Ms. Robbins took particular pride in the women’s anthologies she edited and co-edited, and in their explicitly feminist content. Credit...Fantagraphics

Trina Robbins, who as an artist, writer and editor of comics was a pioneering woman in a male-dominated field, and who as a historian specialized in books about female cartoonists, died on Wednesday in San Francisco. She was 85.

Her death, in a hospital, was confirmed by her longtime partner, the superhero comics inker Steve Leialoha, who said she had recently suffered a stroke.

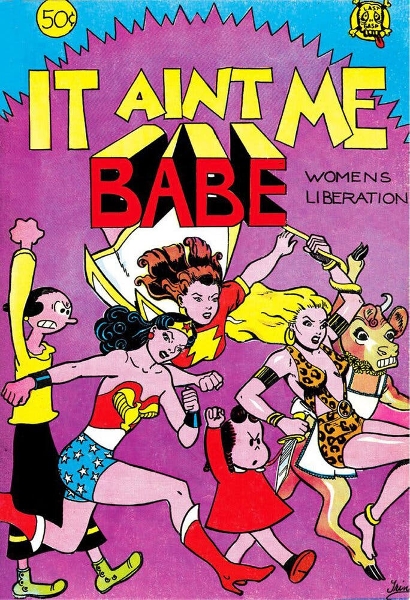

In 1970, Ms. Robbins was one of the creators of It Ain't Me Babe, the first comic book made exclusively by women. In 1985, she was the first woman to draw a full issue of Wonder Woman, and a full run on a Wonder Woman series, after four decades of male hegemony. And in 1994, she was a founder of Friends of Lulu, an advocacy group for female comic-book creators and readers.

The cover of a book with the name "IT AINT ME BABE" (no apostrophe) in large, stylized capital letters and "WOMEN'S LIBERATION" in smaller capital letters, above a drawing of Olive Oyl, Wonder Woman, Mary Marvel, Little Lulu, Sheena Queen of the Jungle and Elsie the Cow, all running, with fists raised and angry expressions on their faces. Ms. Rob

bins took particular pride in the women's anthologies she edited and co-edited, and in their explicitly feminist content.

Before she devoted her life to comics and to the women who make them, Ms. Robbins was an accomplished clothes designer and seamstress in the 1960s, outfitting music stars like Donovan and David Crosby. She became a notable figure in the hippie communities of New York City and San Francisco, and in Los Angeles she caught the eye of Joni Mitchell.

The first verse of Ms. Mitchell's song "Ladies of the Canyon," featured on her 1970 album of the same name, is a portrait of Ms. Robbins:

Trina wears her wampum beads

She fills her drawing book with line

Sewing lace on widow's weeds

And filigree on leaf and vine.

Trina Perlson was born on Aug. 17, 1938, in Brooklyn, the younger of two daughters of Jewish immigrants from what was then Russia but is now Belarus. Her father, Max Bear Perlson, worked as a tailor until Parkinson's disease forced him to retire; her mother, Elizabeth (Rosenman) Perlson, was a second-grade teacher.

At a young age, Trina became obsessed with comic strips and comic books, gravitating to female characters like Brenda Starr, Patsy Walker and Millie the Model. A particular favorite was the fashion plate Katy Keene, who inspired Trina to make dresses for her own paper dolls.

A book cover with the word "Last Girl Standing Trina Robbins" written in what looks like handwriting, and a photo in which a young Ms. Robbins, with long brown hair in bangs, stands against a wall with her arms outstretched. She is surrounded by other young people, all seated, wearing colorfully patterned outfits similar to the one she herself is wearing. The cover of Ms. Robbins's memoir, "Last Girl Standing" (2017), featured a 1966 photograph of Ms. Robbins (center) taken in the singer Donovan's dressing room in a Los Angeles nightclub. Almost everyone in the photo is seen wearing clothes Ms. Robbins designed.Credit...Amazon

She also drew comics: In her 2017 memoir, "Last Girl Standing," Ms. Robbins wrote, "My wonderful mother brought home from school an endless supply of 8½" by 11" Board of Education paper and No. 2 pencils, from which I would chew off the erasers."

When she began high school, her mother told her that it was time to abandon comics, and Trina complied, shifting her obsession to science fiction. In her senior year, she wrote and costumed a sci-fi play called "Twenty Years Later."

After one year at Queens College, she moved to Los Angeles, where she posed nude for pinup magazines in the erroneous belief that doing so would lead to a movie career. In 1962, she married Paul Jay Robbins, a magazine editor; they divorced in 1966. During that time she "locked herself in a room with an electric sewing machine," she was quoted as saying in "Dirty Pictures," Brian Doherty's 2022 book about underground comics; she was soon making dresses, which she sold at craft and Renaissance fairs.

Ms. Robbins befriended members of the Byrds and the Doors and moved between the coasts. In New York City, she opened a clothing boutique on East Fourth Street in Manhattan called Broccoli, a name inspired by a claim she had made, while high, that she could communicate with vegetables.

When she read the alternative newspaper The East Village Other, she was captivated by its surreal comic strips and realized that the doodles she had been making could be comics, too. As a lark, she illustrated, in Aubrey Beardsley style, a one-panel cartoon about a teenage hippie named Suzi Slumgoddess and slipped it under the door of the paper's office. To her surprise, it was printed, launching her career as an underground cartoonist.

Ms. Robbins became a regular contributor to The East Village Other, making comic strips that doubled as advertisements for Broccoli. She often rendered her characters like the dolls that had captivated her as a child, and her strips mined the contrast between that innocent style and taboo-breaking subject matter. When the paper published a comics tabloid called Gothic Blimp Works in 1969, she contributed a strip about having sex with a lion.

Her comics about sex were often playful - the two-page strip "One Man's Fantasy," for example, was about a man captured by a group of attractive women, who force him to make a tuna fish sandwich. But she found that many male cartoonists were threatened by any hint of feminism.

Ms. Robbins was repulsed by the dark material in Robert Crumb's comics and the way the underground scene followed his lead. "Rape and humiliation - and later, torturing and murdering women - didn't seem funny to me," she wrote in her memoir. "The guys told me I had no sense of humor."

Ms. Robbins was responsible for the first publication of some notable cartoonists in The East Village Other, including Vaughn Bode and Justin Green, but she took particular pride in the women's anthologies she edited and co-edited, and in their explicitly feminist content: It Ain't Me Babe Comix, Wimmen's Comix and the erotic Wet Satin.

She also designed the famously skimpy outfit for Vampirella, a female vampire who appeared in black-and-white comics beginning in 1969 - although her design was not as skimpy as the costume later became. "The costume I originally designed for Vampi was sexy, but not bordering on obscene," Ms. Robbins told the Fanbase Press website in 2015. "I will not sign a contemporary Vampirella comic. I explain, that is not the costume I designed."

Along with Mr. Leialoha, her partner since 1977, she is survived by Casey Robbins, her daughter with her fellow cartoonist Kim Deitch; a granddaughter; and her sister, Harriet Nadel.

Copyright protected material on this website is used in accordance with 'Fair Use', for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner(s). Please read Notice and Procedure for Making Claims of Copyright Infringement.

Added to Library on April 12, 2024. (2924)

Comments:

Log in to make a comment