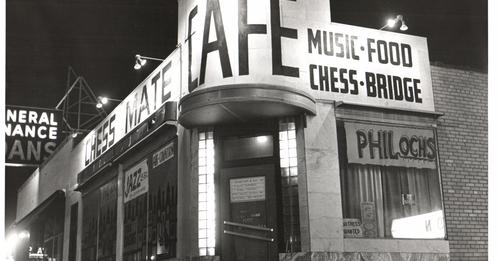

It's a Detroit laundromat now.

But back in the 1960s, its cinder-block walls - and eccentric, chess-master owner - hosted intimate, dimly lit, smoke-filled concerts with future music legends like Joni Mitchell, who at 21 was just coming into her own as a songwriter.

"The Chess Mate was really a proving ground for me," Mitchell told an interviewer in 1969.

A 1964 clipping from the Detroit Free Press discussing Morrie Widenbaum's Chess Mate Gallery.

Today, the building along Livernois Avenue, north of McNichols near the University of Detroit Mercy campus, holds dryers and washers, but no hint of its place in music history and no mention of Muddy Waters, Gordon Lightfoot, Taj Mahal, Doc Watson, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Howlin' Wolf and the carnival of others who performed there.

When Morrie Widenbaum opened the Chess Mate in 1963, it was literally a chess club. Widenbaum was Michigan's chess champion, and he envisioned an enriching, art-filled environment with soft jazz playing and chess lovers competing at tables throughout the room.

But chess couldn't pay the bills, not even with U.S. champion Bobby Fischer visiting in 1964 to take on 51 players simultaneously. So Widenbaum focused on music.

His no-alcohol coffeehouse drew Greenwich Village regulars and Bob Dylan contemporaries like Dave Van Ronk, Phil Ochs, John Hammond Jr. and Jim & Jean. Older blues artists John Lee Hooker, the Rev. Gary Davis and Jesse Fuller frequented the club, as did two groups that venerated them, Siegel-Schwall and Paul Butterfield, whose shows drew the future Iggy Pop.

Emerging artists appeared at the 200-capacity venue early in their journeys: Linda Ronstadt with the Stone Poneys, Richie Havens and Spanky and Our Gang prior to their hits, Jerry Corbitt and Jesse Colin Young - reborn as the Youngbloods - and Don Williams of Pozo-Seco before his Country Music Hall of Fame career.

And Neil Young.

Though he never headlined at Chess Mate, Young played a hootenanny - while outside, thieves rendered his car inoperable. Afterward, waiting for assistance, he wrote "The Old Laughing Lady" on a napkin at 4 a.m. in the White Tower burger joint kitty-corner to the club.

Joni knew Young from Canada. At a show in Winnipeg, he asked her to listen to "Sugar Mountain." The song so touched her that, in Detroit, she responded by writing "The Circle Game."

Some nights, Young stayed with Joni and Chuck Mitchell in their three-bedroom, fifth-floor walkup in the Verona at Ferry and Cass, across from Wayne State. Joni had married Chuck, a Michigan troubadour, in 1965.

The Mitchells' place became a sanctuary for touring folkies, like Lightfoot and Ramblin' Jack Elliott, who could save a few bucks on motels while enjoying the company of fellow musicians.

Though a duo, Joni and Chuck differed in style, entertaining both separately and together. They soon were being billed as "Detroit's favorite folk singers." Joni sang her own compositions and covers like the Beatles' "Norwegian Wood." Chuck offered greater variety.

Joni logged more than 60 Chess Mate performances within 12 months, most with Chuck. Sometimes, she opened or subbed for headliners.

"You could see her excellence," Muruga Booker said in a recent interview.

No one played the club more than Booker, then known as Steve, who ran the house band, provided high-energy drum solos between headliners' sets and led the 2-6 a.m. weekend jazz and blues jams.

Booker lives in Ann Arbor. He keeps memories of the Chess Mate alive, reminiscing of his five-hour, until-dawn drum battle with Roy Brooks, of blues man Sam Lay flashing his derringer, of Ted Nugent and Jim McCarty dropping in, of his overnight parties at the club fueled by "weed, acid and wine" and a tripping desire for "consciousness."

