Interview: Transcribed by Greg Roensch.

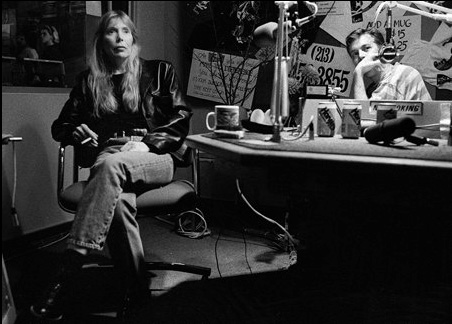

Chris Douridas: ... with Joni Mitchell and her new release, Night Ride Home.

Joni Mitchell: (singing)

CD: The title piece from Joni Mitchell's 16th collection of songs, Night Ride Home. I'm Chris Douridas. This is Morning Becomes Eclectic. And with me is Joni Mitchell. Thank you for coming by.

JM: Oh, you're most welcome.

CD: How's your voice doing?

JM: It's a little creaky.

CD: A little creaky.

JM: A little froggy.

CD: Taking a cue from one of the interviews that I had seen of yours, I was going to ask you, so what it is like to be a singer, Joni Mitchell?

JM: What was it like to be a singer?

CD: It must be irritating for you to see various critics trying to put your career in a circular sort of pattern rather than appreciating it for the forward-moving direction.

JM: Well, mostly critics get things wrong. Very seldom do you see anything correct actually. I think in America, here, music, and it's getting kind of worse if you don't mind me being so critical, is almost limited to the decade that you ripen in, so to speak, that you come into your teens. People cling to that era of their music, and that's their music. And, as a result of that, people tend to say, "Oh, back in your era," whereas in fact I've been active all this time. I feel very much a part of every era that I live in because I'm living in it, you know?

CD: Yeah.

JM: There is a kind of a circle here in a way that I will admit to. And that is that the record Hejira, which means going away from or running away with honor, so to speak, leaving the dream, was a departure from a time period which was potentially very positive for the brotherhood of man. There were a lot of good ideas that were hip. Many things were valued that were wholesome and healthy, and that declined into a period of apathy which was the 70s, and then flowered into that nasty black-coated greedy period which was the 80s. And now, coming into the 90s, I feel that there is, in myself and others, a desperate almost desire to reinvent this decade. Certainly we don't want to go along the same course that the last one took.

The 90s look like a fresh sheet of paper to me, and I approach them with a kind of an optimism, kind of a burgeoning, flickering, little, fragile light appeared. And I think that this album maybe reflects it. And some people have seen it as if Hejira was a going away from, this is a returning to, and I think there's an element of truth to that. The 80s were the antithesis of intimacy and romance. These are two of my functions. I couldn't really do it in the 80s, there was no point. It was too streamlined and glassy and chrome-plated. In the 80s the name of the game was win at any cost. Anyone who had a few marbles, the name of the game was to get them. You had hostile takeovers and hostile press, and hostile was very sheik. I mean Joan Collins, Dynasty, the bitch is back. This was all very important in the 80s.

(singing)

CD: "The Windfall" from Joni Mitchell's latest Night Ride Home. Joni Mitchell is my guest. I'm Chris Douridas. This is Morning Becomes Eclectic on KCRW. If it's okay with you, I want to back up just a bit and get a glimpse of you before you were Joni Mitchell, growing up in Canada, Roberta Joan Anderson.

JM: Oh, it was never Roberta except on my passport.

CD: Just on the birth certificate?

JM: Yeah.

CD: So it was always Joan Anderson growing up in Canada?

JM: Well, I was supposed to be a boy you see, and they had everything prepared for a Robert John. And it was quite a shock when I arrived, so they just added A's to it.

CD: So growing up and becoming Joni Mitchell, were there two selves?

JM: Two selves?

CD: A personal self, Joan, and a public self, Joni?

