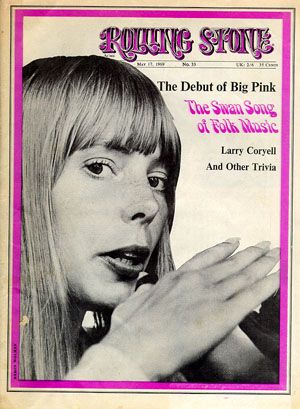

Photo by BARON WOLMAN

Folk music, which pushed rock and roll into the arena of the serious with protest lyrics and blendings of Dylan and the Byrds back in 1964, has re-entered the pop music cycle. Once again, with a new crop of guitar-toting, composer-singers at the vanguard, folk is "in."

As with country, jazz, and other rock music satellites, it is not 100 percent pure. Joan Baez is completely off of her abortive rock-album trip, but there's a solid country beat to her Dylan LP. Peter, Paul and Mary couldn't have been serious singing "I Dig Rock and Roll Music"; nevertheless they used a full complement of session men (and even backup voices) for their Late Again album. Dylan is back to the basics, leaving the electronics mostly to the boys in the Band, but his next LP--as with his John Wesley Harding--are Nashvilee-twanged.

The old names are back, but in more commercial regalia. Judy Collins, softened, orchestrated, countrified (and even, on national TV, miniskirted) is a popular chart item now, after years of limited success. The music (someone called it "Art Rock" but that can be ignored) features a lighter, more lyrical style of writing, as exemplified by Leonard Cohen. As if an aural backlash to psy-ky-delick acid rock and to the all-hell-has-broken-loose styles of Aretha Franklin and Janis Joplin, the music is gentle, sensitive, and graceful. Nowadays it's the personal and the poetic, rather than a message, that dominates.

Into this newly re-ploughed field has stepped Joni Mitchell, composer, singer, guitarist, painter and poetess from Alberta, Canada.

Miss Mitchell, a wispy 25-year-old blonde, is best known for her compositions, "Michael from Mountains" and "Both Sides Now," as recorded by Judy Collins, and "The Circle Game," cut by Tom Rush. She has a first LP out (on Reprise). A second album -- recorded during successful concerts at UC Berkeley and at Carnegie Hall--is ready for release, and another studio album has already been recorded. She is editing a book of poetry and artwork; a volume of her compositions will follow shortly. And she has received a movie offer (to conceive, script and score a film).

Not bad for a girl who had no voice training, hated to read in school, and learned guitar from a Pete Seeger instruction record.

Just who--and what--is Joni Mitchell, this girl who's so obviously perched on the verge?

For those who don't spend hours in audio labs studying the shades, tones, and nuances of the human voice, Miss Mitchell is just a singer who sounds like Joan Baez or Judy Collins. She has that fluttery but controlled kind of soprano, the kind that can slide effortlessly from the middle register to piercing highs in mid-word.

Like Baez, Miss Mitchell plays a fluid acoustic guitar, like Collins, she can switch to the piano once in a while. And her compositions reflect the influences of Cohen.

On stage, however, she is her own woman. Where Joan Baez is the embattled but still charming Joan of Arc of the non-violence crusade, and where Judy Collins is the regal, long-time lady-in-waiting of the folk-pop world, Joni Mitchell is a fresh, incredibly beautiful innocent/experienced girl/woman.

She can charm the applause out of an audience by breaking a guitar string, then apologizing by singing her next number a capella, wounded guitar at a limp parade rest. And when she talks, words stumble out of her mouth to form candid little quasi-anecdotes that are completely antithetical to her carefully constructed, contrived songs. But they knock the audience out almost every time. In Berkeley, she destroyed Dino Valente's beautiful "Get Together" by trying to turn it into a rousing sing-a-long. It was a lost cause, but the audience made a valiant try at following. For one night, for Joni Mitchell, they were glad to be sheep.

