EMILY APRIL ALLEN

How could you not be thrilled at Joni Mitchell's surprise 2022 appearance at the Newport Folk Festival? Here she was, close to 80 and recovering from a brain aneurysm, performing her first full-length concert in over two decades, with musical and emotional support from her chief booster, Brandi Carlile, and a host of other musicians.

And yet, the set list offered only a narrow glimpse of her eclectic body of work, mostly the confessional pop-folk songs of the 1960s and 1970s: "Help Me," "Both Sides Now," "The Circle Game." The performance did not reflect her grasp of jazz, fusion, rock, weird synths, and song suites. Lovely as it was, the set list oversimplified Mitchell.

Call it the Era Tour.

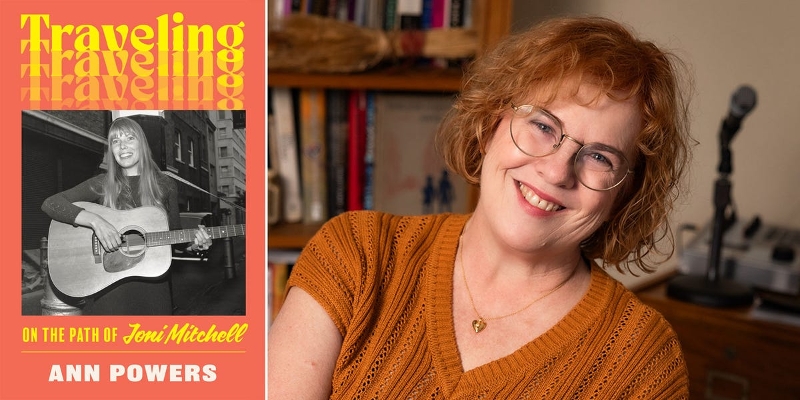

In the lively Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell, veteran music critic Ann Powers's admiration is abundant - indeed, she writes, "inexhaustible." But while recognizing Newport as "the breakthrough moment of her septuagenarian redemption arc," Powers is determined to upend and unsettle the received wisdom about her subject. The result is a book of penetrating criticism, one that takes Mitchell's obscurities as seriously as her highlights and puts her work in broader cultural, musical, and sexual contexts.

Some of these reassessments are relatively minor, such as questioning Mitchell's favored origin story - that a childhood bout with polio shaped her as a songwriter. More likely, Powers argues, being an only child and giving up a daughter for adoption at age 22 were possibly deeper influences; after all, they fueled classics like "Little Green." At the same time, Powers makes substantive points about how Mitchell gathered muses (Leonard Cohen, the inspiration for "A Case of You"), Laurel Canyon guides (David Crosby, who produced her first album), and romantic partners (Cohen and Crosby, along with Graham Nash, who wrote "Our House" with her in mind). Mitchell was threading a needle, asserting her talent while recognizing that, in the early years at any rate, she had to play a man's game. To create herself, she retained access to the folk-rock boys' club while often keeping the boys (and the girls) at arm's length.

Such a predicament may have been unwelcome, but it helped her develop the fluidity that defined her art, allowing Mitchell the ability to manage "what few women could: she moved through her time with the boys and came out her own woman." She did it largely by asserting herself as a songwriter, particularly as she became more entranced with jazz during the 1970s. The period produced some of her knottiest, most inspired work, including The Hissing of Summer Lawns, Hejira, and Don Juan's Reckless Daughter. Powers's greatest insight is that, contrary to conventional wisdom, Mitchell never stopped working as a confessional songwriter. But that searching quality emerged now in the music as much as in the words, as she recruited nimble players - among them, bassists Larry Klein (whom she would marry) and Jaco Pastorius - to help explore her seeking, quicksilver nature.

The move was more in keeping with literature than pop music; Powers neatly bounces "River" off Joan Didion's Play It As It Lays, and contextualizes her work with that of Don DeLillo and Ann Beattie. If Mitchell had reached her creative peak, Powers writes, at a time where "everybody had a shrink and a stack of self-help paperbacks in the den and talked that jargon with the ease and enthusiasm of the newly enlightened...she remade the song form to reveal her inner journeys."

If finding her way meant collaborating with Charles Mingus, or squawking like a chicken (on "Talk to Me"), so be it.

The problem with Mitchell so aggressively shedding personas - girl folkie, singer-songwriter, boho-pop hitmaker - is that she also acquired some problematic ones. Powers writes astutely about Mitchell's little-discussed (and never disowned) foray into blackface, adopting a stereotypical persona named Art Nouveau who is featured on the cover of Don Juan's Reckless Daughter. "She didn't just cross a line - she refused to acknowledge its existence," Powers writes. "It matters, saying this out loud, not wishing away what she's done." Recognizing her own limitations as a white critic, she asks a Black scholar, Miles Grier, to add insights.

Powers's strategy of looking at each iteration of Mitchell's career thematically - sex, race, domesticity, the emotions women are and aren't permitted to express - is a virtue in that it helps keep the book from sagging in its later portions, the way so many rock books do. Little-loved albums like 1985's Dog Eat Dog are opportunities to explore Mitchell's expanding musicianship and embrace of synthesizers; Grammy-winning records such as Turbulent Indigo (1994) illustrate how Mitchell's perception of relationships and marriage evolved. Powers understands that the entry point for many readers is likely Blue or Court and Spark, but her point is that what we love about Mitchell isn't the particular songs or albums but rather the sensibility reflected in the book's title - that Mitchell refused to stay in one place and always went her own way, even if we didn't always feel like following along.

"Her songs themselves formed an argument against her being treated like a sacred cow," Powers writes. "This made me wonder if I could find another Joni Mitchell, one less worshipped but better understood." Powers offers no grand unified theory of Mitchell, but she does make clear why it's worth searching for one.

Copyright protected material on this website is used in accordance with 'Fair Use', for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner(s). Please read Notice and Procedure for Making Claims of Copyright Infringement.

Added to Library on July 25, 2024. (1519)

Comments:

Log in to make a comment