It's all too easy to flatten a figure like Joni Mitchell, to take for granted her peerless body of work, her constant drive, the way her words can ache and cut, sway and celebrate. On the other side of the 20th century, she seems to have always been around - a beacon to whole generations of inventive musicians and performers: from Mitski, St. Vincent, and Lana Del Rey, a mother to artists as various as Prince (who'd pen fan letters as a teenager) and Kate Bush, a peer and muse to a guilded cohort of rock stars and folk legends like Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young, as well as Bob Dylan. Famously considering herself a painter first and foremost, she is far more than "just" a singer-songwriter with a singular voice (though hers, with its fluctuations and range, is doubtless one), far more than a criminally underrated guitarist, arranger, and wordsmith (though dude guitar gods like Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page certainly learned a thing or two from her) - she seems, at least within the lens of collective memory, to arise as a kind of force, a totality.

But, of course, since we're talking about an era in popular music and culture whose gates were kept and levers were operated by white men (as they still mostly are) - a machine whose gears were and are fueling and fueled by patriarchal assumptions and judgements - she got a lot of flack, not only for her sexual freedom, unconventional approach to relationships, and the way she wrote about men, but her free and unconventional approach to her own career. Rolling Stone published a diagram depicting her famous lovers (reinforcing in her a lifelong distrust of publicity and fame), dubbing her, cruelly, "Queen of El-Lay" and even "Old Lady of The Year." (This actually prompted her to black out talking to the publication for seven years.) In a manner that she herself was all too aware, Joni Mitchell was spun up to be at once a very serious, buttoned-up, intellectual, and earnest artist who didn't play by the traditional rules of femininity, while also playing the role of seductress. It's of course a legend that falls apart under closer scrutiny, but has always had wings. Though she is indefinable, an artist always stepping forward, a shapeshifter, she nonetheless was always being defined within the patriarchal box, seen and heard through the eyes and ears of men.

Time and memory can make a caricature of anybody, and this can especially be true in the case of a singer-songwriter whose life, fairly and unfairly, is always read into her work. And regardless of how much Joni may have put stock in such things - she's always been cynical about media representation and the trappings of fame - there was something about her that made her a tantalizing figure and a star. Male journalists loved to love her until they learned to hate her and back again. Throughout her career they have cast as her as the folk queen who crossed over - the queen of LA's Laurel Canyon set beaming as she charmed her audiences. Of course, and inevitably, she becomes the femme fatale of the shaggy set, the pretentious artist, the rich hippie past her prime, and eventually the one who ditched it all for jazz. But in spite of being described in the language of the patriarchy, she's come to be appreciated for the fearless trailblazer she always was: for the woman who built herself a home to work in and who chronicled the road she always felt she must travel, and the rest of the world traveled with her.

