"I would have to say, of all women I've heard, Joni Mitchell had the most profound effect on me from a lyrical point of view." - Madonna, 1997

By the time she got to Woodstock they were 25,000 strong - and it was twenty-nine years too late. But Joni Mitchell cared not that this year's re-staged festival was just a muted echo of the earth shaking original, because there was great personal significance in her performance: The rapturous audience response confirmed the homecoming of an imperious and original figure who somehow became a self-described "expatriate from Pop music."

After almost two decades in the wilderness, Mitchell has seen her reputation restored by a furious flurry of industry awards and critical hosannas. Strangely enough, the comeback might not have been necessary had she managed to carve her name into rock history at the 1969 Woodstock instead of getting stranded in Manhattan. (Mitchell wrote the anthemic 'Woodstock' in David Geffin's apartment.) Then again, she probably wouldn't have fitted in there, either.

"A lot of hippie politics were nonsense to me," says Mitchell, now fifty-four. " I guess I found the idea of going from authority to no authority too extreme. And I was supposed to be the 'hippie queen,' so I had a sense of isolation about the whole thing.

"I've always had different perspective - an artist is a sideliner, not a joiner; they must have certain clarity and depth, which is burdensome and really inconvenient for fun." Mitchell pauses. Then she laughs uproariously.

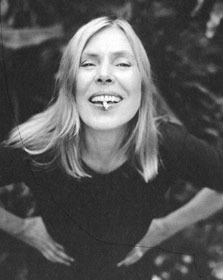

Yes, despite her ice princess image, Joni Mitchell likes to laugh - loud and often. In fact, according to Mitchell, old hometown friends knew her only as a high stepping dancing queen and "good-time Charlie" until they heard her sing.

Those friends were blithely unaware of a key component in Mitchell's make-up, as was everyone until recently. At age twenty-one, she gave up a baby daughter for adoption. "I had bottomed out," says Mitchell of her subsequent work. "I had lost my child, and I was grieving a tremendous loss. At the same time, I found myself swept up in this tremendous popularity. That had a lot to do with my introspection and my deepening.

Mitchell's lyrical allusions to an estranged child were eventually investigated by the press and ultimately splashed across tabloid headlines. Last year, thirty-two year old Canadian Kilauren Gibb guessed correctly that she was the child in question and contacted the singer. Kilauren (nee Kelly), a former model, and her son are currently visiting Mitchell's Los Angeles house.

Outside the Hotel Bel Air, the summer lawns hiss. Inside, a fake log fire flickers light on a photo gallery of European royals and American conservatives. Nancy Reagan, as it happens, is lunching today in the hotel's dining room. In a distant suite, Joni is in the process of launching her new album, Taming the Tiger.

This hill-bound enclave of Hollywood's ancien regime is Mitchell's neighbourhood. She lavishly praises the European craftsmanship of many Bel Air dwellings and recalls the days when she'd see the likes of John Wayne and director John Ford at parties. "The world seems to have no class anymore," she says.

Class and craftsmanship may these days be little-valued commodities, but to Mitchell they are articles of faith - and she can be most cruel to non-believers. Her diatribes against shabby and derivative music are as entertaining as the are piercingly accurate: Just one jagged little quip left fellow Canadian Alanis Morissette in tears.

Expect neither politic quote nor prudent career move from the newly respectable Joni Mitchell. "Playing the game is repulsive to me," she insists. "You're still gonna get dumped after a couple of years - then you're compromising yourself and you're dumped. The dumping is inevitable, so I'd rather not compromise. I'm in it for the musical adventure."

Both Mitchell's ostracism and her ultimate survival can be ascribed to the inviolable ethos, forged long ago and far away. She as born Roberta Joan Anderson in 1943 in Alberta, Canada, and was raised in the shadow of the Great Depression. At nine, Mitchell, a rangy, athletic child, contracted polio and was warned that she might never walk again. During a determined and successful convalescence, Mitchell developed an inner life that made her down play her own intelligence. "I didn't want people to think I was an egghead, so I became an anti-intellectual," she says.

Mitchell plucks a fresh pack of American Spirits from the carton by her side. She started smoking at age nine, when she was the only choirgirl who could be trusted with the complex descant parts. She was forever out of step with her times, accruing the kind of experience that sharpens a writer's eye for contemporary mores. In the blackboard jungle Fifties, she was feared and reviled by her elders as the "first teenager on her block; and as an aspiring folk singer in the early Sixties, she flouted the morality at the time by bearing a child out of wedlock.

After penning several hits for other performers, Mitchell made her solo debut in 1968. The world was hardly screaming for another flaxen haired folkie, but Mitchell cut through the clutter with her crystalline voice and what she calls her "classical-meets-Forties-standard-synthesis." Not to mention those words, which made other rock lyrics sound like bumper sticker slogans.

The sensual and cerebral newcomer recorded a string of brilliant, finely wrought albums while rejecting the endorsed producers and musicians of the day. "It wasn't about commercial success for me - I didn't want to go dumb," says Mitchell, who felt patronised when she'd try to explain her vision to potential collaborators. "Music is like sex," she notes wryly. "It's difficult to give instruction to a man."

