. The careful choice and construction of words and phases create a compact, condensed language that teases the brain with multiple possibilities of interpretation. Up to this point, the lyrics of Joni’s recorded output had always been literate and exceptionally well crafted. For the most part, the words to her songs were fairly straightforward and direct in their description and storytelling. Some of the material on ‘The Hissing of Summer Lawns’ has a cryptic bent to it and uses metaphor and symbolic imagery in ways that far surpass anything Joni had put on record before.

Nonesuch Records 1974 'Burundi: Music From the Heart of Africa'

Anima rising

Wash my guilt of Eden

Wash and balance me

.....................................

Truth goes up in vapors

Steeples lean

Winds of change patriarchs

Snug in your Bible-belt dreams

God goes up the chimney

Like childhood Santa Claus

The good slaves love the Good Book

A rebel loves a cause

The song is a marked departure from any song about romantic relationships that Joni had previously recorded. There are also three songs that have a philosophical bent on ‘The Hissing of Summer Lawns’. The hauntingly beautiful ‘Sweet Bird’ is a dreamy sounding rumination on aging and the passage of time. The image of ‘the earth spinning and the sky forever rushing’ from ‘Sweet Bird’ has a frenetic, disorienting quality to it, a characteristic that is not so evident in the revolutions of ‘the carousel of time’ that Joni had written about in ‘The Circle Game’ nine years before. The title of the ‘The Boho Dance’ and its thematic content are borrowed from Tom Wolfe’s 1975 diatribe against the elitist world of Modern Art, ‘The Painted Word’. Joni transplants Wolfe’s view of Modernist painters as being disdainful of popular opinion and material success to the music world. She likens those who foreswear any desire for the adulation and wealth of stardom to ‘a priest with a pornographic watch looking and longing on the sly’ and answers criticism of her own success with the conclusion: ‘Nothing is capsulized in me on either side of town. The streets were never really mine, not mine these glamor gowns.’ The last cut of the record is ‘Shadows and Light’. Joni played an Arp Farfisa sythensizer and created the sound of a choir from overdubs of her own voice that give the song the sound of a church service anthem. The song is made up of three verses, each with a series of images that illustrate three contrasting concepts. The ‘ever-present laws’ that govern blindness and sight are ascribed to the Devil, the ‘everlasting laws’ that govern day and night are God’s while the ‘ever-broken laws’ of wrong and right are Man’s.

The enormous success of ‘Court and Spark’ had generated a high level of anticipation for its follow-up. It also raised the level of expectation. Joni had been given carte blanche for the creation of ‘The Hissing of Summer Lawns’ from the production of the record to the added expense of the embossing on the album’s cover. Asylum records was looking for another multimillion seller. Music critics were watching for something that would at least equal the exquisite design of ‘Court and Spark’. The public who had embraced Joni Mitchell’s music were expecting another collection of personalized songs that would again tap into the emotional context of their own lives.

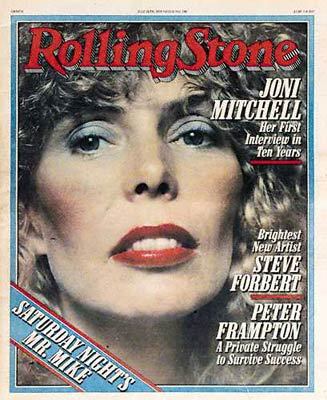

What they got was a record that was difficult for any of them to wrap their heads around. Asylum did get decent sales figures as ‘The Hissing of Summer Lawns’, perhaps propelled by the momentum generated by ‘Court and Spark’ and ‘Miles of Aisles’, went to number four on the Billboard Album charts. The critics and the fans got something that was either misunderstood or did not meet the expectation of what they felt a Joni Mitchell album was supposed to be. Both the intimacy and the lovably eccentric melodies that pushed her voice to the extremes of its remarkable range seemed to be missing. Reviews of the album were mixed. Rolling Stone’s take included the crass remark "Shadows and Light" suffers from too many vocal overdubs and a synthesizer that sounds like a long, solemn fart.’ The publication later jokingly referred to the record’s name as the worst album title of the year. Some of the people who bought the record were sufficiently intrigued to delve into its complexities and over the years ‘The Hissing of Summer Lawns’ has earned the respect it truly merits as a work that transcends the pop idiom and defies categorization. From the release of ‘The Hissing of Summer Lawns’ and beyond, labels would become increasingly difficult to pin on Joni Mitchell’s music.

Around

the same time that ‘The Hissing of Summer Lawns’ was

released, Bob Dylan had put together a conglomeration of musicians

that he named ‘The Rolling Thunder Revue’. The acts he

assembled went on an extensive road tour near the close of 1975.

Joan Baez, who had been involved in a love affair with Bob Dylan and

had also championed him as a performer in the beginning of his

career, frequently bringing him onstage at her own concerts, was one

of the featured performers in Rolling Thunder. After Dylan’s

distancing himself from Baez professionally and the subsequent

breakup of their romance, the two had not performed on the same stage

together in nearly ten years. Their professional reunion generated a

lot of publicity. Dylan employed a number of the musicians that had

played on his soon to be released 1976 album ‘Desire’ and

the performers in his revue included Roger McGuinn, Ramblin’

Jack Eliott, T-Bone Burnett, actress and singer Ronee Blakley and

Beat poet Allen Ginsberg. Joni joined up with Rolling Thunder in

November, performing in a series of concerts with the troupe in the

northeastern United States and Canada. On December 8th, she joined

Richie Havens, Roberta Flack and Robbie Robertson for a concert at

Madison Square Garden to benefit Rubin ‘Hurricane’

Carter, a former boxer who had been convicted and imprisoned for

murdering three people in a bar in Paterson, New York in 1966.

Carter published a book about his ordeal in 1974. He sent a copy of

his book to Bob Dylan who went to meet Carter in prison. Two

witnesses that had been instrumental in Carter’s conviction

ended up recanting their testimony and stated that they had been

bribed by authorities with money and leniency to implicate Rubin

Carter. Dylan subsequently wrote the song ‘Hurricane’

which appeared on his ‘Desire’ album and began a campaign

to right what he saw as a gross miscarriage of justice. Joni

canceled a benefit she had scheduled in California in order to appear

in ‘The Night of the Hurricane’, a concert that played to

the Madison Square Garden audience for more than four hours.

Around

the same time that ‘The Hissing of Summer Lawns’ was

released, Bob Dylan had put together a conglomeration of musicians

that he named ‘The Rolling Thunder Revue’. The acts he

assembled went on an extensive road tour near the close of 1975.

Joan Baez, who had been involved in a love affair with Bob Dylan and

had also championed him as a performer in the beginning of his

career, frequently bringing him onstage at her own concerts, was one

of the featured performers in Rolling Thunder. After Dylan’s

distancing himself from Baez professionally and the subsequent

breakup of their romance, the two had not performed on the same stage

together in nearly ten years. Their professional reunion generated a

lot of publicity. Dylan employed a number of the musicians that had

played on his soon to be released 1976 album ‘Desire’ and

the performers in his revue included Roger McGuinn, Ramblin’

Jack Eliott, T-Bone Burnett, actress and singer Ronee Blakley and

Beat poet Allen Ginsberg. Joni joined up with Rolling Thunder in

November, performing in a series of concerts with the troupe in the

northeastern United States and Canada. On December 8th, she joined

Richie Havens, Roberta Flack and Robbie Robertson for a concert at

Madison Square Garden to benefit Rubin ‘Hurricane’

Carter, a former boxer who had been convicted and imprisoned for

murdering three people in a bar in Paterson, New York in 1966.