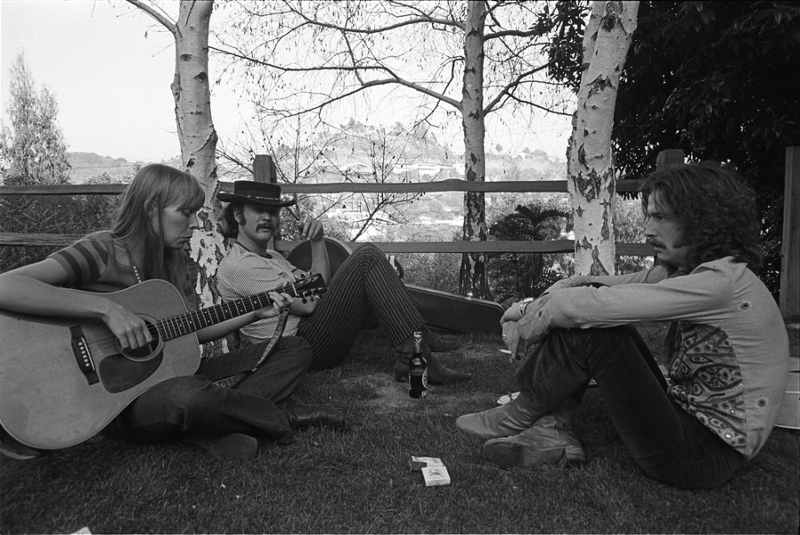

Mitchell's stature among her fellow male musicians was certainly a source of wonder, perhaps even jealousy. Singer-songwriter and writer Leonard Cohen - fellow Canadian, early lover, and musical peer who rose to prominence around the time she did - characterized her as "a musical monster" whose songs arose fully-formed "like a storm." Another ex-lover and the one that ended up bringing her into the pop mainstream, David Crosby (The Byrds; Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young), was similarly smitten - at once intimidated by her boundless talent and hopelessly attracted to her; "she just knocked me on my ass," he's said. But what they and many other men, musical and otherwise, latched onto - and how she's been largely depicted by the musical press - is also, inevitably, draped in artifice, in mirages they, themselves, were concocting. You don't fall in love with a person so much as your idea of them; that seems to be one lesson you find in Mitchell's music. And much as she resisted it - few pop stars seem as invested in being true to themselves creatively - a certain aura surrounds and has always surrounded her.

And the aura looms largest is the one coming from the Joni of Laurel Canyon, of 1969; the Joni that settled into the Lookout Mountain house (a sanctuary that was close to Sunset Blvd., but didn't feel like it) and quickly became an integral part of a whole scene. There it was that she and Graham Nash fell in love, and where, in turn, he would join forces with Crosby and Stephen Stills. For a time - one we access mostly from songs, in memoirs, in photographs - they built their utopia which became a hub of a community of artists loving each other and goading each other on. It was a fiercely productive time for both artists, and Nash, finding a moment when their shared piano was free, penned "Our House," an ode to their domesticity. Theirs is "a very fine house/ with two cats in the yard" (such a neat image for the couple), which would appear on Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young's 1970 album, Deja Vu, and become a wedding song staple. In Nash's gaze, Joni is a balance of domesticity and artistic activity, who decorates but also plays "love songs all night for me, only for me" Their love didn't last - Joni's songs are not the provenance of one man - but it was a beautiful dream: no paradise, no matter how idyllic, lasts forever.

However, if you are listening to "Our House" on their compilation record So Far and you go back one track (if you hit "Ohio" you've gone too far), you land on the boy's version of one of Mitchell's most iconic songs: "Woodstock." And with that masculine makeover came a superficial nostalgia that veers slightly from Joni's actual intent. With the imagery that was equal parts graspable and glorifying, she captured the last gasps of idealism and escapism of the Woodstock festival; a spectacular event that, looked back upon now, seems to have been the crest of the '60's counterculture wave. In other words, she was brutally summing up the failure of the counterculture movement itself, the festival goers trying to hold on to something already lost. However, in Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young's rendering, the song depicts a paradise that has returned (even if only for a moment) from the perspective of having been there and a little reworking of the lyrics - they made it sound like a rock n roll retelling. Boisterous, and urgent, the harmonies soar above, carrying the collective feeling that love can overwhelm the whistles and whoops of war, emphasizing the idea of being made of carbon, as opposed to Joni, the author, putting the emphasis on our being caught in the devil's bargain. They released it on their 1970 album Deja Vu, the same time as Joni's own version appeared on her classic 1970 album Ladies of the Canyon, and when the hippy movement all of the sudden felt like it was turning into a distant memory.

Joni's original telling of "Woodstock" seemed to capture more of a sense of wistfulness, superficiality, and longing. "We are stardust/we are golden..." accompanied only by organ and some back-up singers, and voiced in the way that only Joni could, it's a masterpiece of melancholia. Seeing from the outside, (as she famously stayed behind and watched the whole show on TV) Joni was able to capture a fuller picture; she seems - with the power of her voice, and thanks to a brilliant, minimal arrangement - to somehow have drawn the curtains on the 1960's once and for all. Listening to the original version of "Woodstock," you can't help but feel that it was over before it began, that, contrary to what the 400,000 or so that came to Woodstock hoped, it was in fact, the end. Her song, then, as she wrote it, was an elegy.