Mitchell found satisfaction in the lissom form of LA Express, the jazz outfit that provided the backdrop for her sixth album, Court and Spark. Her poetic pathology of high life in the "city of fallen angels" is today seen as the gold standard for literate songwriting, but at the time her rarefied vignettes offended guardians of "authenticity" in rock: Pondering one's post-hippie affluence in public was just not done.

"They called them 'rich people's problems," says Mitchell. "But I have to scrape my soul to write songs, and I had a lot of spiritual/material conflict at the time. I was trying to reconcile a climate that had genuine leaning toward the spiritual and stylish leaning toward the spiritual. That kind of thing is okay if you're a playwright, but not if you're a singer."

On The Hissing of Summer Lawns, Mitchell's lush soulful meditations on spiritual / material conflict were wrapped in a picture of the bikini clad artist in her pool, floating in an apparent state of ennui deluxe - hardly likely to endear Mitchell to critics who accused her of being pretentious when the weren't bemoaning her lack of hummable tunes. Her exile from the mainstream was completed in 1979, when her beatnik spirit moved her to record Mingus, an esoteric collaboration with the ailing jazz giant Charles Mingus.

The Eighties brought Mitchell problems with business managers, banks and taxes; she was "butchered" by a negligent dentist and produced by Thomas Dolby. And despite the fact that she created much of value in the MTV decade, Mitchell was effectively invisible. "I felt like Garbo when they didn't want her to be in the talkies," she says.

The embattled artist found solace in painting and even sold $120,000 worth of her artwork to finance three music videos. The clips were ignored, victims of what Mitchell sees as cowardly form of aesthetic correctness: "There's this tendency to court the new - people are just so afraid not to be hip. I used to start fads as a kid, wearing my father's tie to school, things like that, and I even had a column called 'Fads and Fashions' in the high school paper. I was hip to the hip at sixteen!"

In the circle game that is Joni Mitchell's career, it is somewhat apt that her latest album appears on Reprise, her first label. Taming the Tiger finds Mitchell in fine fettle, albeit shrouding herself swaths of effects-laden digital guitar. She is enthusiastic about her new instrument, which allows instant access to the kinds of tunings that would warp regular axes; plus, she gushes, it allows her to blow up her sound "like Georgia O'Keeffe's flowers."

Mitchell's guitar sound swells to Godzilla-like proportions on the albums sole blemish, an ill-advised rocker called "Lead Balloon."

One of Tiger's many high points is "Stay in Touch," Mitchell's ode to boyfriend Donald Freed. "When we first met, we threw the I Ching," she says. "The book said 'to remember the beginning,' so I kept the essence of the idea and restructured the words. It seemed like a blueprint for proper conduct through the beginning phases of any intense attraction." The track's title proved prescient: The couple recently parted ways.

Although it fits no existing format, Taming the Tiger should advance the rehabilitation of the woman who, on the cover of her last album, Turbulent Indigo, painted herself as a desolate Van Gogh figure. "Well, I was either going to cut my ear off or do it in effigy," she quips. The record was, Mitchell admits, intended to be her swan song. "I was black-listed. What's the point of remaining in the business if you are not allowed to participate?

As she was ostracised for so long, it's not surprising that Mitchell is less than grateful for the Grammys and the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction that have lately been laid at her feet. Her star-crossed journey from first teenage on the block to the last beatnik in rock has surely earned her the right to remain forever a "sideliner." What's breathtaking is the severity of Mitchell's contempt for the club that kept her on the waiting list for so long.

"All of a sudden I'm getting these awards, but nobody really understands why - only that it should be done," says the canonised Canuck, her avid vowel sounds recalling the plains of Alberta. "It was lip service: The speeches didn't illuminate what was, I thought, important about my work - they were kind of half-assed. I wish I was more simple minded so that I could just say, "Thank you for this symbol of achievement in my industry," but I know too much about the manipulation that goes on behind the scenes.

"I also know what honour is - and I have been honoured," says Mitchell firing up yet another American Spirit. "For instance, a black, blind piano player in a restaurant once said to me, 'Joni, you make raceless, genderless music.' That, to me, was an honour."

Mitchell once predicted that she'd end up an "ornery old lady," but even in mid-tirade her bearing is serene, her blue eyes undimmed by the depredations of decades in the cold. Bitterness does not appear to have consumed her yet.

"Well, I am a little bitter," Mitchell confesses with a rueful chuckle. "I'm too underrated for the calibre of work I produce. I've been treated like I'm dead for twenty years by the industry, and people would be called 'the new Joni Mitchell' when they weren't as good as me - then they would turn against me! So I'm trying to heal…. But I've still got some stuff to spit out."

Copyright protected material on this website is used in accordance with 'Fair Use', for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner(s). Please read Notice and Procedure for Making Claims of Copyright Infringement.

Added to Library on December 18, 2001. (6495)

Comments:

Log in to make a comment