Carter published a book about his ordeal in 1974. He sent a copy of

his book to Bob Dylan who went to meet Carter in prison. Two

witnesses that had been instrumental in Carter’s conviction

ended up recanting their testimony and stated that they had been

bribed by authorities with money and leniency to implicate Rubin

Carter. Dylan subsequently wrote the song ‘Hurricane’

which appeared on his ‘Desire’ album and began a campaign

to right what he saw as a gross miscarriage of justice. Joni

canceled a benefit she had scheduled in California in order to appear

in ‘The Night of the Hurricane’, a concert that played to

the Madison Square Garden audience for more than four hours.

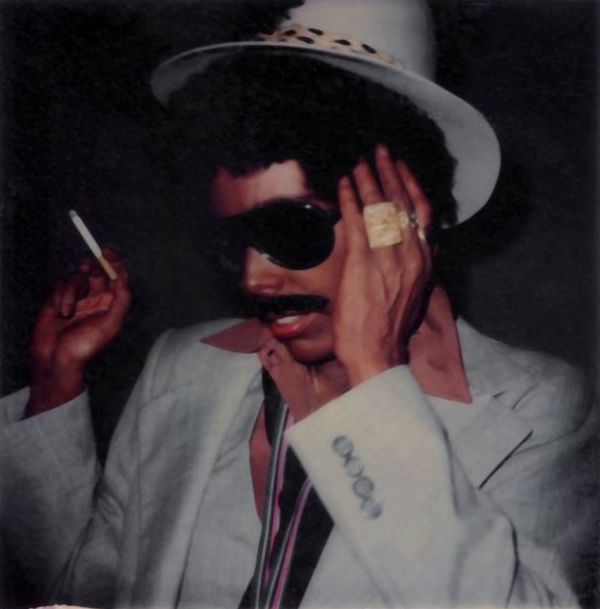

Joni onstage with cigarette 1976

This tour was originally planned as a world tour. The January 24, 1976 issue of Melody Maker reported that Joni and the L.A. Express would appear in Japan and Australia during April and early May and then begin a tour of Europe, beginning with a stop in Oslo Norway on May 14th. The first U.S. Stop on the tour was in Minneapolis at the University of Minnesota’s Northrup Auditorium followed by a concert at Purdue University in West Lafayette Indiana where Neil Young showed up onstage for Joni’s encore. The description given by one attendee of this concert in the website Chronology says that Neil walked onto a darkened stage and began to perform his song ‘Helpless’. He was greeted by wild enthusiasm from the audience and midway through the song, Joni came on stage to sing with him. The two performed ‘Sugar Mountain’ together and then Joni told the story of how she came to write ‘The Circle Game’ as her response to that song. The concert ended with Joni & Neil performing ‘The Circle Game’ as a memorable duet. The next leg of the tour swung down to St. Louis, then to Houston. Joni performed in the Houston Astrodome on January 25th as part of Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue for ‘Night of the Hurricane II’, another benefit for Rubin Carter. Dylan made a surprise guest appearance at Joni’s concert on the 28th at the Municipal Auditorium in Austin. The pair duet-ted on ‘Both Sides Now’ and Dylan performed ‘Girl From the North Country’.

Judging by the some of the reviews of various concerts, the overall vibe was not as felicitous during this tour as it had been for Joni Mitchell’s previous outings with the L.A. Express. Some reviewers described Joni’s demeanor as being removed and distant from her audiences and one or two mention that the crowds were not as quietly attentive as those that Max Bennett described for her 1974 concerts with the LA Express. There are reports of Joni playing with her back to the audience in some concerts, inviting comparison to one of her idols, Miles Davis. A review in the Daily Cougar of the show at Houston’s Sam Houston Coliseum gives an account of a disgruntled Joni telling a restless audience "I guess you people want to boogie, don't you? ...Well we're gonna cut out half the show." The reviewer then goes on to say “After settling down a bit, Mitchell explained how difficult it is to sing softly with so much "turmoil" going on in the audience.” After singing one song at the University of Maryland’s Cole Fieldhouse in College Park, Maryland, Joni left the stage and was reportedly too ill with flu to perform any more. Nevertheless, she took the stage the next night in New Haven, Connecticut and performed an entire concert. The tour ended rather abruptly on February 29th with a show in Madison Wisconsin at the Dane County Coliseum. Melody Maker's March 20, 1976 issue carried a short piece stating that Joni Mitchell's European tour had been canceled due to Joni's state of extreme exhaustion. The article went on to say that doctors had 'ordered her to rest for five months.'

From my own experience of attending rock concerts during the mid 1970s in large arena type venues, I can’t say that I remember an audience that kept quiet and entirely attentive during any of the performances I saw. Maybe the nature of audiences changed as the Me Decade got into full swing from what it had been in an earlier time. Alcohol consumption and drugs or the different types of drugs that were consumed probably played a part in this change. I remember that the music at most of those concerts was so loud that no-one would have known if the audiences were making noise or not while the musicians sang and played. It is clear that Joni Mitchell’s fan base had been accustomed to performances of material that was of an intimate, personal nature delivered by an artist who was emotionally engaged in communicating that material. That type of performance had set up a different kind of relationship between the performer and her audience from the one that seems to have developed during at least some of the concerts on this tour. As she grew older and the circumstances of her life changed, the observational nature of her writing made it inevitable that Joni’s songs would also change. Experience had wrought a shift in her point of view. Much of the innocence had dropped away and more mature, darker, sometimes even cynical tones had begun to emerge. Joni Mitchell was no longer the only musician onstage during her concerts and her song writing had evolved. However the music she was performing was not hard-core, full tilt boogie, rock and roll blasted at high volumes, either. I suspect that there was some difference in the expectations of both the audience and the performer from what actually transpired during Joni’s tour in January and February of 1976.

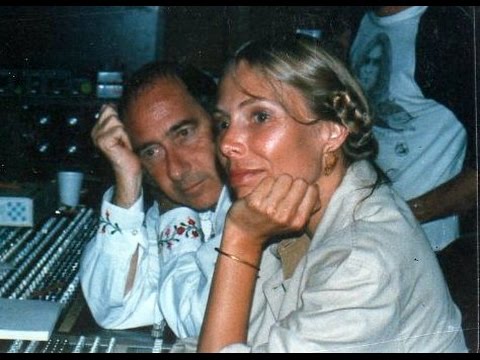

John Guerin & Joni Mitchell

Joni joined ‘Rolling Thunder’ again in May of 1976 for two shows in Texas. Joni has said that cocaine usage was rampant in the Rolling Thunder company and that she herself was using the drug during the time that she performed with the revue. She credits an encounter with the Tibetan Buddhist master Chögyam Trungpa with helping her break free of her dependence on the drug. Finding herself back in Los Angeles after her last two appearances with Rolling Thunder and faced with the aftermath of her break up with John Guerin, Joni was feeling at loose ends. She was sitting at the beach at Neil Young’s house when two friends showed up who told her they were leaving on a road trip that would take them across the U.S. to New England. This seemed like an ideal opportunity for Joni to distance herself from the disarray her life had fallen into and she immediately decided to go with them.