And so, from the wreckage of the '60's, while wearing its armor, Joni's reputation as beautiful, profoundly musical, but completely uncompromising artist - as a kind of standard bearer for a whole generation - began to build. As depicted in Hammer Of The Gods, journalist Stephen Davis's definitive (but unauthorized) biography of Led Zeppelin, lead-singer Robert Plant, then at the height of his powers (ahem and also debauchery and womanizing), was famously too shy to even speak to Joni when the chance arose in the early 70s. She - the consummate artist, the peerless writer and singer - was actually intimidating to the front man of the superstar band in an era, in fact the era, of the male rock god. "Going To California" - Led Zeppelin's love-letter to Joni - references her early song, "If I Had a King," and is a lyrical and stylistic response to "California," from her 1971 album Blue. Joni, as gazed at by the narrator sung by Plant, is the "girl with love in her eyes and flowers in her hair" and later "a queen without a king" who "plays guitar and cries and sings." And surely Jimmy Page's bright, picked acoustic guitar is an homage to the subtle, melodic textures that were Mitchell's stock-in-trade at the time.

In both her own conception and especially in the conception of Led Zeppelin - who, as English rockers were likely more invested in the mythology of American authenticity than their American counterparts - California becomes a kind of Eden, a place that makes sense for those who think the rest of the world doesn't - the "girl" is a mystery. But where the Brits spin a tale of longing and wonder - of estrangement, in many ways - it's clear that for Mitchell, California is "home." The central tension in her song "California" - I suppose you could carry the biblical interpretation further, here - is whether she actually has the capacity to return to paradise, whether that return will even square with her memories. Will her vision of utopia actually "take me as I am/ strung out on another man?" Can you go home again? The answer is complicated - the hesitation in the words outlining the dramatic tension in the song - and one senses that it's just as possible that the paradise sought here might indeed be lost in time, that a desire for the road, for love, has squashed the singer's innocence.

As is often the case in popular culture, and certainly in popular music, the first impression tends to be the most lasting and casts the longest shadow. The machinations of how it all worked were no mystery to her. When asked about fame and "fickle" audiences in a 1979 interview with Cameron Crowe for Rolling Stone (her first with the magazine after her personal boycott), Mitchell quipped: "the most you can really get out of it is a four-year run, just the same as in the political arena... You have, possibly, one favorable year of office, and then they start to tear you down." Sooner or later, the public - a consumer culture driven by novelty - will dispose of you, eager for the next big thing. And Joni emerged not just as the bright, young hippie folkie she thought she was, but the plaintive, more introspective and intimate side of the bohemia she came to represent. This - the melancholy, the perfectly balanced universalism as she sings "When the curtain closes/ And the rainbow runs away/ I will bring you incense /Owls by night /By candlelight/ By jewel-light/ If only you will stay" in "Chelsea Morning" (from the album, Clouds) - was the luminous voice that let everyone get to know her, and that, seemingly, they all wanted.

But - see Dylan being decried a Judas when he went electric in 1965, see the fate of most any artist rebelling against the formula that made them first successful - reception to Joni's work cooled when she stepped away from the trappings of being a confessional folk popstar. It cooled when she was seen as undertaking more universal themes (even though she certainly had before), when she turned more towards jazz-rock and jazz, when she followed her artistic instincts and moved on from what defined her earlier work. Experimentation, for an artist with such a distinct aura, is risky territory. Joni, however, was never interested in replication or sticking to any formula other than what spoke to her at any given moment.

