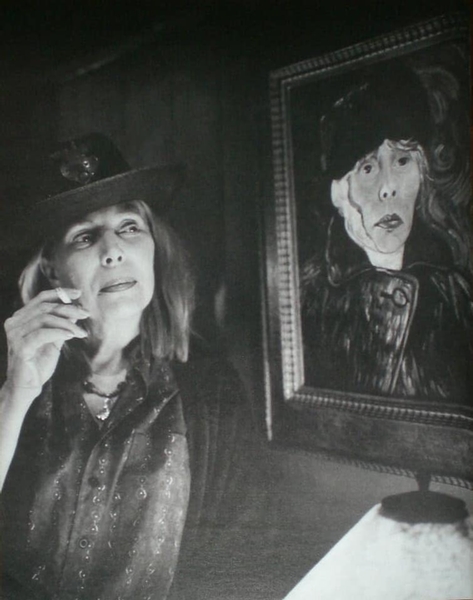

"We are stardust we are golden," Joni Mitchell sang an age ago in "Woodstock," paving the way for a generation of artists to open their imaginations to the gleaming potential of pop and to making music that matters. Here, Mitchell and Camille Paglia discuss how striving for those ideals, in these new, uncertain times, has never seemed more crucial

In her new best-selling book, Break, Blow Burn: Camille Paglia Reads Forty-three of the World's Best Poems (Pantheon), Interview's contributing editor Camille Paglia offers a meditation on Joni Mitchell's classic song "Woodstock." Here she talks with the music legend about her new album, Songs of a Prairie Girl (Rhino Records), and the many sources of her inspiration.

CAMILLE PAGLIA: Is this Joni?

JONI MITCHELL: This is Joni.

CP: Oh, wow, I'm floored to be speaking to one of the great artists of our time!

JM: So, what should we talk about?

CP: I'm interested in your creative process. You've lived a whole life as an artist in ways that are very inspiring to young people who lack role models today. As a lifelong fan of pop culture, I'm worried about the way it's supplanting artistic experience for young people now.

JM: Well, America has always loved its criminals, but in the last two decades the sediment has truly risen to the top. To me, underbelly cultures are always interesting, but when those subcultures grab the reins and rise to a dominating position, especially in youth-oriented mediums, there are sociological consequences.

CP: Your music often explores the metaphysics of love-the ecstasy and melancholy, the ups and downs. Just a few days ago, I was standing in the plumbing section of Home Depot when your song "Help Me" came over the loudspeaker. It’s absolutely gorgeous and has enduring popular appeal. It captures the subtleties and emotional modalities of being in love or out of love. But that kind of complex insight seems gone. Young musicians were once the cutting edge of culture, but no more.

JM: When we started out, it was uncharted waters. I mean, it's not like I grew up playing air guitar in front of my bedroom mirror. Artists were still disreputable. I was a painter and wanted to go to art school, but my parents didn't want me to-to be an artist wasn't respectable. Then the Beatles hit, and suddenly people thought, "There's gold in 'dem hills." I never thought I'd have a record deal. I come from a wheat-farming community where it's the tall poppy formula: Stick your head above the crown, and they'll be happy to lop it off for you! [Paglia laughs] You weren't encouraged to be exceptional unless it was about getting A's in school-but there's no creativity to that.

CP: That is why your body of work has such quality. You were developing your imagination and your voice before outside commercial pressures began. Now young people instantly covet the recording contract. Unfortunately, the fabulous music-video revolution of the '80s degenerated and turned music into image and posing.

JM: I heard a record executive say on the radio that they were no longer looking for talent but rather for a look and a willingness to cooperate, because with Pro Tools they can fix anything. There's always been a disposable quality to this business.

CP: I've been teaching at art schools for most of my career, and I can clearly see the way the business is short-circuiting young artists' development. They don't have time to percolate.

JM: The reason I did is because the record company didn't value me at all. This was to my advantage. They got me dirt cheap-they didn't know how to market me. I looked like a folk musician because I'd been playing in clubs for several years, which I really enjoyed. You could jump down off that stage, and you were still one of the people-they didn't gasp at the mention of your name. It was comfortable, and you could experiment. Warner Reprise had no money invested in me and therefore left me alone-not out of kindness but out of disinterest.

CP: But wasn't there a tremendous buzz in the music community about your songs?

JM: Actually, other artists would cross the street when I walked by! Initially, I thought that was due to elitism, but I later found out they were intimidated by me. Led Zeppelin was very courageous and outspoken about liking my music, but others wouldn't admit it. My market was women, and for many years the bulk of my audience was black, but straight white males had a problem with my music. They would come up to me and say, "My girlfriend really likes your music," as if they were the wrong demographic.