The threesome drove from Los Angeles to Maine. When they reached the state of Maine, Joni departed solo and began a journey all on her own. She drove down the east coast, across the southern part of the U.S. and finally back to California. She has said that she did not have a driver’s license with her at this time. She followed the trucks on the roads as much as possible, knowing that the drivers kept tabs on the whereabouts of the police via their CB radios and would send out signals when any law enforcement vehicles were nearby. As she made her way across the south, she discovered that she was not much recognized in this part of the country and began to enjoy the freedom that her anonymity allowed her. She was able to meet and form relationships with people who had no knowledge or preconceived notions about who she was. As a human being, this must have been a liberating experience for Joni, to be able to connect with other humans who knew nothing of the specific milieu she inhabited in the music business and brought no expectations to their interactions with her. As a writer it was also an ideal opportunity to observe this broader world that the majority of Americans inhabited. Her perspective had gone out of synch with the world at large. As she traveled through and interacted with that larger sphere of existence, she began to regain her emotional balance. The whole experience became both a spiritual and a creative journey for Joni Mitchell. Eventually it contributed a large part to one of her most significant musical creations.

Joni’s encounters and experiences on the road provided a multitude of story lines to choose from for lyrical content and new songs emerged as she traveled. In the summer of 1976 she recorded two of the songs she had introduced on her winter tour and seven new ones, mostly written on her solitary road trip, that would become the album ‘Hejira’.

The word ‘Hejira’ derives from the Islamic faith. It is the the name given to the prophet Muhammad’s flight from Mecca to Medina when he learned he was the target of an assassination plot. Joni chose the word as a title because she felt it represented her abrupt departure from L.A. as a ‘running away with honor’. Most of the songs are about traveling or about people met and incidents that occurred during a journey. The music is entirely guitar based, in keeping with the theme of solitary travel by automobile. The lyrical lines tend to be long, emulating the long stretches of highway that a car rolls along over the course of an extended road trip. Joni describes both the external scenarios and the corresponding internal landscapes that reveal themselves along the way. Her genius for literary visualization is at its height in the songs that make up ‘Hejira’, a record that many fans and critics consider to be the peak of her musical career.

The first track of ‘Hejira’ sets the tone of travel, exploration and self examination. ‘Coyote’ is one of the songs Joni introduced in her concerts at the beginning of 1976. She assumes the role of a hitchhiker in this song who catches a ride with the title character. Joni contrasts the life Coyote lives on his ranch with the world of ‘air conditioned cubicles’ that she inhabits in Los Angeles. He is ‘brushing out a brood mare’s tail while the sun is ascending’ while she is just ‘getting home with my reel-to-reel’. There is a wild streak in him that will not be tamed and a sexual appetite that he feeds at will.

And the next thing I

know

That coyote's at my door

He pins me in a corner and he

won't take no

He drags me out on the dance floor

And we're

dancing close and slow

Now he's got a woman at home

He's got

another woman down the hall

He seems to want me anyway

Furry Lewis

But Joni does not see any deliberate intent to inflict harm in Coyote’s motivations saying that he is ‘not a hit and run driver....racing away’. He is merely following the dictates of his nature as she is following her own instincts, declaring that he ‘just picked up a hitcher, a prisoner of the white lines on the freeway’. Some have suggested that those white lines refer to lines of white cocaine. Certainly, as she breaks down the word freeway into ‘free free-way’ at the end of the song, there is an ironic bent to the line. She has ‘tried to run away myself, to run away and wrestle with my ego’ but the escape has made her a ‘prisoner of the fine white lines’ of that ‘free freeway’. There is perhaps room for an underlying double entendre here. The ‘prisoner’ could be addicted to a drug. It seems more likely that the word refers to the singer’s inability to break out of her ego’s inescapable need for autonomy and the need to forge ahead on that 'free freeway' of artistic and self discovery. Another sexual encounter brings out different thoughts and feelings as the singer describes ‘A Strange Boy’. This time the male partner has the attitude of a Peter Pan. ‘He still lives with his family, even the war and the Navy couldn’t bring him to maturity.’ Nevertheless, she recognizes a special quality in the perceptions of this man who weaves ‘a course of grace and havoc’ on a skateboard. He ‘sees the cars as sets of waves, sequences of mass and space’ and also ‘sees the damage in my face’. Harkening back to the song ‘A Case of You’, she likens love to inebriation, singing ‘we got high on travel and we got drunk on alcohol, and on love the strongest poison and medicine of all’. In spite of her frustration with the Strange Boy’s refusal to grow up, she admits ‘I gave him my warm body, I gave him power over me’. The other song on ‘Hejira’ that Joni had written before her road trip and had first performed on tour with the L.A. Express is ‘Furry Sings the Blues’. This is a song that is drawn from an experience that Joni has described in several interviews over the years. During the 1976 winter tour, Joni and the L.A. Express had played a show in Memphis, Tennessee. The day after the concert, Joni made a visit to Furry Lewis, a blues guitarist who had played with W. C. Handy and had once been a part of the jazz and blues music scene that was centered around Memphis’s Beale Street. Furry lived near Beale Street at the time Joni went to see him and was close to 83 years old. A photo of his grave marker gives the date of his birth as March 8, 1893. Just a few years later, the efforts of the Beale Street Development Corporation would succeed in saving the historic home of the ‘Memphis Blues’, but at the time Joni saw it, Beale Street had fallen into a state of urban decay with many of its historic buildings boarded up ‘waiting for the wrecker’s beat’. Joni paints a picture of decline tempered with pathos. Furry Lewis is ‘propped up in his bed with his dentures and his leg removed’ while outside ‘old Beale Street is coming down....faded out with ragtime blues’. When he performs, Joni hears it as ‘mostly muttering now and sideshow spiel’. But just as she can sense the vitality that once informed Beale Street, ‘Ghosts of the dark town society come right out of the bricks at me...in their finery dancing it up and making deals’, she catches a glimpse of the performing artist that Furry once was in ‘one song he played that I could really feel’. Before leaving, Joni mentally addresses the statue of W. C. Handy that stands on Beale Street, ‘W. C. Handy, I’m rich and I’m fey’ and thinking about Furry Lewis she ponders ‘Why should I expect that old guy to give it to me true? When he’s fallen to hard luck and time and other thieves, while our limo is shining on his shanty street’. In a pair of interviews that Joni participated in during a celebration in honor of her 70th birthday at Toronto’s Luminato festival in June of 2013, Joni was asked to name one of her creations that she was especially proud of. In both interviews she cited the following lines from ‘Furry Sings the Blues’ as an example of something that had particularly excited her at the time of their creation:

Pawn shops glitter

like gold tooth caps

In the grey decay

They chew the last few

dollars off

Old Beale Street's carcass

Carrion and mercy

Blue

and silver sparkling drums

Cheap guitars eye shades and guns

Aimed

at the hot blood of being no one

Down and out in Memphis

Tennessee

Old Furry sings the blues

The title track of ‘Hejira’ has the steady, repetitive rhythm of rolling wheels and passing scenery as a car threads its way over mile after mile of highway. As Joni’s guitar pickings drive the song’s momentum, the words spin threads of description coupled with reflective thoughts and emotions about her travels and state of mind. She pictures herself as ‘a defector from the petty wars that shell-shock love away’. The lyrics are extraordinary in the aptness and originality of their imagery coupled with the depth and richness of their observations. The song is full of intensely personal observations that are also remarkable in their universality. It is difficult to pick out even a few lines that convey the scope and brilliance of this piece of music. In the ‘comfort of melancholy when there’s no need to explain’, a state of mind that Joni describes as ‘just as natural as the weather in this moody sky today’. Joni addresses her problematic love relationship ‘in our possessive coupling so much could not be expressed’ and the reason she left it ‘so now I am returning to myself these things that you and I suppressed’. She describes the isolated state of being human ‘I know no-one’s gonna show me everything we all come and go unknown, each so deep and superficial between the forceps and the stone’. From there her thoughts flow into an observation of the finite nature of life and her attempt to leave behind something that will endure after her death ‘Well I looked at the granite markers, those tributes to finality to Eternity and then I looked at myself here, chicken scratching for my immortality’. The flames and dripping wax of candles burning in a church become a metaphor for her dualistic view of life ‘In the church they light the candles, and the wax rolls down like tears, there is the hope and the hopelessness, I’ve witnessed thirty years’. She is able to glimpse a view of human life as ‘only particles of change orbiting around the sun’ but wonders how she can sustain that concept of isolated, ever changing individuality ‘when I’m always bound and tied to someone?’. Finally she acknowledges that her need for connection and love will ultimately force her out of her isolation. She is only a ‘defector from the petty wars until love sucks me back that way’. ‘Song for Sharon’ is a long open letter to Joni’s childhood friend Sharon Bell Veer. What seems to be a long, rambling rumination is actually a linear train of thought that explains the persistent remnants of Joni’s obsession with the romantic cultural notions of a committed relationship. She describes how ‘when we were kids in Maidstone Sharon, I went to every wedding in that little town’ and afterward ‘walking home on the railroad tracks or swinging on the playground swing, love stimulated my illusions more than anything’. Even after experiencing the hurt and disappointment ‘first you get the kisses and then you get the tears’ she admits that ‘the ceremony of the bells and lace still veils this reckless fool here’. The song begins with Joni describing a trip to Staten Island to buy a mandolin where she sees ‘the long white dress of love on a store front mannequin’ and in the last verse she describes how Sharon has ‘a husband and a family and a farm, I’ve got the apple of temptation and a diamond snake around my arm’. In a phone interview conducted by Debi Martin and published on JoniMitchell.com in 1983, Joni explained ‘But what it was was when we were kids, she (Sharon Bell Veer) was going to marry - she was into voice lessons and, you know, performed in adjudicated classical competitions, right? She was the singer. And I liked to be out in the country so I was going to marry a farmer and she was going to be a famous singer. And it was just so peculiar that fate had these childhood fantasies reversed.’ In the song ‘Amelia’ Joni seems to be seeing the futility of her romantic illusions as she addresses the iconic aviator Amelia Earhart. Amelia’s famous disappearance near Howland Island in the Pacific Ocean while attempting a round the world flight in 1937 have made her ‘a ghost of aviation’ who was ‘swallowed by the sky or by the sea’. Joni describes her own travels, her love relationship, her ‘dream to fly’, and ends each verse by telling ‘Amelia it was just a false alarm’. She questions her ability to love and sees how she has ‘spent my whole life in clouds at icy altitudes’. This lofty, isolated state of mind became overwhelming when ‘looking down on everything I crashed into his arms’. The frenetic rhythm and lyrics of ‘Black Crow’ describe a predilection for ‘diving down to pick up on every shiny thing just like that black crow flying in a blue sky’. In this song Joni has been ‘traveling so long’ and wonders ‘how’m I ever going to know my home when I see it again’. In contrast the mood is languid in the appropriately named ‘Blue Motel Room’. Mid-way through her long journey in a ‘blue motel room with a blue bedspread’ in Savannah, Georgia, Joni’s ‘got the blues inside and outside my head’. There seem to be second thoughts about the break from her lover and she wonders ‘will you still love me when I get back to town?’ The final track of the album ‘Refuge of the Roads’ is Joni’s summing up of her ‘Hejira’. Muhammad may have traveled from Mecca to seek a refuge in the city of Medina but in Joni Mitchell's case, the travel itself became the refuge she sought. She begins with her meeting with Chögyam Trungpa and his prescription for her psychological and spiritual ailments:

I met a friend of

spirit

He drank and womanized

And I sat before his sanity

I

was holding back from crying

He saw my complications

And he

mirrored me back simplified

And we laughed how our

perfection

Would always be denied

"Heart and humor and

humility"

He said "Will lighten up your heavy load"

I

left him for the refuge of the roads

She meets a band of ‘drifters cast up on a beach town’, and sings that she ‘wound up fixing dinner for them and Boston Jim’. There is a sense of simple enjoyment of ‘spring along the ditches’ and ‘good times in the cities’ that Joni expresses as ‘radiant happiness...all so light and easy’. But eventually she realizes that the never-ending holiday spirit of this kind of life is not enough to sustain her. As she ‘started analyzing...a thunderhead of judgment was gathering in my gaze’. There is a perceptible downside to ‘what I was seeing in the refuge of the roads’. The last verse of the song finds her ‘in a highway service station’, looking at ‘a photograph of the earth taken coming back from the moon’. As she contemplates this view of the earth from the remote height of outer space she makes the humbling observation ‘you couldn’t see a city on that marbled bowling ball or a forest or a highway or me here least of all’. Although she is still ‘seeking refuge in the roads’ her ‘baggage overload’ is ‘westbound and rolling’ and will eventually return to Los Angeles. She was a prisoner of the white lines on the free, freeway when she hitched a ride at the beginning of her journey. But now she views the road not as an obsession or an addiction she feels inescapably compelled to follow. The roads she traveled became a much needed refuge where she could find the prescribed ‘heart and humor and humility’. Still with a 'baggage overload' but refreshed and with a restored balance, she is heading west, back to L.A. to continue her life's journey on the path she has chosen to follow.

Although the artwork for ‘Hejira’s original cardboard album cover does not display any of Joni Mitchell’s paintings, the credits show that she designed the cover and the combination of black and white photographs that appear are beautifully executed and carefully chosen to illustrate elements of the record’s lyrical content. The photo on the front of the gatefold shows Joni from the waist up, draped in a dark fur coat. The coat has another image superimposed on it of a straight stretch of highway that tapers toward a horizon capped by white clouds. Her right elbow is bent upward and the hand holds a lit cigarette. The left hand is tucked into a pocket. A beret sits on top of Joni’s head, slanting across her forehead from the top of her head on her right and covering most of the eyebrow on the left of her face. Her straight blonde hair is swept around the back of her head and flying out to her right as if blown by a strong wind. She gazes directly and unflinchingly into the camera. The lighting sets off Joni’s fine cheekbones and the slight protrusion of the lower lip gives the otherwise expressionless face a sensual quality. She is standing in front of a backdrop of a large expanse of frozen water with a bank of ice and snow laden trees in the cover’s upper right corner. ‘Joni Mitchell Hejira’ appears in a simple but elegant looking type in the center at the top. The back of the cover is taken up by a picture of a frozen lake. The Olympic ice skater Toller Cranston is on the ice in the middle distance on the left. He is dressed in a sequin accented performance costume, crouching on the ice with his body bent toward the right and his arms reaching toward the figure of a woman in a bridal gown and veil standing at a distance behind him with her hands clasped in front of her. The track list, in the same type as the album’s title on the front, is directly under Cranston’s skates. The frozen lake takes up the entire spread of the inside of the gatefold. The left side has a photo of Joni vigorously skating across the ice. Her arms are outstretched and she is turned away from the camera, displaying a fur cape with tassels hanging from it that suggest black feathers. The lyrics and album credits are printed over the remaining three quarters of the inside of the jacket. The sleeve that the vinyl lp fits into also has a beautiful, semi-glossy black and white photo. This is a shot of Joni from the front, wearing the tasseled cape and a cloche style cap that is covered in black feathers. Her arms are once again stretched out to her sides and suggest bird’s wings. There are dark clouds behind her in this picture. The horizon is at the bottom of the shot and the view below the clouds is completely dark and featureless. Joni’s lips are slightly parted and there is a dreamy, almost beatific look on her face. The image with the clouds behind Joni’s head and her draped arms outstretched like wings gives the impression that she is flying somewhere above the dark ground below her. According to an article from Rock Photo’s June 1985 issue, the cover design is actually a composite of 14 different photos that Joni used an instrument called a Camera Lucida to re-size and piece together. The photo of Joni skating was taken by Joel Bernstein on Lake Mendota in Wisconsin when Joni had performed the last date of her 1976 tour at Madison’s Dane County Coliseum. Toller Cranston and the bride were photographed in a hockey arena. Norman Seeff took the photo of Joni that appears on the cover. Careful airbrushing helped smooth out the edges of the pieced together images that Joni took a single negative of to create one master shot.

