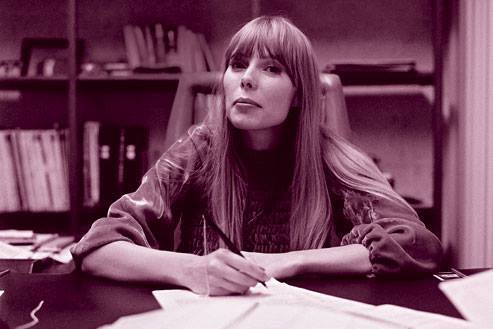

Joni Mitchell is a God among men

It was 1969 at a dairy farm in the Catskills of New York, the August sun glaring heavily down on the backs of 400,000 patrons. The small town of Bethel was overrun with young people; they were there for the Woodstock Music and Art Festival, whose organizers originally only expected 50,000 to come. Instead, the three days of the festival marked a pivotal moment in American cultural history - Woodstock became a symbol of freedom which encompassed some of the most iconic moments in music during that time. Carlos Santana climbed the stage scaffolding, the Grateful Dead performed until they blew out their amps and legends like Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix inspired generations to come. Struck by the event, Joni Mitchell wrote her masterpiece "Woodstock," which she shared with then-boyfriend Graham Nash to perform at the festival. The song became a lasting image of those three days, but also an anthem of the phenomenon that is that era's counterculture; a piece of the Aquarian age which serves as a window into the past.

The real power of the song comes with its timelessness - Mitchell's core sentiment of "getting back to the garden" is a universal desire, especially for those who work towards change. Her lyrics go beyond the tune itself, functioning as a poetic reflection on the festival's meaning within the late 1960s zeitgeist. To Mitchell, we are all "stardust," "golden," "billion year old carbon," all the same in the dream to move forward in our lives and societies. Woodstock '69 was the tipping point for this movement in music culture, an event which united thousands of young people to collectively celebrate the art of their time. This unification was made even more poignant by the looming presence of Vietnam, as anti-war efforts reached a fever pitch within counterculture and the general population alike. Mitchell even weaves the war into "Woodstock," seeing "bombers turning into butterflies" in the skies above her.

Though it seems like a blip in history from the present perspective, Woodstock was a phenomenon which meant more than just what occurred during those three days. It was an incredible collection of the era's most famous and culturally pervasive musicians, poster children for the "free love" movement, the rebirth of folk, the height of rock 'n' roll and the rise of funk. Even with this, the legacy of Woodstock '69 goes beyond its iconic music, and instead lies within the intention of the thousands who attended. The festival was a unique moment to come together in a time of political and social turmoil, an opportunity to collectively shout against the powers which held back America's inevitable evolution. It was an effort to rebuild the country's soul, or at least mark a turning point clearly within cultural history - a chance for thousands of young people to be, as Mitchell sings, a "cog in something turning."

In a time where music festivals saturate the popular sphere, it's important to remember Woodstock as a benchmark for what they can truly offer to society. Though festivals like Coachella and Lollapalooza are slowly being lost to commercialism, there is still a nugget of cultural importance in the idea that they are built on. When that many young, interested and musically savvy people gather in one place, there is always the potential for social and artistic change. Woodstock '69 held incredible meaning during its time and still does today, reminding us of the power that unity in art and culture can have in periods of chaos. As Mitchell writes, our country is too often "caught in the devil's bargain" of greed and disillusionment - it's the responsibility of counterculture to reel against this bargain through a collision of innovative art and social awareness, no matter how hard it may seem. Woodstock's status as one of, if not the most famous festival in American music history acts as evidence that unity and the celebration of art can truly shift the course of culture to pursue a different future - that festivals have the potential to help us find "the garden" of change we all seek.

Copyright protected material on this website is used in accordance with 'Fair Use', for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner(s). Please read Notice and Procedure for Making Claims of Copyright Infringement.

Added to Library on March 7, 2018. (23475)

Comments:

Log in to make a comment

DeanG on :

Interesting article. I've always thought 'Fiddle & drum' was an outlier within Joni's canon. It's her only unaccompanied song, and the only overt anti-war protest song. This article made me think about her status as a multiple outsider; as a 'girl' amongst the 'boys' and as a Canadian amongst the Americans. I wonder why she felt able to write one, but only one, protest song?