CP: the musical landscape has changed profoundly. In my commentary on your song "Woodstock," I stress the enormous difference between Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young's upbeat hard-rock version and the way you perform it as a moody art song. Their style had the cultural momentum for decades, but I think the hard-rock moment in popular music is over. I'm sad because it was such a huge part of my youth.

JM: I've seen things written about "Woodstock" in university courses on the '60s-they really like to nail me for the naive idealism of t, whereas you were able to get the ironic tone. At that time, I felt so desperately that we were placed here to be the custodians of the planet Eden. So for the first 10 or 20 performances of that song, I used to get a lump in my throat. I felt that the primitives who remained on the planet were still living in harmony with nature, versus us-the supreme white guy, with our scientific monstrosities, playing with half a deck! We need to get a grip on our original destiny and learn to love the wild and save what's left of it and not go paving over farmlands that we may need someday. This is the farmer in me speaking. I'm the first generation of my genealogy off the farm, so it's in my blood to think in terms of good soil and weather [laughs].

CP: This brings us to your new album, Songs of a Prairie Girl. You come from Central and Western Canada, a great open landscape that has clearly given you vision and perspective.

JM: In looking at the album I found that it's all about winter and wanting to get out of there! [both laugh] The song "Big Yellow Taxi" was inspired by my first trip to Hawaii. I woke up after my first night there, looked out the window, and saw these green mountains and white flying birds and then, down of the ground, a parking lot as far as I could see. When that song was released as a single, it was a hit only in Hawaii at first-it took people in other places a while to realize that their region was paradise and that they were losing it too.

CP: You have such a strong eye for detail, be it for nature of the city or people or colors. It's one of the hallmarks of your writing. Is it because you grew up on the prairie?

JM: Well, I'm a painter, so I tend to think in pictures and store pictorial information, like an autistic person.

CP: You're a superb model for young, aspiring artists because of your vast range: music, literature, and art all melded together.

JM: I'm a Renaissance person in that I express myself in three arts. I work to get them all up to a certain standard through discipline and observation. You have to be self-adjudicating and self-critical.

CP: You also have a gift for improvisation.

JM: Improvisation takes nerve. It requires taking a chance and also failing. You have to overcome fear. My mother was always saying, "You're too sensitive," and "You think too much for a female." That comes under the banner of that generation's "Don't worry your pretty little head about it!" In Plato's utopia, you could not be a poet and a painter and a musician. You had to pick one.

CP: Plato felt that poets and artists couldn't be trusted because they questioned authority and religion and therefore were dissidents who would threaten the stability of the ideal state.

JM: Absolutely. I did an album called Dog Eat Dog [1985], which was not well received. It contained headline stories, such as the fall of Jimmy Swaggart.

CP: I know you take the issue of evangelical Christianity very seriously.

JM: I take the marriage of church and sate very seriously. On Sunset Boulevard during the Reagan era, there were pink billboards with black letters saying, "Rock 'n' Roll is the Devil," signed by Jerry Falwell and the Moral Majority. Reagan was very cozy with him. When I put that album out, the church was watching rock 'n' roll, playing it backwards, looking for diabolical messages. When the album was released, I was challenged to a debate on THE 700 CLUB by Pat Robertson, though I got congratulatory letters from an Episcopalian Church and from the Crystal Cathedral, which really surprised me. They said, "We need more artists like you."

CP: During the George W. Bush administration, the evangelical movement has intensified its cultural pressure in the U.S. There are more and more cable TV channels devoted to religious broadcasting.

JM: Oh, it's very lucrative. It's a nice little business to get into if you're a good rapper.

CP: The big scandals involving Jimmy Swaggart and Jim Baker made evangelists seem to disappear for a while, but they were still powerful under the national media radar. You took a strong public stand against them.

JM: Swaggart was declaring war from the pulpit [paraphrasing her song "Tax Free" from Dog Eat Dog]: "Our nation has lost its guts, our nation has whimpered and cried and pandered to the Khomeinis and the Qaddafis for so long that we don't know how to act like men." He even declared war on Cuba! I watched all the televised church services in search of an honest man, and all I saw were criminal con men fleecing the flocks. Christianity is an ancient Egyptian myth, laminated, presented like the history of a person who actually lived. Most of the story is ancient mythology-walking on water, virgin birth. Don't get me started on the scam of Christianity!

CP: Early Christianity was about renouncing materialism and worldly status. That's what's troubling about so many TV evangelists soliciting cash.

JM: Christianity was basically the Roman Empire in disguise.

CP: What part did religion play in your youth?

JM: My father was Lutheran, and my mother was Presbyterian. So they went to the United church, which was for mixed Christian marriages. I broke with the Church at age 7, because Genesis raised a lot of questions for me-it seemed like pages had been ripped out of the book. I'd ask in Sunday school, like, "Why did God punish Eve when he was really after Adam?" That story has been compelling to me all of my life.