In Laurel Canyon, where she shares a newly-purchased house with Graham Nash, Joni sits on an antique sofa and bemusedly shrugs her shoulders. She is talking about an offer from a giant Hollywood film company to write a movie--"on any theme I want to choose"--for a huge amount of money. She is talking about her book of poetry: "The poems are already written. It's just an eclectic collection of all kinds of things I've done that I don't know what else to do with them. I'm putting them into a book because I don't like to lose anything." And she is showing her artwork--fine pen-and-ink drawing; felt pen watercolors; a self-portrait for her second LP cover. Some of these, too, will find their way into a Joni Mitchell book.

Whatever she's going to say next will be an understatement.

"I have so many irons in the fire now," she says.

Joni lives in a house filled with the things she loves. Antique pieces crowd tables, mantels, and shelves. There are antique handbags hung on a bathroom wall, a hand-carved hat rack at the door; there are castle-style doors and Tiffany stained glass windows; a grandfather clock and a Priestly piano. Nash is perched on an English church chair, and Joni is in the kitchen, using the only electric lights on in the house. She's making the crust for a rhubarb pie.

"Lately, life has been constantly filled with interruptions. I don't have five hours in a row to myself. I think I'm less prolific now, but I'm also more demanding of myself. I have many melodies in my mind at all times, but the words are different now. It's mainly because I rely on my own experiences for the lyrics."

The difference in experiences is the difference between the urban centers of the east--Detroit, Boston, Philadelphia, New York--and California, where she arrived late last summer.

"In New York, the street adventures are incredible. There are a thousand stories in a single block. You see the stories in people's faces. You hear the songs immediately. Here in Los Angeles, there are less characters because they're all inside automobiles. You don't see them on park benches or peeing in the gutter or any of that."

Joni Mitchell, after schooling in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, wanted to be a commercial artist. She attended the Alberta College of Art in Calgary. While studying art, she took up the ukelele.

The guitar--with the Pete Seeger record--followed shortly. "But I didn't have the patience to copy a style that was already known." Joni dumped the record and learned the guitar by experimentation, so that today she re-tunes her guitar after almost every act and she plays direct harmony to her own singing.

Her vocal training was no less informal. "I had none. I used to be a breathy little soprano. Then one day I found that I could sing low. At first I thought I had lost my voice forever. I could sing either a breathy high part or a raspy low part. Then the two came together by themselves. It was uncomfortable for a while, but I worked on it, and now I've got this voice."

But the poetry--the writing. There must have been a solid literary background; some early influences or guiding lights.

"The only time I read in school was when it was compulsory, like for a book report."

Miss Mitchell reads more now than ever before. Herman Hesse is a favorite author; Leonard Cohen her favorite poet, with Rod McKuen also on her side.

In short, Joni Mitchell seemed almost totally unprepared for her jump into the United States folk circuit in 1966. Further, "I started at a time when folk clubs were folding all over the place. It was rock and roll everywhere, except for a small underground current of clubs."

But Joni had been making the Toronto scene for more than a year by the time she hit Detroit, and she had written a number of good tunes. Tom Rush, in Detroit for a gig at the Checkmate, heard some of them, and decided to record "Urge for Going" and "The Circle Game." Joni Mitchell had broken water.

She drifted to New York where, in the fall of 1967, she met her manager, Elliot Roberts. There, too, she met Andy Wickham. He signed her to Reprise.

Now, despite the current clamor for her time, Joni Mitchell looks forward to writing songs about "peaceful things."

In concert, she does a number called "Song for America":

Why did you trade your fiddle for your drum?

We have all come to fear

the beating of your drum ...

And her first LP was produced by David Crosby, the politically-aroused ex-Byrd. "So I can't help but know what's happening. But I also know that I can't do a thing about it."

"It's good to be exposed to politics and what's going down here, but it does damage to me. Too much of it can cripple me. And if I really let myself think about it--the violence, the sickness, all of it--I think I'll flip out."

Joni Mitchell has arrived in America.

Copyright protected material on this website is used in accordance with 'Fair Use', for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner(s). Please read Notice and Procedure for Making Claims of Copyright Infringement.

Added to Library on January 9, 2000. (26584)

Comments:

Log in to make a comment