A tiny coffeehouse-folk club in Toronto's Yorkville district was one of the mid-sixties settings for the launching of Joni Mitchell's spectacular career. She began singing in her hometown Saskatoon, and had created a minor stir at that summer's Mariposa Folk Festival. Even so, when she applied for a full-time job as an entertainer at the little folk club known as the Riverboat, owner Burnie Fiedler said there was an opening only for a dishwasher.

That was nearly a decade ago, and a lot of changes have gone down since. Fiedler, for instance, is now an old friend, and Joni Mitchell today is a recognized superstar, perhaps the only songwriter to have songs recorded by both Bob Dylan and Frank Sinatra. Nevertheless, it was at the Riverboat where Malka first met Joni Mitchell. The Israeli-born singer had gone to catch her performance because, like everyone else in the Toronto folk scene, she had heard of the new young talent that had recently arrived from the west. Malka was much impressed, particularly with a song called Both Sides Now, the tune that eventually sold a million copies for Judy Collins.

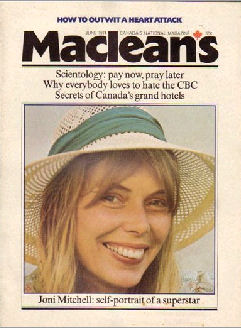

The following, then, is a part of a long conversation between two singers who since have left the life of performing night after night in small folk clubs. Malka has branched out into broadcast journalism, and is a regular contributor to the CBC radio program, "The Entertainers;" as well, she does concerts and sings on radio and television specials. The interview—the first given by Joni Mitchell in several years—took place just prior to the recording artist's now completed North American concert tour, and just after her thirtieth birthday. It was the first meeting between the two women since the days when folk music reigned supreme in Yorkville.

Malka: You're on the road performing again. Why the silence of two full years?

Joni: I like to retire a lot, take a bit of a sabbatical to keep my life alive and to keep my writing alive. If I tour regularly and constantly, I'm afraid that my experience would be too limited, so I like to lay back for periods of time and come back to it when I have new material to play. I don't like to go over the old periods that much; I feel miscast in some of the songs that I wrote as a younger woman.

Malka: How do you feel, then, about listening to your records?

Joni: I don't enjoy some of the old records; I see too much of my growing stage; I've changed my point of view too much. There are some of them that I can still bring life to, but some that I can't. Let's take the LADIES OF THE CANYON album; there are good songs on there which I feel still stand up and which I could still sing. There's a song called The Arrangement which seemed to me as a forerunner and I think has more musical sophistication than anything else on the album. And the BLUE album, for the most part, holds up. But there are some early songs where there is too much naivete in some of the lyrics for me to be able now to project convincingly.

Malka: Your name has been linked to some powerful people in the business, James Taylor and Graham Nash, for instance. Do you feel that your friends have helped your career in any way?

Joni: I don't think so, not in the time that James and I were spending together anyway. He was a total unknown, for one thing—maybe I helped his career?...But I do think that when creative people come together, the stimulus of the relationship is bound to show. The rock and roll industry is very incestuous, you know, we have all interacted and we have all been the source of many songs for one another. We have all been close at one time or another, and I think that a lot of beautiful music came from it. A lot of beautiful times came from it, too, through that mutual understanding. A lot of pain too, because, inevitably, different relationships broke up.

Malka: But isn't there a certain amount of danger, when you surround yourself with musicians and troubadours doing the same kind of work you are doing, that you really create your own special world and are not so open to what's happening in the rest of the world?

Joni: A friend of mine criticized me for that. He said that my work was becoming very "inside." It was making reference to roadies and rock 'n' rollers, and that's the very thing I didn't want to happen, why I like to take a lot of time off to travel some place where I have my anonymity and I can have that day-to-day encounter with other walks of life. But it gets more and more difficult. That's the wonderful thing about being a successful playwright or an author: you still maintain your anonymity, which is very important in order to be somewhat of a voyeur, to collect your observations for your material. And to suddenly often be the center of attention was. .. it threatened the writer in me. The performer threatened the writer.

