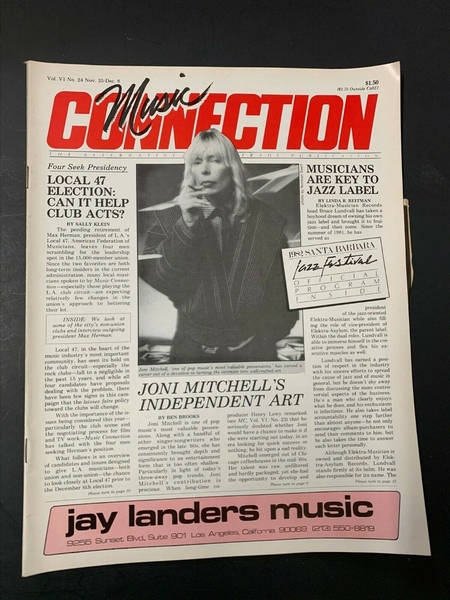

Joni Mitchell is one of pop music's most valuable possessions. Along with a handful of other singer/songwriters who emerged in the late '60s, she has consistently brought depth and significance to an entertainment form that is too often shallow. Particularly in light of today's throw-away pop trends, Joni Mitchell's contribution is precious. When long-time co-producer Henry Lewy remarked (see MC, Vol. VI. No. 23) that he seriously doubted whether Joni would have a chance to make it if she were starting out today, in an era looking for quick success or nothing, he hit upon a sad reality.

Mitchell emerged out of Chicago coffeehouses in the mid-'60s. Her talent was raw, unfiltered and hardly packaged, yet she had the opportunity to develop and grow without compromise, and today she still projects much of that individuality and rawness when she writes and particularly when she records.

In the interview that follows, Joni, as articulate in talking about her music as she is in making it, offers a number of insights into her personal philosophies. For her, and for Henry Lewy, who also takes part in the interview, the recording process is an obvious extension of personality and philosophy.

MUSIC CONNECTION: How come you two have worked so long together?

JONI MITCHELL: I like Henry...(laughing)

MC: Most artists work with producers for three or four albums at the most, then...

HENRY LEWY: I'm not a producer...

MITCHELL: There is no producer on my albums - that's why it works. With no producer there's less animosity. I think that's one of our secrets.

On my second record I got so made at a producer because he killed my spirit. He finally got a very good performance out of me but it was painful. I would be doing a take, sailing along, and all of the sudden, bang, the Voice of God would come over the microphone saying, "you're off your mark or you're swaying to the right of the microphone, etc."

There's a spell you have to go into to perform and if you get broken into a few times, you lose it. Studio musicians learn to deal with that kind of squashing with time, but I think it callouses them eventually.

MC: Henry doesn't use the talkback?

LEWY: No, we use signals. We've got a real good system worked out by now that's proven.

MC: Really? What is it?

LEWY: To just let Joan do what she wants to do. (laughing) Basically that's what it is.

MITCHELL: Which is fantastic! And I let my players do what they want to do unless I see them looking at me like, "What am I supposed to do?"

Then I have to take control a little bit. The same thing happens if I don't know what I'm doing in pockets. I turn to Henry in the control booth. We have a support system where we get that feedback. But it's more like a free-school method. I'm kind of an anti-academic to begin with. But there must be authority...

MC: Right, that's what I'm getting at.

MITCHELL: Well the way I look at it, I'm not the authority. I'm probably the one that worries the most about it. The authority is really the basic structure itself. Either an idea or concept complements that basic structure of it messes it up. Since I'm working with studio musicians, the main thing that I try to get is for them to go past the level they go to with most producers, which is, come in, identify the bag and give the producer the stock thing out of the bag.

For me it's to get them to forget about that for the most part. We're looking for something else that only comes when the climate is right.

You can't always get that, but that's what we try for.

"I hate to say there's no ego involved-there has to be for the creative process. But ego is very fragile. If you squash it or thwart it, you don't get good music. There's room for people to get frustrated. The way I see the producer-and remember, I'm kind of an anti-authoritarian type-is as a spirit-squasher. I know there are good producers, in all fairness, and that they're necessary in some arenas, but so many times I've seen them become like a director on a movie set...who's another kind of spirit squasher. The artist's opinion is diminished and there's an act of condescension between director and artist, and that act is an insult to the intelligence of the artist. Once it's perceived, there's no climate for artists to surpass themselves.

There's nothing more thrilling for me than to see people with their eyes glazed over listening to something that they didn't even know they played. In other words, to bypass intellect-to go into the area of intuition to a greater degree. That's where jazz comes from. Jazz is an opportunity to go out and bring back the goodies...to sail past intellect. And a producer is the antithesis of that. He is Mr.

Awareness-every note is a known. Some of the most beautiful things are unknowns, even to the person who's playing their axe. As soon as you start thinking too much, everything stiffens up. The ideas lock in.

MC: I'm told that this new record has taken longer to make than any other in your career. Henry says you've re-cut most of the songs several times.

MITCHELL: yes, we have. But each time we've re-cut with this album we've left some of the invention from the earlier take. Then the next team would come in and we'd take the best from that group of musicians. So the whole thing has been like painting preliminary sketches.

MC: Have you grown up in the studio after all these years of recording? Do you feel in control?