CP: So your parents were religious?

JM: No, but they went to church. That's a distinction. My grandmother was a Bible beater-she quoted the Bible, and my mother quoted Shakespeare, mostly Ophelia's father, Polonius, all that platitudinous stuff.

CP: So how did you manage to break with the church mentally at 7, given that the community was so conformist?

JM: The church was loaded with holy hypocrites. Basically, it was a place to wear your new hat. But there came a new preacher, one of the great heroes of my life, a Scottish minister with a Burmese wife who never converted from Buddhism. He gave the only inspired sermon I ever heard. My father and I still talk about it.

CP: How did your interest in the visual arts begin?

JM: With Bambi [1942]. I always drew, but, being a sensitive child, he fire in that film haunted me. The downside of sensitivity is that when you get stuck on a topic, you can't get off it-it's another quality that artistic and autistic people share. I was down on my knees for about three days after that movie, drawing forest fires and deer running.

CP: You have a fire image on the front of Dreamland [2004].

JM: Oh, that's just George W. Bush burning down the world. All my paintings lately have been Bush bonfires. It's the same as the forest fire in Bambi, with the hideous white hunger. CP: So that film started your drawing and painting?

JM: That, and something that happened in the second grade. There were so many of us that year that they annexed a parish hall and dragged an old lady out of retirement to teach us. She put all the A averages in one row she called the Bluebirds, all the B's in a row called the Robbins, the C's in a row called the Wrens, and the D's. I was in the C row. I remember how the A's looked so smug and pleased with themselves, but I didn't like any of the kids in the A row. I liked them better in the C and the D rows-the ones who were bored and not trying or even the ones who were a little simple. I have this prejudice against the illusory sense of attainment associated with the educational system on this continent.

CP: I totally agree!

JM: Yes. I see that in you. I'm glad you exist and have a good loud voice, because you can do some good in terms of reeducating about poetry and everything. Thank you for including me in your book, which took some nerve.

CP: I love that my book starts with Shakespeare and ends with Joni Mitchell! I write that in the 40 years since Sylvia Plath's "Daddy," no poem written in English has been more important, influential, and popular that "Woodstock."

JM: The irony is that the line "I dreamed I saw the bombers riding shotgun in the sky/and they were turning into butterflies above our nation" has been taken as girly and silly and too idealistic. But the point of it is, we've got to do that-if we don't we're done. There's a genuine urgency. Huge numbers of species have become extinct, and when that many species go, everything is out of whack. Now everybody's got these damn bombs, and they're testing them underground and under the ocean.

CP: At what point did you become an environmentalist?

JM: I grew up in a really tough town-the kids were as mean as New York kids, so when they got too much for me, I would ride my bike out into the country. I'd sit in the bushes, smoke, and watch the birds fly. I wrote a poem when I was 11 about a boy living on a ram who overhears his father saying he's going take this bluff down, and the bluff is everything to the boy. I take it through all of the seasons: "Slapping a puck into an orange crate goal, applauded only by the wind that banged and clanged and shuttered in the greenery door."

CP: So you could have been a poet, yet you began to work with the piano.

JM: Why am I not a poet?

CP: No, you are a poet! What I mean is that you moved from the page to music, and somehow music allowed you to express yourself more. What was the first instrument you worked with?

JM: My experience in that second-grade classroom, where I was made a third-class citizen, kind of answers that question. That teacher's approach to learning was to say something, for us to memorize it, and then to have us spit it back, which didn't interest me. I remember thinking, if she gives us something to solve that she doesn't know the answer to, then I'm in-but if not, then I don't care. What gave me the courage to become an artist though, was that one day she had us draw a three-dimensional doghouse, and everybody's was wither too tall and skinny or the perspective was off. I drew the best one, and I drew security from that. At that moment I forged my identity as a visual artist. I also pissed off the educational system by spacing out, squeaking by, and finally flunking chemistry and math in grade 12 and having to repeat it.

CP: When did music enter the mix?

JM: I had a hard time finding kids to play with, but I did make friends with two kids: One was a piano prodigy, and the other was studying opera. That was the only creativity in the community. They were considered kind of nerds, but they had imagination, and we used to put on circuses and get all the other kids involved and charge admission, which we'd give to the Red Cross. The father of one of these kids was the school principal, and sometimes he'd let us out to go to a movie. One we saw was The Story of Three Loves [1953] with Kirk Douglas, which was made up of three stories, with the piece "Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini" by Rachmaninov. The music made me swoon. I asked to buy it, but it wasn't in the budget. So I'd go down to the department store that was across from my dad's little market, and I would take the record out of its brown sleeve and go into a listening booth and play it. One day I said to my parents that I wanted to take piano lessons, and they sent me to a woman who, as all piano teachers did in those days, rapped my knuckles with a ruler.