JM: Let's see, how would I describe myself? I had a lot of childhood illness and we moved around a lot, and I was an only child. You take those three elements and you get a loner pretty quick. So I grew up quite independent. My mother, when she reflects on how she raised me now thinks God she gave me way too much freedom. I used to go downtown and hang out on the streets. I always liked interaction with merchants. And I liked being on the street in an adult world of commerce for some reason. A gypsy once told me that I was an Arab rug salesman in another life. Maybe this is true.

I was a chatty kid and curious about things and liked talking to people. But I had difficulty playing with children my own age. The children in the communities that we lived in were pretty rough, I would say ... sticks and stones, and mostly the preoccupation on the playground was with athletics. And being sickly, although I was given a strong body, certainly strong enough to fight off all these diseases that I've had to come through, it set me back socially in a certain way. And so I would say that repeated childhood disease developed in me an inner life and a joy of creativity, which was necessary to fight some of these battles against bugs also to get your spirit up to survive. And that made me kind of even more different because there weren't many artists.

This was not a community really that produced artists. It had some pretension to classical music and there were a lot of children who studied voice, piano, some instrument. That was quite common in the town. I wanted to compose at an early age. That was uncommon in the town. As a matter of fact, it was kind of ridiculed and discouraged. The concept was, "Why would you want to invent music," that was called playing by ear, "when you could have the grand masters under your fingertips? You should study and become a classical musician and play Mozart and Brahms et cetera."

And I had, as my best playmates, two boys who were baby classical musicians. One could at a very young age, seven or eight, play the big pipe organ in the church. His feet could hardly reach the pedals but he could play quite elaborate pieces of music on it. And the other is now an opera singer somewhere in Italy. And our play consisted frequently of Frankie at the piano and Peter singing, and me leaping around the room. I was going to be a ballerina, the singing job was filled. And I had a lot of childhood friends, Sharon Bell, who I wrote a song for once, "Song for Sharon Bell."

The irony of that was I always saw myself married to a farmer because my favorite times really were to wander by myself or ride my bicycle as far as I could out into the country, which was always very close, looking for a beautiful place, which usually meant a tree. Because on the prairie it was bald and flat. Maybe just wander across the prairie feeling the wind on you, which is very strong, and big clouds. I think Neil Young's music and my music reflect that prairie lope, that stride, that we have a kind of a lope that is a flatlander's lope. I always think I hear it in his music too. So I thought I would marry a farmer. She ended up marrying a farmer and I ended up being a singer, and I wrote a song about that once.

CD: Growing up in a small town like that, how did you find the music that really broadened your horizons?

JM: Well, the first record that I fell in love with, the first piece of music, I think the piece of music that made me want to be a musician was in a movie starring Kirk Douglas. It was called "The Story of Three Loves." And there was a piano, I guess a sonata form, I'm not really sure, but featuring a piano, a beautiful melody by Rachmaninoff called "Variation on the Theme by Paganini." And I'd gone with Frankie, the kid who was this piano protégé friend of mine. And at that time there was no rock and roll. There was very little rhythm and blues on the radio where I came from, mostly country and western, classical, semi-classical, the McGuire and the Andrews sisters, Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby. It was that era. Harry James. I'd listen to it and I'd have literal sleeping dreams that I was sitting at the piano and my fingers were moving across and beautiful melodies were coming out. I alternated those with dreams that I could drive a car. It was like...

CD: Oh, yeah, yeah.

JM: ... my two great longings... and finally I persuaded my parents, we were quite poor, convinced them that I really had to learn to play the piano. And so we bought a piano off the back of a truck. It came in the winter. And there was a ramp, and it went up the ramp in the back and just spin it out of the collection. And I proceeded to take piano lessons from Miss Traleven, who was a very severe woman, who said I played by ear and wrapped my knuckles with a ruler. And that kind of killed the love of composition for about, I don't how long it would be, 10 years it knocked it out of me.

CD: Miss Traleven?

JM: Miss Traleven.

CD: Miss Traleven.

JM: And Miss Traleven played duets with my father who was a Harry James wannabee.

CD: He played trumpet?

JM: He played classical trumpet.

CD: Wow.

JM: And they played together. And I think she had a crush on him, I'm pretty sure. She resented both my mother and I.