MITCHELL: I'm still an infant in here. I learn something every year. The state-of-the-art keeps changing. My ear for sounds is much more acute now. I'm more aware of what's happening to things through the board. Now there's a lot of gadgetry-you can use it subtly or flamboyantly and you have to develop opinions on how you want to use it. So that's a whole new thing to learn.

MC: I remember thinking that Court And Spark was as sophisticated as anything I had ever heard. It had such a state-of-the-art sound.

LEWY: Well, it was also fairly simple because we were dealing with an organized band that was a unit.

MITCHELL: I'm very protective of my structure. My music-because of the open tunings and everything-moves around and also has odd rhythmic punctuations. If you lock into them too much it gets kind of classical. It's a very tricky business to laminate a band onto my chunk-a-chunk-a, which has strange voicings. That band was really good at doing it because they mostly stuck to lines that were moving in the guitar part already. The horn lines were just doubling bass lines that were happening in the guitar. I was very protective that they wouldn't just scribble all over the architecture of my music.

LEWY: Most of the stuff that you hear on Joan's new album still comes from her guitar. That's why we've been cutting basic tracks with very few people. We've been doing basics with bass and drums, so that everybody hears and doesn't over-ride. With too many people it was just the guitar strumming along in time giving away to everybody else.

MC: Then the guitar just becomes a rhythm instrument. This new album sounds very pop and much more accessible than the last few albums. Can you explain the evolution?

MITCHELL: When we came to this album I was in kind of a quandry. I thought I might go all the way back to the roots. It spun out so far with the last jazz album. At that time I was so sick of the downbeat between disco and rock 'n' roll. All the rhythm was becoming cliche to me. So when I did the jazz album, I had everybody playing free. The drummer wasn't even keeping the beat-everybody was playing flurries. It was abstract expressionism.

So when I got that out of my system, I got a craving for the groove and simultaneously I thought, "I don't want the hassle...I just want to make a nice little folk album.' But somehow or another-I don't know what the process was-we ended up doing this thing.

LEWY: We used some of the songs from a few years ago and they've completely changed into a groove that seems very timely. People hear it and say, "Oh, there's nothing like it on the air right now, but it's very commercial" And, Joan can dance to it, which is one of the basic criteria.

MITCHELL: These players that I'm working with are a new breed of musicians in my experience. They play rock 'n' roll well and jazz well.

MC: Who's on the album?

MITCHELL: Wayne Shorter, Steve Lukather, Larry Carlton, Michael Landau, John Guerin, Larry Williams and some other great players.

MC: I imagine you have pet peeves about each other after working so long and close together.

MITCHELL: It gets tense. Sometimes I work real hard. The hardest thing for me is to click gears. There's a mood I get in that's really difficult. You come in on one side of the glass and you've got to be the scrutinizer, the critic. You go out there and you have to put away your critic in order to free up and get the spirit up. Sometimes changing those gears gets actually impossible. That makes for a kind of growly night, and everybody can feel it. Everybody has those days.

Maybe Henry has a bad day or something like that. Spirit is real important and you can't help being in a bad mood sometimes. We've been locked in here for a year! It's delicate because everybody is affected by your mood.

LEWY: The main thing is that there's plenty of room for everybody. Nobody's going to say, "You can't do that." We say, "Let's try it," because I know Joan's got enough intelligence to realize that after listening to something three or four times it either works or it doesn't. A lot of times I've said, "Well it's impossible," and she's proved me wrong. Those times have been beautiful strokes of genius.

MC: It sounds like you have a style of working where spontaneity and expediency are essential. How do you accomplish those things when the nature of recording often requires long hours of getting sounds and levels, etc.?

LEWY: We don't spend an hour getting drum sounds. I used to spend five minutes. Now we spend a little more. When the musicians and artists come in the studio, I don't want to waste any time and lose their enthusiasm. I don't want some drummer to sit there going bang, bang, bang for a half an hour while everybody sits around, so within ten minutes we're going and the tape is rolling. We record every rehearsal and everything.

MITCHELL: Ooh, and the jams sometimes...

LEWY: Sometimes we get fantastic jams because three musicians get together for the first time. Our basic track sessions go very fast.

Where we take time is when Joan goes and does vocals and harmonies and guitars. She's a severe critic of herself.

MC: Joni, do you always do a whole vocal performance each time you make a pass at a tune?

MITCHELL: Yes, we've got a system. I usually do five takes or so and do a composite from the fiver performances. Any one of those performances is a good one, but listening to it over and over, the weak spots become increasingly apparent. A live performance is obviously a different art. It goes up into the air.

So we have a system that doesn't lose spirit. We do several takes and when I feel like I don't have any more in me I quit and we make a combine of that. One take is usually the best and we take bits and pieces of the others.

LEWY: In the early albums when Joan was just doing piano or guitar and vocal, we used to do three or four things and cut them together. So it was still performance cut to performance.

MITCHELL: And the very early things were just pure takes-there was nothing done to them. I couldn't overdub then...This career has been like college for me. At that time, I was literally just a folk artist-a primitive. You just sat me down in front of a mic and waited until something nice came out.

Mitchell's new album was released in early November to wildly favorable reviews and a good deal of airplay. The LP is already being hailed as her return to accessibility.

Copyright protected material on this website is used in accordance with 'Fair Use', for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner(s). Please read Notice and Procedure for Making Claims of Copyright Infringement.

Added to Library on March 25, 2009. (1496)

Comments:

Log in to make a comment