CP: [laughs] They were horrible!

JM: Oof! Some people can survive it, but I couldn't. She killed my love for the piano. It was like the church and school, so I quit. And as a result my mother viewed me as a quitter and the expenditure on the piano as a waste of money, so years later when I wanted to play guitar, she refused to buy me one. Once I got into the music business, the next killer of my love would have been working with a producer. In the music business you have these unmusical people who are unjust and red queenish and domineering and untalented-they take a lot of your money and push you towards commerce instead of art.

CP: Is that why you didn't want a producer for much of your career?

JM: Yes. David Crosby produced my first record, but he liked my music the way it was. The record company expected him to turn me into a folk rocker, which was bankable, but he only pretended to. Then on the second record I got this really cocksure guy who was producing for the Doors. We cut one song together, and it was hell. I'd be singing with my eyes closed, and he'd burst into the middle of the performance like a heckler. Or you'd get all full of adrenaline, and he'd go, "No!" And then at the end of the session, he'd look at his watch and say, "Well, I gotta go produce the Doors, but I'll be back in two weeks." So I asked the engineer whether he thought we could get the record done before he got back, because if I had to work with him, my love of music was going to die. He grinned at me and said he thought so, and we got the record done within those two weeks. I never used a producer again until I married Larry Klein.

CP: So you were producing yourself?

JM: My point is, if you have a vision and you know what you want, you must definitely don't need a producer, but that was unheard of. I ultimately had to put it in my contract that I didn't have to use one. I mean, did Beethoven have a producer? Did Mozart? On Court and Spark [1974], I sang all of the melodies onto the tape. Same thing with For the Roses [1972], where some of it was written out by a scribe and reproduced by other instruments. So that was the way I was able to score my own music, by sketching it with my voice.

CP: Do ideas for songs or melodies come to you at odd times, or do you consciously sit down to try to write?

JM: Well, I don't write at all anymore. I quit everything in '97 when my daughter [whom Mitchell gave up for adoption in infancy in 1965-Ed.] came back. Music was something I did to deal with the tremendous disturbance of losing her. It began when she disappeared and ended when she returned. I was probably deeply disturbed emotionally for those 33 years that I had no child to raise, though I put on a brave face. Instead, I mothered the world and looked at the world in which my child was roaming from the point of view of a sociologist. And everything I worried about then has turned out to be true.

CP: It sometimes sounds as if you were thinking through the piano during that period.

JM: I'd just sit at the piano and lay hands on it and make shapes, kind of like abstract expressionism. But i have a gift for melody, so I know when it sounds noodley-which is more than most contemporary composers know. [both laughs] Forgive my arrogance, but it's true!

CP: I read somewhere that you particularly like Cezanne. Is that true?

JM: No. In fact in the '80s I bit the bullet and found an original voice as an abstractionist. Initially, I had no respect for abstraction, and I took that with me to art school, where all the profs were pouring paint down incline planes. [laughs] There I was an honor student because I had chops, but the attitude was: You're a commercial artist, not a fine artist, because the time of the camera has come. but for a painter especially, originality is the goal. You want to plant the flag where no one else has been, whereas in music, if you adhere to a tradition, you'll do better. If you're after money, don't try anything original in music, because you won't get the votes. In order to have a hit, you have to dumb down a lot.

CP: Do you mostly paint in a home studio?

JM: I've had official studios, especially for the abstract expressionist work, which is messy and big. But in the '90s, I thought, No, I'm going to go back to where my heart is: I'm going to paint as they did during the period of Van Gogh and Gauguin-post-impressionism. So I paint like that, although those artists were formed by their religions. You have to be trained to believe in your imagination in order to swallow the Bible, where as the Calvinists concluded that the Bible was really just an archaic relic and that Jesus would be more approving of taking long walks in the woods than he would of studying religious dogma.

CP: Calvinism has been the source of a lot of the hostility or indifference toward the arts in the U.S. The Puritan tradition was directed toward practicality and work, and therefore art and beauty were considered frivolous.

JM: Practical-I have those values, and Van Gogh had them too.

CP: Do you do your landscapes in the studio, or do you actually go out into nature?

JM: Both. But like Picasso, I never know when they're done. I live with them. I'll go, "That part is not quite right." You know, they once stopped an old man in the Louvre trying to deface a Picasso, and it turned out to be Picasso himself [laughs]. He was continuously dissatisfied and sometimes buried the best painting underneath the final work.

Copyright protected material on this website is used in accordance with 'Fair Use', for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner(s). Please read Notice and Procedure for Making Claims of Copyright Infringement.

Added to Library on July 23, 2005. (10210)

Comments:

Log in to make a comment