This article is part of a longer Joni Mitchell interview/profile that appears in Jeffrey Pepper Rodgers' book Rock Troubadours. For more info on the book, click here.

Joni Mitchell is one of those rare songwriters whose music is created from the

ground up. Her signature as a composer can be found not only in the melody and

lyric, but in the idiosyncratic chord movement, the expansive guitar and piano

voicings, and the chorus of supporting voices and instruments. In describing

her music, Mitchell often uses the language of painting, and, indeed, all of

these elements of her songs blend together very much like brush strokes on a canvas.

In Acoustic Guitar's August 1996 cover story, "My Secret Place", I profiled

Mitchell's radical guitar style, drawing on an interview conducted early last

year. But in truth, the guitar was only one touchpoint of our three-hour-long

conversation, and Mitchell's comments on alternate tunings sailed right into

thoughts on poetry and painting and the music business and then back to the

guitar again, without a pause or a break in the logic.

This article will take a second look inside Mitchell's music, through the lens

of the voice and lyrics. In discussing her slant on the lyric craft, Mitchell

recalled her days as an art student in Toronto, where she was performing music

on the side - mainly the English folk repertoire - but had not yet started writing

songs. "I didn't really begin to write songs until I crossed the border into

the States in 1965," she said. "I had always written poetry, mostly because

I had to on assignment. But I hated poetry in school: it always seemed shallow

and contrived and insincere to me. All of the great poets seemed to be playing

around with sonics and linguistics, but they were so afraid to express themselves

without surrounding it in poetic legalese. Whenever they got sensitive, I don't

know, I just didn't buy it."

Outside of school, Mitchell still found herself writing poems when a strong emotion hit

her; such as when a friend committed suicide. But it wasn't until she heard Bob

Dylan's "Positively Fourth Street" that she finally began to understand how to tap the

power of this private poetry in a song. She recalled, "When I heard that 'You've got a

lot of nerve to say you are my friend' I thought, now that's poetry; now we're talking.

That direct, confronting speech, commingled with imagery, was what was lacking for

me." Later, in the '70s, Mitchell found her ideal of poetry reflected In the words of

Friedrich Nietzsche's character Zarathustra, who envisions "a new breed of poet, a

penitent of spirit; they write In their own blood." She added, "I believe to this day that

If you are writing that which you know firsthand, it'll have greater vitality than if you're

writing from other people's writings or secondhand information,"

Thanks in large part to Mitchell's influence, personally based writing became one

of the emblems of the singer-songwriter movement that flowered in the '70s and is

going strong again in the '90s. Even today, her 1970 album Blue (Reprise - written and

recorded, she said, in a fragile state somewhere between nervous breakdown and

breakthrough stands as one of the most emotionally naked performances ever

captured on tape. The songs are unquestionably written in her own blood, and even

though she has progressed through many modes of writing since then some more

obviously autobiographical than others - her personal commitment to the words

always shines through.

The mixture of direct speech and more abstract imagery that Mitchell admired in

"Positively Fourth Street" remains a hallmark of her own writing.

Matching these different lyrical styles with the right sections of the

melody, she explained, is a matter of listening closely to the song as it

unfolds. "Sometimes the words come first, and then it's easier, because

you know exactly what melodic inflection is needed. Given the melody first,

you can say, for instance, 'OK, in the A section, I can get away with

narrative, descriptive. In the B, I can only speak directly, because of the

way the chords are moving. I have to make a direct statement. And in the C

section, the chords are so sincere and heartrending that what I say has to

be kind of profound, even to myself. Theatrically speaking, the scene is

scored - now you have to put in the dialogue.

"Also, it has to be married to the inflection of English speech," Mitchell

said. "Pop music doesn't carry this fine point very far, although a lot of

great simple songs do. You know, [sings] 'Yesterday.' That's a good melody;

that's a good marriage of words and melody, just that simple little piece."

To under-score the point, Mitchell sang another example. "OK, you sing:

"puts the emphasis on the word 'I'. You don't want the emphasis on the word 'I'

So a lot of times, even though I may have written the text symmetrically

verse to verse to verse, in terms of syncopation I'll sing a slightly different

melody to make the emphasis fallon the correct word in the sentence, as you

would in spoken English."

Throughout the interview, Mitchell described her vocal craft by using the

language of theater, just as she explained her sense of harmony In terms

of painting. Metaphorically, these art forms make a lot of sense together:

The chord movement is the painting of the stage scenery-the context and

structure of the music-and In the vocal parts, she steps onto the stage to

act out the part she has scripted for herself. Mitchell's goal as a singer,

like that of a good actor, is to embody the words and rise above what she

called the "emotional fakery" of pop music.

"Pop music in particular, but music in general, is full of falseness, just

loaded with it," Mitchell said. "Blessedly, most people don't hear it,

otherwise none of the stuff would be popular. It's contrived, false

sexualness in the voice, false sorrow in the voice." This quality is as

true of instrumental music as vocal music, Mitchell said, and she recalled

a conversation with Charles Mingus shortlv before his death in l979,

when they were collaborating on what became her Mingus album (Asylum).