CD: When did Edith Piaf come along?

JM: I heard Edith Piaf at Helen La Franeer's eighth birthday party. Helen was French. And just as the pink cake was coming out of the kitchen, Edith Piaf came bubbling up through the background voices of Les Compagnons de la chanson. And all my hair on my arms stood up on end. And I asked Helen's mother who that was. And she was tiny and frail and she said to me, "Oh, that was the little sparrow," she said. And I remember thinking that she looked like a little sparrow.

(singing)

That always was the voice. I don't know, I'd never heard... until I heard Billie Holiday, I don't think a female singer ever affected me in that way. A lot of male singers but most women... She made everyone sound like a cheerleader somehow, I don't know.

CD: It's odd because I came into your music through Mingus, the Mingus album, which was supposed to be a collaborative work, I understand, between you and Charlie Mingus.

JM: It was really his project. He sent for me. We put it on my label thinking, because I sold more units, that it would give him a bigger funeral, so to speak. Little did we know, no one would have it.

CD: Did that really come up? That's really something you guys discussed, that it would...

JM: Not directly, but he did say to me that after Donovan wrote Mingus Mellow Fantastic, that people noticed him on the street going by with his bass, whereas prior to that they didn't. So, yeah, he was a bit infatuated with having a broader recognition that the pop association perhaps would give him.

CD: Do you think that your path might have been different had he lived?

JM: Gee, I don't know. It's hypothetical. In what way? I mean...

CD: I don't know, suppose that the album had been more of a collaborative work and suppose that... Did he die in the middle of the recording?

JM: Well it couldn't have been more of a collaborative work because I'm impossible to collaborate. In a way, Charles had the broadest emotional range of any person I ever met. He cried easy. He was very sensitive. He was very bright. He was very pure. He had a very fine jive detector. And he was offended by false emotion in music. Well, that's a blessing and a curse because most music has a lot of false emotion. Most people don't notice the difference. Charles was painfully aware of it and from time to time would punch one of his players out right on stage for falsifying his emotion. If he would go off his center and preen a little too much... And I guess that in certain moods Charlie was more generous to that kind of display, peacockery. But towards the end he didn't really like much of his record. The records that he'd left, he liked one, and I can't remember the name of it, and some Charlie Parker. But most of the time he'd sit around and listen to things going, "That's the wrong mood. That ain't shit. They're falsifying an emotion. That's jive. Who cares."

So to work with him, it was an experience because, for one thing, Charles was prejudiced against electrical instruments. I'd been through that once in the coffee houses when Dylan plugged in. It seemed a silly line of distinction, a silly divisionalism to me. And I did believe that the best bass player on the planet at that time was an electric player, Jaco Pastorius. And it was he that I wanted to make this music with. Charles had me try every acoustic player on the planet, great, great, great acoustic bass players, but in my mind it was always Jaco. Jaco was the progress, he was the one that was moving forward. And Charles, every time I'd... I played with a lot of different bands making that, trying to please him, trying to please him. And I'd come back, "How'd it go?," he said. I said, "Well." I'm reluctant to tell him. These are great musicians but for one reason or other, what they had for dinner that day, what their wife said to them before they left, they're too thin, they're too fat, whatever the distraction was, they didn't play forward enough for me. They were playing Dixieland. They were retro. They were playing... I wanted to move forward, even though it was kind of a foreign idiom to me. I'd absorbed a lot of jazz, but I'd never made it.

I mean so he'd say, "Well, how'd it go?" And I'd go, "Well." And he'd say, "He plays too notey, don't he?" He always knew what the problem was, as good as these people were. But as for going on in that, I'm not sure. Charles heard some of what I did but he wasn't... He was very pleased with the lyrics and he was pleased with my singing. Although "A Chair in the Sky," for instance, I made a demo which I sang. When I sang it, I didn't think about anybody but him. But I made some wrong notes, I made some mistakes where I deviated from his melody, because he was a stickler. I improvised a note here and a note there. And I thought, "Oh, I got to stick to the melody here for him." Take two, I sang to him and the piano player and the engineer. Now this was a very subtle thing, most people would never perceive this. Well wrong notes and all, when the tape went to him, take one and take two, it was like a letter, Charles said, when he heard these mistakes that ordinarily he would be violent about, I changed his melody, he said, "It should've gone to the moon."