Joni skating on Lake Mendota in 1976 photographed by Joel Bernstein

‘Hejira’ was released in November of 1976 to mostly positive reviews. Many critics referred to the album as a ‘return to form’, which probably meant that Joni had gone back to more of the ‘confessional’ style in her lyrics and a more bare bones guitar based sound. Although it did not sell as well as ‘Court and Spark’ and ‘The Hissing of Summer Lawns’, ‘Hejira’ peaked at 13 on Billboard’s 200 pop album chart and became a certified Gold album. A single of ‘Coyote’ b/w ‘Blue Motel Room’ was released but it failed to register on any of the record sales charts. Like much of Joni Mitchell’s post ‘Court and Spark’ output, ‘Hejira’s reputation has gained considerable ground in the intervening years and is now considered by many to be a uniquely innovative, classic piece of musical art. Joni has said that she believes nobody but herself could have created it.

Two days before the release of 'Hejira' on November 20, 1976, Joni Mitchell appeared with Jaco Pastorius and percussionist Bobbye Hall at Memorial Auditorium in Sacramento for a Save the Whales benefit concert titled 'California Celebrates the Whales'. The trio performed a set that was made up mostly of songs from 'Hejira' and 'The Hissing of Summer Lawns'. A bootleg recording of this concert has been in circulation for years and is now posted on YouTube. A highlight is a jazzy, laid back rendition of 'Shadows and Light'. The song 'Jericho' that was featured on the 'Miles of Aisles' album is also performed with an extended bass solo from Jaco added to the end. There is obviously a musical chemistry between the two performers as Joni's guitar and Jaco's bass play off one another throughout the set. Joni does play solo accompaniment on 'Song For Sharon', making the addition 'and the whales' to the lyric 'help the needy and the crippled'. The finale is a song called 'Dolphins' by Fred Neill with Joni singing harmony and backup vocal.

Joni & Neil Young - The Last Waltz, November 1976

Joni was nominated for a Grammy award for Best Female Pop Vocal performance of 1976. The ceremony was held in February of 1977 with Linda Rondstadt winning the award for her album ‘Hasten Down the Wind’. Joni was scheduled to go on tour in the summer of 1977 but the tour had to be canceled when Joni was hospitalized for a month with abscessed ovaries. The experience could have been the beginning of an aversion to modern western medicine that persisted for many years. This battle with a serious health problem also prompted Joni to turn back to her first medium of artistic expression. In the catalog for an exhibition of her paintings in 2000 at the Mendel Art Gallery in Saskatoon she wrote, "In the early '70s, I was given a camera by (singer) Graham Nash, a good camera -- a Leicaflex....After that I put down the sketchbook and photographed everything in sight -- even the cross fades in movies. I didn't paint again until 1977 when a serious illness put me in the hospital for about a month and predatory doctors threatened to take out some things that I really needed. In protest, I ordered art supplies to be sent to my hospital room and I painted a series of works I call The Delirium Paintings ... some of which I don't quite understand."

Mike Gibbs

Henry Lewy & Joni Mitchell

Upon completion, all the pieces of this remarkable sixteen minutes and nineteen seconds of music formed a cohesive whole that was given the title ‘Paprika Plains’. Joni had never attempted anything of this scope before and ‘Paprika Plains’ stands as perhaps the most ambitious and complex piece of her musical output. ‘Paprika Plains’ became one side of her next studio release, a double vinyl LP called ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’.

Up until the mid 1960s, the release of album packages that contained two vinyl LPs was a practice of record labels that was usually reserved for classical music or for particularly prestigious popular artists. The format was often used for recordings of live performances. With the release of Bob Dylan’s ‘Blonde on Blonde’ in 1966 and the Beatles’ ‘White Album’ in 1968, the double album became a vehicle for top selling artists in pop music to broaden the range of the music they could put into one new release. The 1970s saw a number of two record releases from music industry heavy hitters. Stevie Wonder released the double album ‘Songs in the Key of Life’ in 1976 which is considered to be one of his finest achievements. Elton John’s two record set ‘Goodbye Yellow Brick Road’ appeared in 1973 and became one of his best selling albums. Many artists used the double album format to stretch themselves and experiment with their music. Todd Rundgren’s ‘Something/Anything’ released in 1972 is considered to be a springboard for his exploration of progressive rock. Prog rock bands used the format to create extended tracks of music. Each of the fours sides of ‘Tales From Topographic Oceans’, the 1973 release from the progressive rock band Yes is comprised of one track of continuous music, each track clocking in at around twenty minutes in length. Fleetwood Mac, whose ‘Rumors’ album is one of the best-selling record albums of all time, followed that album up with the release of their double album ‘Tusk’ in 1979. ‘Tusk’ was a departure for Fleetwood Mac largely due to the experimental production techniques employed by Lindsey Buckingham.

According to the biography that Wally Breese, the original creator of JoniMitchell.com compiled, Joni’s contract with Asylum was close to its completion. In reference to ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’, Joni is quoted as saying "This record followed on the tail of persecution, it's experimental, and it didn't really matter what I did, I just had to fulfill my contract". The length of ‘Paprika Plains’ is somewhat shy of the usual length of one side of a vinyl LP. But it is hard to imagine a song preceding or following ‘Paprika Plains’. The flow of the music and lyrics from the piano intro to the piece’s coda comprises a stand-alone work. The only logical way to put this recording on an album was to give it one full side of an LP. It became the centerpiece of Joni’s ‘experimental’ record. Joni recorded two of the songs she had introduced on her tour with The L A Express in January and February of 1976. The title track of the new album, ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’ had been performed during the tour as a companion piece to ‘Coyote’. The other song first heard on the 1976 tour was ‘Talk To Me’. One of the songs that Joni had recorded on the demos she had made before ‘The Hissing of Summer Lawns’ sessions, ‘Dreamland’, was included and the song ‘Jericho’, first heard in performance during the ‘Miles of Aisles’ tour was given a more polished studio treatment. There were four more songs that Joni composed for ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’ plus a nearly seven minute percussion piece with a call and response vocal led by Puerto Rican born percussionist Manolo Badrena with Joni Mitchell, drummer Don Alias, singer Chaka Khan and Peruvian born percussionist Alejandro Acuna providing the chant like response parts. The resulting musical patchwork made up a total running time of slightly less than one hour. Putting this amount of recorded music onto two LPs was a bit of a stretch. However, the songs that make up the three sides that come before and after ‘Paprika Plains’ are grouped and sequenced so that each side almost tells a story. Lyrically, ‘Paprika Plains’ contains thematic elements and settings that are somewhat tangential to the rest of the songs on ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’.