"The whole Woodstock generation was expressed through the Chess Mate," said Booker, who backed Tim Hardin at Woodstock and recorded with Dylan, Weather Report and George Clinton. "Morrie recognized the multiplicity of music. Real jazz, real blues, real rock, real folk. He allowed the '60s to be the '60s."

Widenbaum was quirky, a chess genius who could defeat 12 people at once while blindfolded. Songwriter Tom Rush described him in a 1998 interview as a brilliant, "strange fellow" who wore expensive, unhemmed pants and "couldn't tie his shoes."

Esther Widenbaum, his Israeli wife, handled employees and the cash register. Morrie's father, Isaac, a jeweler and Holocaust survivor, was a gregarious presence, charming patrons.

Linda Novetsky Mendelson worked at the club through college. Her mother and Widenbaum were cousins.

"Morrie just kind of floated by you," she said late last month.

Mendelson lived next to Stevie Wonder in northwest Detroit, so Chess Mate entertainers did not awe her. She remembers Joni Mitchell as standoffish and business-oriented, but polite. She preferred Phil Ochs for his personality and leftist politics. Ochs hung around after concerts and had a beer.

"It would be like 1 in the morning," she said. "He'd grab a napkin and start writing. I couldn't kick him out. He'd push the napkin over to me and say, 'What do you think?' It would be lyrics. This was someone unlike everybody else. Phil was so approachable, so down to earth, and his music spoke to me personally."

Mendelson loved that the Chess Mate brought people together: teenagers, college professors, their students, music lovers, hippies and, yes, aspiring musicians.

Before YouTube, "you had to go to the live shows, watch the hands of the players you admired and try to copy their chops, or get them to show you how," Chuck Mitchell said recently in an email interview. He played the club before, during and after his marriage to Joni.

It "was a big part of my life," he said.

He recalls Widenbaum fondly.

"He was equally adept at pool and poker," said Mitchell. "Story was he won back a good chunk of the money he paid to some of the bands ... before they packed up and left town."

In 1966, Widenbaum stumbled upon one of his biggest draws, the Blues Magoos. The long-haired, psychedelic rock band from New York City came for a week at a Redford lounge but got fired the first night. Widenbaum allowed them to rehearse in his club, and then hired them.

The band's youthfulness attracted exuberant teenagers. Among those who saw them was high school rocker Suzi Quatro, who told "Classic Rock" magazine this year they were "the first live band that I really loved."

Their album "Psychedelic Lollipop" charted, then their single "(We Ain't Got) Nothin' Yet" broke big. They toured with The Who and Herman's Hermits and appeared on American Bandstand. Still, in 1968, they returned to the Chess Mate for a final visit.

"We owed Morrie," said Castro. "He gave us a home there."

Regional acts like Ted Knight and Southbound Freeway brought crowds, too, as did Shakespearean actor Cedric Smith from Stratford. Some groups' names evoked the era: The Human Beings, Children of Paradise, Holy Modal Rounders, New Lost City Ramblers and Hello People, an anti-war country-rock group dressed as mimes.

The club survived competition from The Living End (with its liquor license), The Raven and The Retort. It endured the 1967 rebellion, and it persisted after the departure of Joni Mitchell (first to another club, and then from Chuck and Detroit).

Those factors, changing times, health issues and the early death of Esther Widenbaum prompted Widenbaum to close the Chess Mate in 1971. He died a year later, at age 46.

"There isn't another place like it," said Mendelson. "When we go by now and see a laundromat ..."

Noted Booker: "It's a place that needs to be remembered."

Tom Stanton, an associate professor of journalism at Detroit Mercy, is author of “Terror in the City of Champions.”

Copyright protected material on this website is used in accordance with 'Fair Use', for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner(s). Please read Notice and Procedure for Making Claims of Copyright Infringement.

Added to Library on July 11, 2021. (5732)

Comments:

Log in to make a comment