Malka: When you were a little girl, did you think that you would be a singer one day, or a songwriter? How did it all start?

Joni: I always had star eyes, I think, always interested in glamour. I had one very creative friend whom I played with a lot and we used to put on circuses together, and he also played brilliant piano for his age when he was a young boy. I used to dance around the room and say that I was going to be a great ballerina and he was going to be a great composer, or that he was going to be a great writer and I was going to illustrate his books. My first experience with music was at this boy's house, because he played the piano and they had old instruments like auto harps lying around. It was playing his piano that made me want to have one of my own to mess with, but then, as soon as I expressed interest, they gave me lessons and that killed it completely. My childhood longing mostly was to be a painter, yet before I went to art college my mother said to me that my stick-to-itiveness in certain things was never that great, and she said you're going to get to art college and you're going to get distracted, you know. Yet all I wanted to do was paint. When I got there, however, it seemed that a lot of the courses were meaningless to me and not particularly creative. And so, at the end of the year I said to my mother I'm going to Toronto to become a folk singer. And I fulfilled her prophesy. I went out and I struggled for a while.

Malka: Did you ever think you'd make it so big?

Joni: No, I didn't, I always kept my goals very short, like I would like to play in a coffeehouse, so I did. I would like to play in the United States, you know, the States, the magic of crossing the border. So I did. I would like to make a certain amount of money a year, which I thought would give me the freedom to buy the clothes that I wanted and the antiques and just some women trips, a nice apartment in New York that I wouldn't have to be working continually to support. But I had no idea that I would be this successful, especially since I came to folk music when it was already dying.

Malka: Many of your songs are biographical — do you think that the change in your lifestyle now has affected your songs?

Joni: I don't know. I had difficulty at one point accepting my affluence, and my success and even the expression of it seemed to me distasteful at one time, like to suddenly be driving a fancy car. I had a lot of soul-searching to do as I felt somehow or other that living in elegance and luxury canceled creativity. I still had that stereotyped idea that success would deter creativity, would stop the gift, luxury would make you too comfortable and complacent and that the gift would suffer from it. But I found the only way that I could reconcile with myself and my art was to say this is what I'm going through now, my life is changing and I am too. I'm an extremist as far as life-style goes. I need to live simply and primitively sometimes, at least for short periods of the year, in order to keep in touch with something more basic. But I have come to be able to finally enjoy my success and to use it as a form of self-expression, and not to deny. Leonard Cohen has a line that says, "do not dress in those rags for me, I know you are not poor," and when I heard that line I thought to myself that I had been denying, which was sort of a hypocritical thing. I began to feel too separate from my audience and from my times, separated by affluence and convenience from the pulse of my times. I wanted to hitchhike and scuffle. I felt maybe that I hadn't done enough scuffling.

Malka: But success does have some rewards. The Beatles, for instance, before they disbanded translated it into a movement for peace. How do you think it affected you, the success?

Joni: In a personal way it gives me the time to be able to pick and choose my project, to follow the path of the heart, which is really a luxury. So that I can be true to myself. I know a lot of artists who don't have that freedom, friends of mine who are still struggling to buy themselves that independence. Then there comes the question of do you take it all for yourself or what do you put back into the world? I haven't really found what I am to do. People are always coming up with great causes for me to get involved in and they have wonderful arguments and reasons why I should be. The ones I select are the ones that I am genuinely interested in because I feel that they will show some sort of immediate return. Maybe this is impatience, like in the Greenpeace, we raised some money to buy the ship which went to Amchitka with the hopes that they were going to sit in the territorial waters in this area where they're exploding bombs ridiculously close to the San Andreas fault. That inflamed me. That was a project I wanted to be a part of. In Montreal I played at a benefit for Cree Indians who were being displaced by a very stupidly run dam project. I know that money can be put to positive use, even if it's just to support people struggling in the arts. I believe in art, I believe that it's very important that people be encouraged in their self-expression and that their self-expression Ping-Pongs someone else's self-expression. That's what I believe in the most. If I'm going to distribute some of my windfall it would be among other artists.

