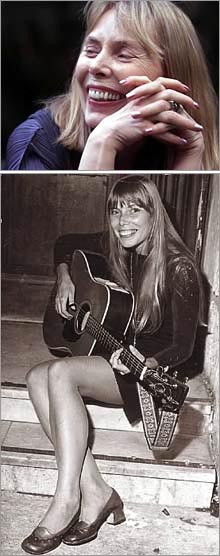

No regrets ... Joni Mitchell reached the willowy female undergrads in the mid-'70s.

The volume and quality of Joni Mitchell's output are matched only by the paucity of critical assessment of her musical work. Andrew Ford examines why she has been ignored.

A lot of people were surprised by Joni Mitchell's latest album, Both Sides, Now. They shouldn't have been. True, the fact that it contained so many songs by other people was new; that these songs were standards was new, too; and the rich orchestrations that cushioned Mitchell's languorous vocals were certainly new. Most of all, I suppose, the voice itself was barely recognisable. Smoky and lugubrious where once it had whooped and swooped, this was a very long way from Chelsea Morning.

But the album reinstated Mitchell as the jazz singer she had been at the end of the 1970s. And among the tunes by Richard Rodgers, Harold Arlen and Vincent Youmans were two of Mitchell's own songs, which, you suddenly realised, it was also possible to think of as "standards". And then, as you took all this in, you realised something else: Joni Mitchell should be vastly more critically regarded than she is.

I think it goes back to the college girl thing. Until the mid-1970s, at any rate, Joni Mitchell's music, like Sylvia Plath's poetry, was almost exclusively the passion of willowy, female undergraduates. They probably had posters of pre-Raphaelite paintings on their walls and copies of By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept on their bookshelves. If they listened to pop music by male artists, these would most likely have been Simon and Garfunkel or Cat Stevens.

The men on that list - Paul, Art, Cat and the pre-Raphaelites - shared a certain gentleness of approach to their arts that the average 1970s male would have found unpalatable (he was still playing his Creedence Clearwater Revival records and getting into Springsteen). But the female artists - Mitchell, Plath and Elizabeth Smart, the author of Grand Central Station - explored human feelings with searing honesty, exposing their emotional nerve endings in a manner that would first have embarrassed, then terrified most men. And who was it that, for the most part, went on to become the music critics?

In Rolling Stone and New Musical Express, the musical credentials of Mitchell's latest lover were more likely to be discussed than the qualities of her latest album. Now it's true the lovers amount to a who's who of rock and jazz, but not as impressive as the list of songs this woman has composed over 35 years.

The recent publication of a collection of interviews, articles and reviews seems only to underline the lack of seriousness with which Mitchell's work is still taken. One of the first things you spot about the book is that it can't quite decide on its title. On the front and spine, it's called The Joni Mitchell Companion, but turn the book over and it seems to be called Both Sides, Now. Back to the front cover and the next thing you see is the misspelling of the author's name.

These errors don't bode well, you have to admit. As it turns out, the contents of the book, though prone to repetition, are an improvement on its cover, but the general paucity of critical writing about Mitchell (compared with, say, the small library of books on Dylan) remains something of a scandal.

Here is an artist with 21 albums to her name, if you count her two compilations of 1996, wryly entitled Hits and Misses. She composed a handful of the late 20th century's most recognisable melodies and she possesses (or at least, she possessed) one of the most striking voices in pop history.

Those are facts. But I'd suggest that more significant still is the quality of her output. Her songs, in my opinion, easily rank alongside Van Morrison's, Neil Young's and Bruce Springsteen's. Even - and perhaps especially - they belong in the same company as Bob Dylan's. And, like Dylan, Mitchell has often undercut her own material, refusing to make it too obviously attractive.

Take Both Sides, Now. Written in 1967, it's without doubt her best-known song and it's one of the standards on the recent album with which it shares its title. In fact it's been a standard for more than 30 years, recorded by such unlikely figures as Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, Andy Williams and Neil Diamond. It was never a hit for Mitchell herself (Judy Collins had the hit with it), but Mitchell's own acoustic version of the song, on the 1969 album, Clouds, is illuminating.

While Collins recorded the famous tune with simple chord changes that moved in step with the melodic line, Mitchell's recording features a drone-like thrumming of the guitar, employing one of her famous, vibrant open tunings, that against parts of the melody is downright dissonant. Where Collins had offered something sweet, Mitchell's version, as befits a song called Both Sides, Now, is bitter-sweet.