"Mingus at the end, when I went to work with him, couldn't listen to

anything except a couple of Charlie Parker records. He kept saying [imitates

deep, raspy voice], 'That ain't shit. He's falsifying his emotions.

Pretentious mother fucker.' Charlie could hear it; I could hear it.

He couldn't stand to listen to most of his records

because he could perceive in the note the egocenteredness of a player.

It's not pleasant to have that perception."

Mitchell cited another example of the importance of the singer's attitude

and sincerity, from the sessions for her forthcoming album, the follow-up

to Turbulent Indigo (Reprise). "I'm doing these vocals," she said, "for

this song called 'No Apologies.' It's a heavy song. I've had to take four

passes at it because it's so heavy that if I color it with any attitude it

makes me want to get up and shut it off. I [have to] sing it absolutely

deadpan, because it's got such strong language in it."

Beyond the lead vocal, Mitchell often builds elaborate backup vocal parts-

usually her own voice multitracked many times over-that amplify or comment

on the lyrics in highly unusual ways. She traces this idea to her child

hood, when she sang in a church choir after recovering from polio. "I took

on the descant part, which I called 'the pretty melody,"' she said. "Most

people couldn't sing it because it jumped around too much. Most people-kids,

anyway, in a children's choir-couldn't hold onto a note much beyond a third

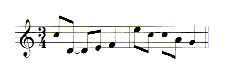

spread; these had five and seven and eight-note spreads [sings]:

"[The descant parts] wove all the tighter harmonies of the choral piece

together. So from there I got a very unusual melodic sense."

Mitchell considers some of her songs with complex vocal arrangements to

be, first and foremost, choral pieces. One example is "The Reoccurring

Dream" (from Chalk Mark in A Rain Storm, Geffen; also included on

Reprise's new Misses collection), in which background voices chant the

seductive messages of advertising: "Latest styles and colors!" "I want a

new truck-more power!" "More fulfilling- and less frustrating!" In "The

Sire of Sorrow (Job's Sad Song)," the masterful closing work of Turbulent

Indigo, the background voices are, according to Mitchell, "actually

characters-they're the antagonists. They have the insulting lines that

these so-called friends of Job's say to him. They augment the drama."

Another example of Mitchell's elaborate dramatic conceptions of her vocal

parts is "Slouching towards Bethlehem" (Night Ride Home, Geffen), in which

she adapted William Butler Yeats' famous poem "The Second Coming" and added

some new words of her own. In the background vocals, she said, "Conceptually speaking, I wanted it to sound like a global women's lament, so I

sang some of the backgrounds with the flatted African palate and some of

them with an Arabic kind of [sings warbling sound]. I set myself up

theatrical assignments like that. Whether or not I achieved that is

debatable. To me I did, but then I know what the concept was and what the

goal was; other people listening to it maybe think [the voices] are

just not very attractive."

Mitchell took a similar type of risk in the dissonant vocal harmonies in

"Ethiopia" (Dog Eat Dog, Geffen), a searing portrait of environmental

devastation. "I had a girlfriend say, 'I just hate those harmonies,' and

she squeezed her face all up," Mitchell recalled. "I said, 'Why?' and she

said, 'You can't use parallel seconds.' I said, 'Well, they

said, "You can't use parallel fifths" to Beethoven. You've got these women

with dried-up milk glands and cadaverous babies with flies all over them,

migrating to God knows what end across a burning desert. You think they're

going to sing in a nice major triad?"'

On occasion, Mitchell extends the dramatic scope of a song by using guest

singers. She said, "I'll need another voice to deliver a line, because [the

songs] are like little plays. Like in 'Dancin' Clown' [Chalk Mark], Billy

Idol plays the bully. He's got the perfect bully's voice, He's threatening

this guy named Jesse [imitates his voice]: 'You're a push-button window! I

can run you up and down. Anytime I want I can make you my dancing clown!'

So you need an

aggressive, bullyish voice to deliver that line." On that same album,

Willie Nelson makes a much more low-key sort of cameo on "Cool Water," the

classic song by the Sons of the Pioneers' Bob Nolan. Nelson's voice,

Mitchell said, is "perfect for that song. That was a swing country era.

Willie is of that era, and he's got that same kind of beautiful voice. He

also sounds like an old desert rat, which is theatrically appropriate for

that song."

When you take all of these sophisticated ideas related to the vocal and

lyrical aspects of a song, and lay them on top of harmonies based on

ever-changing guitar tunings that continually pull the rug out from under

what you know and expect to hear, the possibilities of songwriting widen to

a spectacularly broad horizon. Where most songwriters aim to graft

distinctive words or a unique twist of melody onto a tried-and- true song

structure or arrangement, Mitchell takes far more risks and far more

responsibility. To extend her theatrical metaphor, she is set designer,

stage manager, star actor, and supporting cast all in one. Every part of

the production is open for reinterpretation and reinvention as Mitchell

follows her restless muse.

Copyright protected material on this website is used in accordance with 'Fair Use', for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner(s). Please read Notice and Procedure for Making Claims of Copyright Infringement.

Added to Library on January 9, 2000. (6307)

Comments:

Log in to make a comment