The lyrics of ‘Paprika Plains’ begin with a description of a rainstorm as it hits a crowded bar. Joni gives a vivid sense of the atmosphere just by describing the combination of smells: ‘In the washroom women tracked the rain up to the makeup mirror, liquid soap and grass and Jungle Gardenia crash on Pine-Sol and beer’. The close atmosphere of the bar drives the singer outside to get some air where the rain evokes memories of childhood in a small prairie town where ‘sky-oriented people geared to changing weather’ ‘would have cleared the floor just to watch the rain come down’. She falls into a reverie as she’s ‘floating off in time’. Images of Canadian aboriginal people coming into one of the small towns Joni lived in as a young child emerge from her thoughts. She pictures these people ‘with their tasseled teams...all in their beaded leathers’ and describes how her young imagination was stimulated by their appearance: ‘I would tie on colored feathers and I’d beat the drum like war’. But ‘when the church got through, they traded their beads for bottles, smashed on Railway Avenue’. The alcohol exacerbates the despair and anger generated by long years of oppression. Divided from their heritage, ‘they cut off their braids and lost some link with nature’. The memories remove her further from the reality of the moment as Joni finds herself ‘floating into dreams’. Her dream state engenders a vision of ‘Paprika plains, vast and bleak and God forsaken, Paprika plains and a turquoise river snaking’. At this point the orchestrated piano interlude begins and there is no singing for the duration of this section of the track. However, inserted into the printed lyrics on the inside of the record’s gatefold jacket and enclosed in parentheses is a description of an extended dream sequence, written in verse as if intended as an unsung piece of the song. These Paprika plains are a dream-scape ‘far from the digits of business hours’ where ‘all time is stripped away’. They comprise a barren, desolate place with no ‘sprout or egg to measure loss or gain’. The only life to be seen is ‘a little band of Indian men‘ that the dreamer observes from a helicopter. One of these men ‘like a phoenix up from ashes...springs with a fist raised up to turquoise skies.’ The mushroom cloud of a bomb rises from the horizon and ‘to it like a golfer’s tee’ a giant pink and yellow beach ball appears. Joni dreams that the ball becomes ‘the blues and greens of earth from space probe photographs’. She floats out of the helicopter, ‘naked as infancy’ and falls against the ball to ‘suckle at my mother’s breast’ and ‘embrace my mother earth’. But, comparing herself to the biblical Eve who ‘succumbed to reckless curiosity’, she punctures the globe with her ‘sharpest fingernail’ and is once again left with a view of ‘vast Paprika plains and the snake the river traces and a little band of Indian men with no expressions on their faces’. As the instrumental section ends the sung lyrics pick up back at the bar where ‘the rain retreats like troops to fall on other fields and streets’. The singer walks back toward the dance floor where she spots the companion she is with ‘through the smoke with your eyes on fire from J&B and coke’. The band begins to play, the disco ball starts to ‘sputter lights and spin, dizzy on the dancers geared to changing rhythms’ and the lyrical part of ‘Paprika Plains’ concludes with ‘No matter what you do I’m floating back, I’m floating back to you’. There is the pause of a beat and then the piano pounds out the first chords of the musical tag which ends with Jaco Pastorius playing drawn out, bending electric bass notes over the sustained sounds of the orchestra’s string section.

Sequentially, ‘Paprika Plains’ was placed on the second side of the first of the two vinyl records that made up the original release of ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’. The opening track on the first side is an instrumental and choral ‘Overture’. Joni’s over-dubbed voice sings wordless close harmony phrasings over the interplay of her guitar and Jaco Pastorius’s multifaceted bass lines. The sounds produced spark the listener’s curiosity in a sonically engaging, seemingly random musical abstraction that finally settles into the first rhythmic chords that lead into the song ‘Cotton Avenue’. ‘Cotton Avenue’ is a celebration of a favorite dance spot that perhaps takes the listener to the bar described in ‘Paprika Plains’. There is a ‘summer storm brewing in the southern sky’ and the singer anticipates ‘dancing high and dry to rhythm and blues’ by the time it hits. The next song, ‘Talk To Me’ finds the singer desperately trying to entice a man she is attracted to into a conversation. She sings ‘I didn’t know I drank such a lot’ and laments ‘oh I talk too loose, again I talk too open and free’ while ‘Mr. Mystery’, the object of her interest ‘spends every sentence as if it was marked currency’. ‘Talk to Me’ is full of humor and clever turns of phrase pouring out of a mind that ‘picks up all these pictures’ and ‘can still get my feet up to dance even though it’s covered with keyloids from the slings and arrows of outrageous romance’, a line she admits she stole from ‘Willie the Shake’. The third and final song on the first quarter of ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’ is ‘Jericho’, the song that Joni introduced as a hopeful, new song on the live ‘Miles of Aisles’ album. The song is Joni’s ‘promise that I made to love when it was new’ to make an honest effort to stay open to a new romantic partner. She wants to find ‘the way to keep the good feelings alive’, engage in the ‘rich exchange’ of emotional support and shared time and ‘just like Jericho, let these walls come tumbling down’.