As her career rumbled on into the mid and late 70s, she was often trapped critically: the folk pop songstress who was perhaps, a little too sentimental and vibrant in her (now outmoded, unhip) early work had started to dabble, perhaps unseriously, with other idioms. Reviewing her 1979 album, Mingus, a collaboration in which she set words to melodies by the jazz-great, Charlie Mingus (released after his death), Sounds reviewer Sandy Robertson calls out her move towards a "jazzier style," writing "[t]he trouble...is that Joni still sounds as if she should be singing folk songs in coffee houses: technically perfect, but lacking in abandon. Too nice to be nasty." Suffice it to say that her male peers, like Paul Simon, who similarly began moving beyond the singer-songwriter idiom to much acclaim, would never have been criticized in this way. In writing about a 2012 concert he did with Wynton Marsalis and a jazz orchestra, reviewer, Andy Greene enthused that the songs "were enhanced and messaged by the jazz musicians."

There's no doubt that the work she was producing on albums like Court and Spark, Miles of Aisles, The Hissing of Summer Lawns, Hejira, and others - a period truly worth revisiting - were a sure step away from the earlier albums that made her name. The 70s saw her start to work with a who's who of notable jazz and jazz fusion musicians: fusion group, LA Express; inimitable bassist, Jaco Pastorius; jazz guitar virtuoso, Pat Metheny, and so many others. While reception of these albums has rightfully changed over time - most of these albums have become favorites in her body of work - Joni was not treated charitably for stepping out, experimenting, and continuing to develop as an artist. "If The Hissing of Summer Lawns offers substantial literature" wrote critic, Stephen Holden, in a 1976 review of the album for Rolling Stone, "it is set to insubstantial music." Furthermore, the jazz press refused to take her seriously - something perhaps that may have cut harder - basically calling her a hobbyist.

There's a familiar streak of betrayal in the way the press treated her; Joni Mitchell had committed a crime against her perceived authenticity. Where her male counterparts around her were (usually) seen as adventurous and brave when they progressed musically and brought in other influences, there seemed, in the critical imagination, to be less room for female artists to grow, change, experiment, to step out of line. So it's OK for Bob Dylan to go gospel as he did during his born-again period, it's OK for Paul Simon to "introduce" his audience to reggae, to "world music," but it's somehow inauthentic for Joni - the Joni of "Big Yellow Taxi," "California," et al. - to step into more diverse sonic waters. As is the case with any artist interested more in art than success or notoriety, which is to say the kind of artist that is always moving forward, learning, developing their craft, there's always risk, and there's always pushback.

And then there's the case of Bob Dylan, whom she considered for a while her peer and "pace-setter," and with whom she toured, played, sang. Dylan, of course, constructed an entire identity for himself - one that more closely conformed to the folkie identity he was trying to cultivate - only to become the "voice" of a generation. And the mythos that developed, the way his songs seem to carry so much weight and found so many homes in so many hearts, went unchallenged. In a 2010 interview with the LA Times, Mitchell pushed back: "Bob is not authentic at all: He's a plagiarist and his name and voice are fake...We're like night and day." There's truth to it, of course - Dylan did in fact plagiarize his Nobel Prize in Literature lecture, and you could argue he's always wearing a mask in his lyrics - but, in part at least, this bitterness seems to be that he was praised for things she was not really "allowed" to do. Just ask Joan Baez.

But the thing is this: if there's anyone who always seemed above the fray it's Joni. Or maybe that's just another simplification, another case of projection, a composite rendered after decades in and out of the limelight, on and off stage, in record after record. A figure like this is far more than the men she loved, hated, was compared to, wrote about, served as muse to, and certainly more than the men who wrote about her. She's more than a brainy bard for the generation that wanted to build a utopia, but only managed to buy a back yard (the one that did indeed "pave paradise"). She's of course more than the strident remarks and praise of the male critics who described her changing outfits, who noted her cheekbones, who held her up to impossible standards. She never was any of those things - no matter how much audiences, lovers, and critics wanted to hold onto her, define her, she resisted such definition; she was never anybody's but hers. The Joni Mitchell we get - the one she chooses to reveal - is the one we sit beside as we put our earphones on and press play.

Copyright protected material on this website is used in accordance with 'Fair Use', for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner(s). Please read Notice and Procedure for Making Claims of Copyright Infringement.

Added to Library on January 8, 2023. (2141)

Comments:

Log in to make a comment