Malka: Do you consider yourself a Canadian, Joni?

Joni: I definitely am Canadian. I'm proud of that and when it came to settling the place where I decided I wanted to spend my old years, I bought some property north of Vancouver.

Malka: You were once quoted as saying that your poetry is urbanized and Americanized and your music is of the Prairies.

Joni: I think that there is a lot of Prairie in my music and in Neil Young's music as well. I think both of us have a striding quality to our music which is like long steps across flat land. I think so, although I'm getting a little New Yorkish now with this jazz influence that's coming in. It's got to be urbanized. I talk about American cities, about Paris, about Greece, I talk about the places where I am.

Malka: On your new album, COURT AND SPARK, for the first time you've recorded a song that isn't yours, Twisted. Why did you decide to record something that is not your own?

Joni: Because I love that song, I always have loved it. I went through analysis for a while this year and the song is about analysis. I figured that I earned the right to sing it. I tried to put it on the last record but it was totally inappropriate. It had nothing to do with that time period and some of my friends feel it has nothing to do with this album either. It's added like an encore.

Malka: I hope I'm not encroaching on your privacy, but why the analysis now?

Joni: I felt I wanted to talk to someone about the confusion which we all have. I wanted to talk to someone and I was willing to pay for his discretion. I didn't expect him to have any answers or that he was a guru or anything, only a sounding board for a lot of things. And it proved effective because simply by confronting paradoxes or difficulties within your life several times a week, they seem to be not so important as they do when they're weighing on your mind in the middle of the night, by yourself, with no one to talk to, or someone to talk to who probably will tell another friend who will tell another friend as friends do. I felt that I didn't want to burden people close to me so I paid for professional help. And I went through a lot of changes about it, too. It's like driving out your devils — do you drive out your angels as well? You know that whole thing about the creative process. An artist needs a certain amount of turmoil and confusion, and I've created out of that. It's been like part of the creative force — even out of severe depression sometimes there comes insight. It's sort of masochistic to dwell on it but you know it helps you to gain understanding. I think it did me a lot of good.

Malka: When I listen to your songs I notice that there are certain themes that keep appearing, one theme that comes up often is loneliness.

Joni: I suppose people have always been lonely but this, I think, is an especially lonely time to live in. So many people are valueless or confused. I know a lot of guilty people who are living a very open kind of free life who don't really believe that what they're doing is right, and their defense to that is to totally advocate what they're doing, as if it were right, but somewhere deep in them they're confused. Things change so rapidly. Relationships don't seem to have any longevity. Occasionally you see people who have been together for six or seven, maybe 12 years, but for the most part people drift in and out of relationships continually. There isn't a lot of commitment to anything; it's a disposable society. But there are other kinds of loneliness which are very beautiful, like sometimes I go up to my land in British Columbia and spend time alone in the country surrounded by the beauty of natural things. There's a romance which accompanies it so you generally don't feel self-pity. In the city when you're surrounded by people who are continually interacting, the loneliness makes you feel like you've sinned. All around you you see lovers or families and you're alone and you think, why? What did I do to deserve this? That's why I think the cities are much lonelier than the country.

Malka: Another theme I think is predominant in your songs is love.