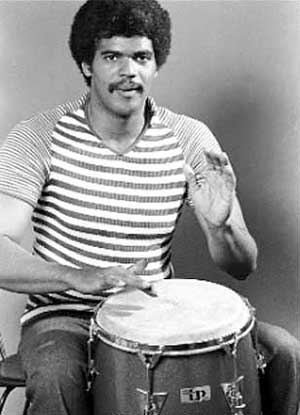

Don Alias

Joni has been quoted as saying about the album ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’: ‘Basically it has to do with turning your back on America and heading into the Third World.’ The three tracks on the third side of the record (first side of the second LP ) sketch out a progression, starting in Miami where Joni sets ‘Otis and Marlena’. Otis and Marlena are two snow bird vacationers from somewhere up north who have come to Miami ‘for fun and sun while Muslims stick up Washington’. This phrase is repeated at the end of all three verses of the song and is a reference to an incident from March of 1977 known as the Hanafi Siege. Twelve gunmen who were members of the Hanafi Movement, an organization that had split away from the Nation of Islam, took control of three buildings in Washington DC (the District Building or city hall, now called the John A. Wilson Building, B'nai B'rith headquarters, and the Islamic Center of Washington), held 149 people as hostages and killed one radio journalist. The repetition of the phrase in the song seems to be a commentary on the obliviousness of the mostly elderly people who flock to Florida in the winter months. Joni gives an acrimonious portrayal, describing the Miami Royal hotel that Otis and Marlena check into as ‘that celebrated dump’ and ‘her royal travesty’. She describes ‘fluorescent fossil yards’ where ‘freckled hands are shuffling cards’ and paints the scathing verbal image of ‘the grand parades of cellulite jiggling to her golden pools’. After the final ‘Muslims hold up Washington’ the music seems to slip into another dream state with percussion instruments percolating up, a few sustained piano chords played by Michel Colomber and Joni’s voice mixed into the background singing eerie sounding notes that resolve into the two words ‘dream on’. There is no break in the sound as the music forms a bridge into ‘The Tenth World’, a six minute and 45 second percussion interlude of congas played by American jazz percussionist Don Alias, Puerto Rican born percussionist Manolo Badrena who played for Weather Report, and Peruvian drummer Alejandro Acuna, another member of Weather Report. Don Alias also played claves, Manolo Bradrena doubled up on coffee cans and Alejandro Acuna added the sound of a cowbell. The ensemble is rounded out by Brazillian jazz drummer Airto Moreira on surdo (bass drum) and Jaco Pastorius playing bongos. Vocals were also recorded and set in the back of the mix. These vocals consist of a call and response in a northern South American or Caribbean dialect of Spanish. Manolo Badrena sings the lead part with Joni Mitchell, Don Alias, Chaka Khan and Alejandro Acuna singing the responses. There is an approximation of the English wording of these lyrics on JoniMitchell.com translated by Wally Kairuz, an Argentinian academic and long time fan of Joni Mitchell. Badrena is exhorting his listeners to ‘dance to my rumba’ and take pleasure in the dance. ‘The Tenth World’ takes the listener out of the artificial, materialistic, decadent, somewhat surreal, circus-like atmosphere of the American resort city of Miami that Joni described in ‘Otis and Marlena’ and into what she referred to as the Third World. The term Third World has its origins in the Cold War and was coined as a reference to nations that were neither aligned with NATO (the First World) nor with what was known as the Communist Bloc which was comprised of the USSR, China and Cuba at that time (the Second World). The Third World encompassed a large number of nations in Africa, Latin America and Asia that had been colonies of mostly European powers. Later the term became more generalized and took on the connotation of economically underdeveloped countries. On ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’, the song ‘Dreamland’ follows ‘The Tenth World’ and closes the third side of the album. ‘Dreamland’ was one of the songs on the demo tapes that Joni recorded before making ‘The Hissing of Summer Lawns’. Joni had actually given the song to Roger McGuinn who recorded it on his 1976 album ‘Cardiff Rose’. ‘Dreamland’ is described as ‘a long, long way from Canada, a long way from snow chains’ where ‘donkey vendors slicing coconut’ have ‘no parkas to their name’. There is a reference to the European imperialism that colonized and exploited much of the Americas in the 15th & 16th centuries ‘Walter Raleigh and Chris Columbus come marching out of the waves and claim the beach and all concessions in the name of the sun tan slaves’. There is also a sense of underlying racially induced tension as Joni pictures ‘Tar Baby and the Great White Wonder talking over a glass of rum burning on the inside with the knowledge of things to come’. But the singer takes the standard from Raleigh and Columbus and describes how ‘I wrap that flag around me like a Dorothy Lamour sarong and I lay down thinking national with Dreamland coming on’. The tourists have obviously come for the party atmosphere, carrying their decadent self-abandonment out of the gateway city of Miami to the Caribbean or perhaps to the South American continent. ‘Good Time Mary and a fortune hunter’ are ‘all dressed up to follow the drum, Mary in a feather hula-hoop, Miss Fortune with a rose on her big game gun’. After all the ‘gambling out on the terrace and midnight rambling on the lawn’ is over it is time to pack up and leave: ‘On a plane flying back to winter in shoes full of tropic sand, a lady in a foreign flag on the arm of her Marlboro Man’. With the knowledge of the weather report of ‘six foot drifts on Myrtle’s lawn’ the travelers ‘push the recline buttons down with Dreamland coming on’.

The final side of ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’ is another triptych of songs beginning with the album’s title track. Don Juan could be a deliberately cliched reference to the Spanish fictional character from the 17th century, famous for his seductive way with women. It is also possible that the Don Juan of the title is a reference to Don Juan Matus, the Native American Yaqui ‘man of knowledge’ whom anthropologist author Carlos Castaneda claimed instructed him in the magical practices of shamanism. Castaneda described this training in a series of books, the first of which he titled ‘The Teachings of Don Juan’. There is a sense of the mystical in the line ‘out on the vast and subtle plains of mystery a split-tongued spirit talks’ and the lyrics contain multiple references to ‘the eagle and the serpent’, animals that appear in Castaneda’s books as symbolic images. Toward the beginning of the song Joni declares ‘I come from open prairie’ and describes the dual nature of her character as ‘given some wisdom and a lot of jive’. The promise of an open, nurturing, relationship described in ‘Jericho’ seems to have been illusory as she sings ‘last night the ghost of my old ideals reran on channel five’. Instead of open communion with her lover, there emerges what seems to be a constant battle between honesty and deception, courage and cowardice, temperance and hedonism, fidelity and indulgence in sexual curiosity. The lyrical content of ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’ is crammed with contrasting images that depict negative and positive aspects of human nature and how they affect American culture and sexual relationships. She uses the eagle and serpent imagery ‘coils around feathers and talons on scales’, to imply that these characteristics are inextricably intertwined in both sexes leading to the conclusion that she and her lover ‘are twins of spirit no matter which route home we take or what we forsake’. Her critical eye is turned on the USA as she indicts ‘here in Good Old God save America the home of the brave and the free we are all hopelessly oppressed cowards of some duality, of restless multiplicity’. Joni describes the national character as restless and constantly vacillating between the reckless decadence of ‘streets and honky tonks’ and the morally sanctioned safety of ‘home and routine’. The pervasive restlessness ‘sweeps like fire and rain over virgin wilderness, it prowls like hookers and thieves through bolt locked tenements’. Joni once again admits her own conflicted sensibility, hidden ‘behind my bolt locked door’ where ‘the eagle and the serpent are at war in me, the serpent fighting for blind desire, the eagle for clarity’. She knows that inevitably she and her lover are ‘going to come up to the eyes of clarity and we’ll go down to the beads of guile’ coming to the dualistic conclusion that ‘there is danger and education in living out such a reckless lifestyle’. Each partner is a composite of both sinner and saint as the song concludes:

Man to woman

Scales

to feathers

You and I

Eagles in the sky

You and I

Snakes

in the grass

You and I

Crawl and fly

You and I

The background vocal sings ‘By the dawn’s early light’ before the final ‘You and I’, once again referencing the US. In an article titled ‘The Education of Joni Mitchell’ by Stewart Brand in Co-Evolution Quarterly from June of 1976, Joni is quoted:

‘The Castaneda books, are a magnificent synthesis of Eastern and Western philosophies. Through them I have been able to understand and apply (in some areas) the concept of believing and not believing simultaneously. My Christian heritage tends to polarize concepts; faith and God - doubt and the Devil - it creates dualities which in turn create guilt which impedes freedom.’

As an interesting side-note to the symbolism Joni attached to the eagle and the serpent in ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’, Nietzche, a philosopher whom Joni has admired since she first read his work, also used the two animals in ‘Thus Spoke Zarathustra’. But in ‘Zarathustra’, Nietzche portrays the eagle as the representation of human pride and the serpent as the symbol of wisdom.

‘Off Night Back Street’ follows ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’ and it is a description of a relationship that has degenerated into sexual infidelity and mistrust. Joni warns that ‘loving without trusting you get frostbite and sunstroke’. Her lover has found a new partner who has moved in with him ‘keeping your house neat and your sheets sweet’. But the sexual and emotional ties are not yet broken and now the former partner has become the man’s ‘off-night back street’. The singer tells him ‘I can feel your fingers feeling my face, there are some lines you put there and some you erased’. The love affair has been both corrosive and healing. As the song ends, suspicion and jealousy seem to have the last word:

You give me such

pleasure

You bring me such pain

Who left her long black hair

In

our bathtub drain?

The final song on ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’ interweaves traditional folk song lyrics with Joni’s words into a fabric of disillusion with romantic love. The words to ‘The Silky Veils of Ardor’ are mostly adapted from the American folk songs ‘The Wayfaring Stranger’ and ‘Come All You Fair and Tender Ladies’. Joni casts herself as the ‘poor wayfaring stranger traveling through this world of woe’ who warns ‘all you fair and tender school girls’ to

Be careful now when

you court young men

They are like the stars

On a summer

morning

They sparkle up the night

And they're gone

again

Daybreak gone again

In the lyrics of the album’s title song, Joni wrote ‘our serpents love the....romance of the crime’. In this final song she laments ‘what a killing crime this love can be’. She longs for ‘the wings of Noah’s pretty little white dove so I could fly this raging river to reach the one I love’. But in this final summing up of the difficulties and imperfections of love relationships, there is no way to fly above the rough waters and she concludes ‘we’re going to have to row a little harder now, it’s just in dreams we fly, in my dreams we fly’.