He was able to perceive it was as pure as the letters between Vincent and Theo. They were not meant for the world to read. Take two, the singing was actually technically a little better and I stayed in this structure that he had given me, but he didn't care. So the beauty I think of Charles was that he could really see pure spirit and the nuances as it deviates into intellectualism and the hundred and other deviations that most musicians deviate into. He could actually see these things. And that's a real curse.

(singing)

CD: "A Chair in the Sky" from Mingus, music by Joni Mitchell and Charlie Mingus. Joni Mitchell is my guest. I'm Chris Douridas. This is Morning Becomes Eclectic on KCRW. Joni, with worldwide communications at an all-time high, the continents are getting closer together, and I always think it's odd that we think in terms of borders and we isolate ourselves and such. But you poked through those borders in 1976 on Hissing of Summer Lawns with "The Jungle Line," borrowing a drum track from Burundi in Central Africa. Did you consider bringing the musicians over for that recording?

JM: I didn't even know they were alive. I finally saw them play in England. I attended a concert where they played. And there was some press there and they came up behind me and said, "Have you ever heard this music before?" I said, "That's my band. I've played with these guys." It was great to see it visually because there's a wood sound and a skin sound. And in my mind, when they hit the wood sound, I saw them all in a line clicking these big, wooden sticks together side by side, more like spear clinking. So to see it and them actually play was very, very, very interesting.

And that stood out to me as just some of the greatest rock and roll I ever heard. And I said to Henry, the engineer, that I worked with at that time, "Henry, I love this thing. There's a Bo Diddley lick in here. It's kind of like a Bo Diddley. Let's make a loop. So, I go, "Cut it there!" I mean I'd be tapping it but I couldn't give him a smooth, numerical communication on it. So it came out a little longer, not as symmetrical as I would like. And as a result, you get these random whoops coming up all the way through.

(singing)

CD: "The Jungle Line" from Hissing of Summer Lawns, Joni Mitchell with drummers from Burundi on tape loop. Joni Mitchell is my guest. I'm Chris Douridas on Morning Becomes Eclectic. This is KCRW. Bridging the cultural gaps like you did on Jungle Line, one thing that we all have in common no matter what culture we come from is we're all watching the clock. Time is ticking away. Time is one thing that we can rely on to be constant. On your new release, Night Ride Home, there's a resigning statement of life passing by, time passing by, nothing can be done.

JM: Surrender gracefully the things of youth. This is not a culture that surrenders gracefully the things of youth, and it condemns its old age really to imprisonment of a sort. To be putting on your brakes as you hit middle age, especially for us, the war babies, we're a big population curve. There's going to be perhaps this predictable sociological consequences of all of us going gray at the same time.

CD: Yeah, and in fact the marketing is already starting to shift to senior citizens.

JM: How can we exploit them? They already send buses to the old-age homes near Atlantic City on the day the old-age checks come. And of course you've got the evangelists up there appealing to little old women close to death.

(singing)

CD: This is Morning Becomes Eclectic on KCRW. Joni Mitchell is my guest. And funny... we were just painting lips here. And I was just thinking that I've seen one painting of yours at Hal's Bar & Grill in Santa Monica. It was the first time I had seen a painting of yours that wasn't on an album cover. Do you find that as a painter you release some ideas that you weren't able to release in song?

JM: Most of what happened, and I think the best of the art happened at the break in this century, a lot of it is very derivative. I mean Picasso uncovered most of the major secrets. I mean he's very rock and roll. The primitive African meets the sophisticated European, so to speak, just like rock and roll. As a painter, I'm not ambitious, thank god. I don't have to exploit it. I can keep my desire to paint pure and simple like Van Gogh. If he wants to paint his red chair and his blue room, fine. Whereas I think people working today as artists have a hard time breaking in now because we're drowning in images. We're drowning in images. So to be outstanding in this mire of substance, shock has become the king. You have to shock your way out. You have to be outstanding in that manner, and conceptual. And it's so far away from painting. I'm just a simple painter. If I see my husband sleeping and the cat is sleeping around his chin, I'll paint that. I don't have to think whether, "Ooh, is it sentimental or is it important in today's context?" So I'm spared all of the art nonsense. And I just paint because I want to.

