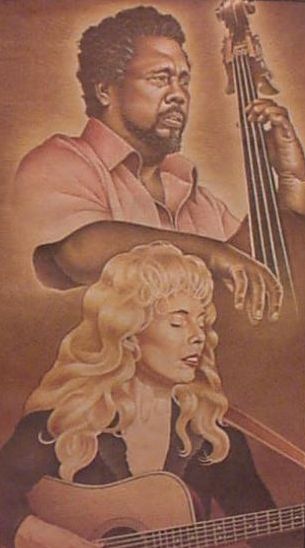

The package Joni Mitchell's MINGUS comes in is deceptively serene with its cool white and iridescent blues - misleadingly neat, as though Mitchell had the answers all wrapped up. Inside's where the loose ends are. There, the whole apparatus - one explanatory text, four paintings, five documentary fragments - may be necessary to shore up Mitchell's huge thrusts and steel ambitions. Look, the foundations haven't even been laid yet, and she's trying to build skyscrapers, playing jazz.

There's an angry percussive edge to Mitchell's guitar now, different from the drone and steady rolling rhythms that impelled HEJIRA and parts of DON JUAN'S RECKLESS DAUGHTER. There's a taste for dissonance - slackened strings, the whang of wire against metal fret - and one ice-cold, sweetly reasonable vision of raw evil. Sometimes it seems as if the tensions Mitchell's courting start to drive her crazy. Phrases end in thuds and sharp noises - a fist slamming down hard - as though she thinks there's a chance that whatever resists reason or an artist's license might succumb to brute force. There are times, too, of consolation and even ecstasy - not many, maybe not enough. But then, what we've got here is a requiem for unbelievers.

You will have heard by now that MINGUS began as a joint venture between the headstrong singer songwriter and the master jazz composer. And that the collaboration (his idea) turned, with a snick of fate's switchblade, commemorative when Mingus died in Mexico of a long-haunting disease. Charles Mingus left Joni Mitchell engulfed and wrestling with his influence, and with a handful of his tunes she'd set to words. Even though the songs (including two all her own) have now been laid down in tributary arrangements - and the Mingus raps so carefully placed they seem stiff as a funeral suit - there's still more sense of struggle than piety on the album.

Like the beasts she's occasionally chosen as her emblem, Mitchell seems some sort of scavenger - a coyote or a crazy black crow, all beak and bravado. She's got some be-bop mannerisma: hear how she wiggles a final note, "*eeuh-eeuh-ee.*" And the woman takes *liberties* - goes singing Mingus' past, his illness even, in her own first person. But then, coworking can't come easy to someone unconcerned with popular idioms and almost proudly ignorant of theory. Joni Mitchell says she worships genius, distrusts craft and bets it all on inspiration. No wonder she flutters and squawks. Bending her work to his is both a threat and a nervy liberation.

For one thing, Mingus' melodies give Mitchell's lyrics different-shaped spaces to fill. Analysis, which she tries in "Sweet Sucker Dance," falls flat. It's out of step with his allusive conversational cadences, at odds with the music's equivical moods. She chooses narrative in "The Dry Cleaner from Des Moines" and is left huffing and quavering behind the jumpy beat. The song only begins to move when she throws out the story and just croons with the horns a little. In "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat" (Mingus' tribute to Lester Young), her lyrics are resonant and righteous, a burst of compressed elegance:

When Charlie speaks of Lester

You know someone great has gone

The sweetest singing music man

Had a Porkie Pig hat on

Who in this bareheaded generation knows what a porkpie hat looked like, anyway? When Mitchell speaks of Young, you *see* him. And as for Mingus, you feel his presence here more than anywhere on the record. I think Joni Mitchell imagined him as both a shaman and a bogyman (her paintings suggest this), and from time to time, found herself face to face with a suffering eminence in a wheelchair. It must have been a tricky relationship: part teacher-student, part colleague-colleague, a bit of age versus youth, a touch of man-woman. "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat" puts all these images together. Charles Mingus, after all, wrote the piece for an older teacher-colleague, and Mitchell bats his own words back at him and retells his stories with the right mixture of awe and sly affection.

Requiems are supposed to close with affirmations and visions of the afterlife. MINGUS does. At the end of "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat" (the last song), Mitchell, like some Manhattan Dante, is led up from the subways through clouds of steam to the bright but not-exactly-celestial city. She finds it so saturated with the music of generations of jazzmen that even the taxis blow in tune. As she says at the album's beginning, "God must be a boogie man." Of course, whenever she sings that line, the kind of raucous chorus Mingus himself used sings it back, roughing up her own cool, swooping melody, poking at her crystal-blue theology.

It's a tug of war - like the ones Mitchell's always getting caught up with in her songs - between the myth or the romance or the dream and the lowdown, dirty real. She could almost be making fun of herself. On the other hand, so much of MINGUS is at odds. I don't just mean the battle of wills inevitable in such a collaboration, or even the evident constraint between singer and players that turns what should be a wake into a tumbling, graveside consolation. There's so much restlessness here. Mitchell's harmonies veer away from resolutions. Her tunes twist and knot as if they, too, became impatient with the smooth logic of her sentences, the constant and confident analysis. It used to be lovers who let her down. Now it's reason, God, the devil, art. How many pretty words and melodies make up for the petty indignities of decay, the banality of evil?

For all its benedictions and affirmations, MINGUS' strongest moment is its grimmest. "The Wolf That Lives in Lindsey" is Joni Mitchell's "Dies Irae," but where traditional requiems look to some far-off final judgment, Mitchell's apocalypse is now. In Hollywood, a killer haunts the hillsides, wolves howl around the patios, and blizzards sweep through prefab bungalows. The world's tilted, and if Lindsey "loved the ways of darkness beyond belief," he's not the only one. Mitchell's belief has been stripped here to a couple of bones: there are laws of nature no one can beat. But she doesn't sound sure. Snow comes and goes where no snow's supposed to be, and almost every line of her melody ends on an odd rising interval. The notes fling her voice up like a grappling hook.

That's it - clawing at walls, challenging the implacable. Joni Mitchell keeps asking the hard questions, touching nerves. And the pressure she applies is increasingly brutal, increasingly deft. It's been a long time since her songs had much to do with whatever's current in popular music. (She would prefer we call them art songs.) But then, she doesn't so much come on as an outsider, but as a habitual non-expert. She's the babe in bopperland, the novice at the slot machines, the tourist, the hitcher. She's someone who has to ask. Which doesn't mean she follows orders or even listens to directions. But when you're lost in the mystery and the maps don't mean a thing, it's nice to be with someone who rolls down the windows and hollers.

Copyright protected material on this website is used in accordance with 'Fair Use', for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner(s). Please read Notice and Procedure for Making Claims of Copyright Infringement.

Added to Library on January 9, 2000. (13122)

Comments:

Log in to make a comment