The positive and negative aspects of romantic relationships, the flawed aspects of human nature, especially in the USA’s cultural atmosphere of 1977, and the dubious, uneasy mixing of indigenous peoples in the Americas with the descendants of their European conquerors all contribute to the broad thematic scope of ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’. Dream states serve as links from one musical progression to the next. As Joni says of Marlena as she sits on her tenth floor balcony in the Miami Royal, ‘it’s all a dream she has awake’. These elements are all concentrated in and perhaps spin out of ‘Paprika Plains’. In this way Joni stitches the various themes of her ‘experimental’ album together.

Musically, ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’ relies heavily on the interplay of Joni’s guitar and Jaco Pastorius’s bass. Jaco was the sole bass player on the album and played bass on all but four tracks. His role as a lead player comes into full bloom on ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’. Henry Lewy said Jaco’s playing was often double-tracked to give the bass an even fuller sound on the record. The bass is prominent in the mix where it is heard, adding lines that are often primary to the musical foundation. Jaco and Joni are the only players on ‘Talk To Me’ providing a musical counterpoint and metaphor for the song’s lyrics as the bass and guitar engage in a musical conversation of their own. John Guerin once again is the drummer on the majority of the album’s tracks. Larry Carlton plays guitar on ‘Otis and Marlena’. Alejandro (Alex) Acuna described how Joni asked him to go on tour in a 2013 interview conducted by Dave Blackburn for JoniMitchell.com. The sound of ankle bells Acuna wore to perform a Peruvian dance was recorded as part of the mix for the song ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’. Joni wanted Alex to perform the dance as a feature of the performances on the tour. Acuna declined the offer, citing his large family and increased demand for session work in Los Angeles as the reasons for his decision. Don Alias who had played with Miles Davis, Weather Report and Carlos Santana played bongos on ‘Jericho’ in addition to his work on ‘The Tenth World’ and played shaker on the album’s title track. Airto Moreira continues to add the sound of the surdo to the Latin American rhythms of ‘Dreamland’ along with Monolo Badrena on congas, Jaco Pastorius on cowbells, Alejandro Acuna playing shakers, Don Alias doubling up on snaredrum and sandpaper blocks with Chaka Khan providing background vocals. Besides the tag for ‘Paprika Plains’, Wayne Shorter also played on ‘Jericho’ and Mike Gibbs added another orchestration to ‘Off Night Back Street’ with Don Henley and J.D Souther singing backup vocals for that particular track. The low pitched voice heard deep in the mix of ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’ as The Split Tongued Spirit is credited on the record’s jacket to El Bwyd. According to McGill music professor Lloyd Whitesell’s book, ‘The Music of Joni Mitchell’, El Bwyd is artist Boyd Elder. Boyd Elder created album cover art for The Eagles and several other artists in the 70s. He also ran a graphic design company called El Bwyd de Valentine M.F.S. Joni accompanies herself solo on guitar for the album’s closer, ‘The Silky Veils of Ardor’.

Joni as Art Nouveau

‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’ was released in December of 1977 to mixed reviews. Some reviewers questioned whether the amount of material merited the release of a double album with the inference that it was a marketing ploy to drive up the price. Some critics lauded the experimental nature of the album while others dismissed it as Joni Mitchell opportunistically using her status to foist her musical experiments off on her fans. In retrospect, the record was underrated by the music press and for the most part its innovative and inventive sounds were either overlooked or minimized. The album peaked at number 25 on the Billboard 200 chart. Although it was certified gold by the RIAA within three months of its release, the chart position seemed to indicate a downward trend in Joni’s record sales.

Georgia O'Keeffe

Although John Guerin played drums on most of the tracks for ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’, his romantic relationship with Joni had definitely concluded its final act sometime before the record’s release. In an interview published in The Washington Post in August of 1979 titled ‘The New Joni Mitchell’, Joni indicated that she had been living with Don Alias for the previous two years. In this interview she also said there was the possibility that the two musicians would get married and there was even speculation about the couple having children. Joni had entered into another relationship with a man with whom she was obviously deeply in love.

Joni’s renewed interest in painting was perhaps responsible for a kind of pilgrimage she made sometime around the time of the release of ‘Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’. Joni and a friend drove to New Mexico to meet the artist Georgia O'Keeffe. O’Keeffe had been painting the desert landscapes of northern New Mexico since 1929 and had been living there permanently since 1949. Joni greatly admired the artist’s work, known for its exquisite use of color in depicting the expansive and endlessly varied landscapes of the southwestern American desert. O’Keeffe also created imaginative visions of large, precisely delineated, close-ups of flowers and animal bones suspended over her sweeping landscapes and expansive blue desert skies. In 1976 a finely executed coffee table book was published of prints of O’Keeffe’s paintings accompanied by her commentary about them. Reproductions of the posters for The Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival that had featured O’Keefe’s artwork since 1972 had also begun to appear in bookstores and gift shops throughout the US. Joni was fascinated with O’Keefe’s paintings when she and her friend drove to New Mexico with the intention of finding Georgia’s home. O’Keeffe was living in an old hacienda she had purchased in 1945 near Abiquiú, a small village about 50-60 miles northwest of Santa Fe. En route to this remote location, Joni and her friend stopped in Santa Fe and sat talking in a place that Joni said ‘promised to be a jazz club’. There were people in the bar who apparently recognized Joni Mitchell and came up to the table to talk to her. Joni began to feel annoyed by the repeated interruptions of her quiet talk with her friend and during an exchange with one fan who said she ‘had to’ approach Joni, a conversation ensued. Joni understood the girl’s need to take advantage of an opportunity to make contact but felt that it would have been more appropriate for the girl to send a note or find another way to communicate her admiration rather than interrupt Joni’s conversation with her friend. The incident set Joni’s thought process about her own desire for privacy in motion and she began to get cold feet about invading the sanctuary of Georgia O’Keeffe’s home since she had never met the reclusive painter. The two drove to Georgia’s property and initially Joni slipped a package under the gate and was ready to leave. But her friend persuaded her to go up to the house. She walked around to the side of the house and saw O’Keeffe in her kitchen. “She looked at me, our eyes engaged from about forty feet, she tossed her head back and stormed out of the room. I knew exactly how she felt." There was an interesting coda to this incident. As Joni tells it, “When I got home there was a copy of Art News with Georgia O'Keefe on the cover. I opened it up and in the article, in enlarged print under a photograph was: 'Georgia, if you come back in another life, what would you come back as,' and without missing a beat it said, 'I would come back as a blonde with a high soprano voice that could sing clear notes without fear.' There it is, I thought, I didn't have to see her, there's something star-crossed about us.” Although this journey to New Mexico was unsuccessful as a foray into O’Keeffe’s private world, Joni eventually met the iconic artist and the two formed a tentative friendship. In a 2014 interview for Maclean's Online Joni recalled her relationship with the great painter:

“She was a testy old bird. She reminded me of my grandmother. When I first visited her, I left her a book of my drawings. She didn't like that and threw her head back like, "Oh for God's sake" and left the room. Months later, I was reading an interview with Georgia and she was saying, "In another life, I would come back as a blond soprano who could sing high, clear notes without fear." I visited her many times afterwards. She confided in me, "I would have liked to have been a musician too but you can't do both." I said, "Oh yes you can," and she leaned in, like a little kid, and said, "Really?" They gave her a hard enough time as it was as a woman painter! She told me that the men said she couldn't paint New York City and she did anyway. “