(singing)

CD: "The Only Joy in Town" from Night Ride Home, Joni Mitchell's latest release on Geffen Records. I'm Chris Douridas. This is KCRW's Morning Becomes Eclectic. Joni Mitchell is my guest. It's very rare that the poetry of William Butler Yeats is allowed to be used in song. This album has it. I understand that his estate is keeping a really close watch on what's happening with his poetry.

JM: They were difficult. Generally speaking, they don't release his poems except to classical music, to what they consider serious composition. So there was kind of a painful wait to see if they'd deem this classical enough for them.

CD: When you actually were putting the song together, did you originally put it together as the original poem and then come back to it?

JM: Oh no. No, the original poem was not in my mind in singable form. It looked to me like he had never finished it. "Turning and turning within the widening gyre, the falcon cannot hear the falconer," that's beautifully constructed writing. The second stanza looked almost like a first draft. And at the time, I suppose, blank verse was quite fashionable, and abstract painting and first gesture. Perhaps it was the influence, the modernness of the time that kept him from finishing it. Scholars will come after me for this, "How dare you say that it was unfinished," but it was a verse of poetry and a verse of more like prose. Even the layout of it.

(poem being read) "Turning and turning in the widening gyre, the falcon cannot hear the falconer. Things fall apart, the center cannot hold. Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, the blood-dimmed tide is loosed. And everywhere the ceremony of innocence is drowned. The best lack all conviction while the worst are full of passionate intensity."

JM: It was an idea that I couldn't sing because I couldn't buy it. It kept flopping over, "The best lack all conviction and the worst are full of passion." Well I thought of innocence as when the opposite was true and when the best were full of passion and the worst lacked all conviction. So to me it was an unstable idea. And to stabilize it I put it in a setting of qualification, "The best lack all conviction, given some time to think, and the worst are full of passion without mercy." So I interpreted it a little bit to enable me to sing it with conviction.

(singing)

CD: "Slouching Towards Bethlehem," that's from Night Right Home, Joni Mitchell's latest effort on Geffen Records. This is KCRW's Morning Becomes Eclectic. I'm Chris Douridas, and with me is Joni Mitchell. I want to thank you so much for coming by. Will you be still writing and singing in the years ahead? Do the albums come when you have something more to say or are you prolific in that you are constantly writing?

JM: Well, for most people it gets harder and harder to be prolific. I think as you get older things become less profound. You enter into an epic period and things repeat. And if you can still see the nuances in them, then you shouldn't dry up. A lot of people do. The question is, you stay in this business if people vote for you. It's a democratic system. As long as my records sell, I have a contract. If they don't sell, I have no contract. But if all failed, I would be quite content to be a painter. That's a dignified career for the middle years and on.

CD: Well, we don't want to lose you because you're sounding more and more like Edith Piaf.

JM: Yeah, just when you're getting to that place, exactly.

CD: Thanks so much for coming by.

JM: Oh, you're very welcome.

CD: Appreciate it.

JM: I never get up in the morning like this.

(singing)

CD: Listening to Joni Mitchell from Night Ride Home, "Come in from the Cold." Thanks to Joni Mitchell for coming by. She was recorded by Jerry Summers last week. My thanks to Geffen records and to Gloria Boyce and to Ariana Morgenstern. I'm Chris Douridas. We continue Morning Becomes Eclectic on KCRW Santa Monica. Coming up in about 20 seconds, a news update from National Public Radio.

JM: (singing)

Copyright protected material on this website is used in accordance with 'Fair Use', for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner(s). Please read Notice and Procedure for Making Claims of Copyright Infringement.

Added to Library on December 5, 2019. (3258)

Comments:

Log in to make a comment