Mitchell's music and lyrics are almost always distinguished, quirky and unpredictable, but the space between them is filled with contradiction and tension. On Blue, released in 1971 and still perhaps the best thing she's done, the final song is very unusual in this respect. The melodic line of The Last Time I Saw Richard is unconventional to the point where one begins to doubt there's a tune there at all. You can easily whistle or hum Both Sides, Now. But try humming Richard and you'll quickly discover it makes very little sense without its words.

To all intents and purposes, this song is a form of recitative (minus the operatic delivery), having the tone, rhythm and tempo of real speech. In particular, there is no regular metre; lines don't scan. The line endings of Mitchell's lyrics, as printed on the album sleeve, might be arbitrary:

The Last Time I Saw Richard was Detroit in '68,

and he told me all romantics meet the same fate someday

cynical and drunk and boring someone in some dark cafe.

Mitchell accentuates the conversational manner of delivery by pausing before "'68", as though momentarily searching her memory for the date, and then rushing the next phrase, like someone who's afraid her listener may be tempted to interrupt. Indeed, you begin to wonder whether the singer herself may be "boring someone in some dark cafe". We've all met people like this; people who tell us personal things we might not wish to hear; people who tell us personal things about other people, people we don't even know.

Richard got married to a figure skater,

and he bought her a dishwasher and a coffee percolator

and he drinks at home now most nights with the TV on

and all the house lights left up bright.

But this is only one aspect of the song, the part where the words control the flow of the music. The opposite also happens. The melody keeps attempting to take control; the music wants to take flight in arabesques instead of being tied to the relentless procession of syllables. Finally, as Mitchell sings of getting her "gorgeous wings" and flying away, the song finds its climax, an intense, slow trill on the first syllable of "gorgeous". The singer, finally (though momentarily), breaks free of the song.

This is sophisticated stuff, and the flexibility of phrasing in the performance offers, with the benefit of hindsight, a big clue as to Mitchell's future direction. Three years later, on Court and Spark, she recorded Twisted, Annie Ross's famous verbalisation of Wardell Grey's saxophone solo, and she did it as though born to the jazz purple.

Now she began to work regularly with jazz musicians such as John Guerin, Jaco Pastorius, Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Don Alias and the Brecker Brothers. The climax of this period was her collaboration with the dying jazz great, Charles Mingus. Taking a handful of Mingus's instrumental compositions, Mitchell put her own words to them. For the most part, they're rather wistful numbers (melodically and lyrically).

It was not, perhaps, the wisest change of direction ever taken by a pop singer, since it disaffected precisely the two groups of people whose support was needed if the move into jazz were to succeed. On the one hand, and notwithstanding Mingus's seeming approval of Mitchell, the jazz aficionados sneered, as jazz aficionados will.

And of course on the other hand, the college girls were terribly disappointed. They had spent the early 1970s memorising Mitchell's songs, learning to play them on their retuned guitars and growing their hair. For their pains they were being offered Wayne Shorter saxophone solos.

To my ears, Joni Mitchell had one of the most natural jazz voices of modern times and she seemed to have found her metier in this new material, but as early as 1982, on Wild Things Run Fast, she retreated into a kind of mainstream pop. If she has spent the past two decades keeping pretty much to the middle of the road, however, it must be said that her steering has been growing ever more wayward. Shorter and Hancock have remained frequent guest artists; that fine jazz drummer, Peter Erskine, has kept showing up behind the kit; and finally, last year, came the album of standards.

In a New York Times interview from 1991, reprinted in The Joni Mitchell Companion, the singer tells Stephen Holden that her greatest influence as a singer was Edith Piaf. In 1991, this must have seemed like a bizarre confession, and it is surprising to find it passing without comment in the article. But now that her actual voice has grown that much closer to Piaf's (in range, if not in timbre), the connection is rather more apparent.

Certainly, as she sings Both Sides, Now on the eponymous standards album, the voice dark-toned, bathed in the alternating shadows and light of Vince Mendoza's elaborate orchestral arrangement, there's more than a whiff of defiant resignation about Mitchell. The song, you realise, has become - and perhaps it always was - her "Je ne regrette rien".

Copyright protected material on this website is used in accordance with 'Fair Use', for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner(s). Please read Notice and Procedure for Making Claims of Copyright Infringement.

Added to Library on September 30, 2001. (3253)

Comments:

Log in to make a comment