Joni: Love... such a powerful force. My main interest in life is human relationships and human interaction and the exchange of feelings, person to person, on a one-to-one basis, or on a larger basis projecting to an audience. Love is a peculiar feeling because it's subject to so much ... change. The way that love feels at the beginning of a relationship and the changes that it goes through and I keep asking myself, "What is it?" It always seems like a commitment to me when you said it to someone, "I love you," or if they said that to you. It meant that you were there for them, and that you could trust them. But knowing from myself that I have said that and then reneged on it in the supportive — in the physical — sense, that I was no longer there side by side with that person, so I say, well, does that cancel that feeling out? Did I really love? Or what is it? I really believe that the maintenance of individuality is so necessary to what we would call a true or lasting love that people who say "I love you" and then do a Pygmalion number on you are wrong, you know. Love has to encompass all of the things that a person is. Love is a very hard feeling to keep alive. It's a very fragile plant.

Malka: I sometimes find myself envying people that seem to be able to handle love, people who have found a formula for marriage. You were married at one point yourself how do you feel about marriage now?

Joni: I've only had one experience with it, in the legal sense of the word. But there's a kind of marriage that occurs which is almost more natural through a bonding together; sometimes the piece of paper kills something. I've talked to so many people who said, "Our relationship was beautiful until we got married." If I ever married again I would like to create a ceremony and a ritual that had more meaning than I feel our present-day ceremonies have, just a declaration to a group of friends. If two people are in love and they declare to a room of people that they are in love somehow or other that's almost like a marriage vow. It tells everybody in the room, "I am no longer flirting with you. I'm no longer available because I've declared my heart to this person."

Malka: Do you think you'll get married again?

Joni: I really don't know. I wouldn't see a reason for marriage except to have children, and I'm not sure that I will have children you know. I'd like to and I have really strong maternal feelings, but at the same time I have developed at this point into a very transient person and not your average responsible human being. I keep examining my reasons for wanting to have a child, and some of them are really not very sound. And then I keep thinking of bringing a child into this day and age, and what values to instill in them that aren't too high so they couldn't follow them and have to suffer guilt or feelings of inadequacy. I don't know. It's like I'm still trying to teach myself survival lessons. I don't know what I would teach a child. I think about it . . . in terms of all my talk of freedom and everything.

Malka: Freedom, and in particular the word "free," is another theme in your music. What does freedom mean to you?

Joni: Freedom to me is the luxury of being able to follow the path of the heart. I think that's the only way that you maintain the magic in your life, that you keep your child alive. Freedom is necessary for me in order to create and if I cannot create I don't feel alive.

Malka: Do you ever envision or fear that the well of creativity might dry up?

Joni: Well, every year for the last four years I have said, "That's it." I feel often that it has run dry, you know, and all of a sudden things just come pouring out. But I know, I know that this is a feeling that increases as you get older. I have a fear that I might become a tune smith, that I would be able to write songs but not poetry. I don't know. It's a mystery, the creative process, inspiration is a mystery, but I think that as long as you still have questions the muse has got to be there. You throw a question out to the muses and maybe they drop something back on you.

Malka: Sitting from the outside, it seems that as a creative person you have attained quite a lot: you have an avenue in which to express your talent, affluence, recognition. What are your aims now?

Joni: Well, I really don't feel I've scratched the surface of my music. I'm not all that confident about my words. Thematically I think that I'm running out of things which I feel are important enough to describe verbally. I really think that as you get older life's experience becomes more; I begin to see the paradoxes resolved. It's almost like most things that I would once dwell on and explore for an hour, I would shrug my shoulders to now. In your twenties things are still profound and being uncovered. However, I think there's a way to keep that alive if you don't start putting up too many blocks. I feel that my music will continue to grow — I'm almost a pianist now, and the same thing with the guitar. And I also continue to draw, and that also is in a stage of growth, it hasn't stagnated yet. And I hope to bring all these things together. Another thing I'd like to do is to make a film. There's a lot of things I'd like to do, so I still feel young as an artist. I don't feel like my best work is behind me. I feel as if it's still in front.

Copyright protected material on this website is used in accordance with 'Fair Use', for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner(s). Please read Notice and Procedure for Making Claims of Copyright Infringement.

Added to Library on January 9, 2000. (12924)

Comments:

Log in to make a comment