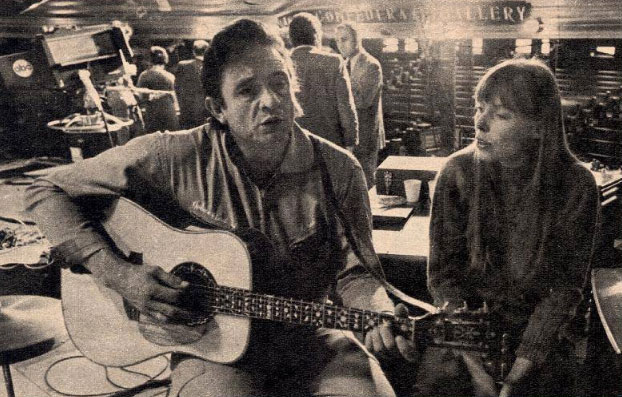

Country music chieftain Johnny Cash and poet-composer-singer Joni Mitchell harmonize during rehearsal

To watch Bob Dylan in action, I would have gone to the ends of the earth. Instead, I went to Nashville.

Making the scene in this conservative city where fellas still get their hair cut regularly is an invading army from the sky. Long-haired and bell-bottomed musicians drop down by jet in droves. Like pop pilgrims to Mecca, they are bound for Nashville's recording studios.

All this activity is the result of the nation's new fervor for foot-tapping, country-western tunes. And what better place is there for performers to deliver their various versions of grass-roots sounds than the locale where it's always been "in"? Nashville musicians were born with guitars in their hands.

Most spectacular of the recent arrivals is Bob Dylan. Nashville Skyline, his current album, came out of the Nashville studios. But even more attention-getting was his TV appearance. Ignoring all the network bids that have piled up in his years of seclusion, Bob Dylan showed up to give his friend Johnny Cash's TV show a proper sendoff.

Just what this much-publicized friendship between Dylan and Cash consists of is hard to say. Cash's wife, singer June Carter, says the two men spend a good part of their time together in silence. Cash himself gives the impression that too much has been made of it. "We're just friends. I got lots of friends" he says in his low, slow, comfortable way. Although it is a popular belief, Cash denies that the relationship began when he gave Dylan a guitar at a Newport festival five years ago. "I had brought a couple of guitars with me, and he liked one hand-made in Chicago in the early '30s. So I gave him that old guitar of mine. I've given away a lot of guitars. We first met at Columbia Records. We just became friends like any two songwriters might, you know? Mutual admiration for the other's work, I think. I was a guest of his in Woodstock four or five years ago. I saw him in England a couple of years back. Then in Nashville about a year ago when he came to record ... ''

With a promise that we could photograph Dylan along with Cash, and with a half-promise that I would be able to ask Dylan himself for an interview, photographer Dan Wynn and I had come to record the rare event. Here is what we found:

Scene I

The stage of the Grand Ole Opry House, enlarged by a temporary extension for the Johnny Cash show.

THE CAST: Johnny Cash, his wife June, executive producer Bill Carruthers, singer Joni Mitchell, singer-fiddler Doug Kershaw, public relations man Jeff Rose, photographer Wynn, me, various walk-ons.

The scene opens with Carruthers explaining the situation. It is 9:30 a.m. Dylan is not expected until 5 p.m.

CARRUTHERS: Bob looks up to John, as you know. To be very frank with you, he wouldn't do this unless John had asked him to. I can't tell you how uptight he is. We've had maximum security problems. The set went yesterday, and it was this, that, and the other thing. It's a very pathetic study of a guy. Bob feels that any artificiality would make his fans think he was trying to become something he isn't, so he wants a bare stage, and that's exactly what we're doing. We prefer not to, but I promised Bob to do everything for him that we could.

ME: How does Cash feel about changing the set?

CARRUTHERS: John had given his word as I had mine ... Yesterday there was an incident on stage here. Even though we did have maximum security, some kid got through and forced himself on Bob, and there was a scene where the police had to throw the kid out of the theater.

And Bob felt badly about it. Bob didn't feel put upon. He was the center of attraction, and he hates it-just hates it. And I can only tell you that the string is very taut at the moment regarding Bob Dylan even doing the show. I'm only saying he's on the edge. But he's sticking it out because of Johnny. Now he said to me yesterday, "Please, no photographers because I look bad." Well, he doesn't look bad. Bob looks better today than he ever has. He's been out fishing with Johnny and looks healthy and suntanned and wants to wear a suit and a tie on the show. He's got a little bit of fear. This whole thing ... He's trying to change. And, you know, he's such a deep little guy that you can tell the moment he's upset because there's a little twitch in his eye or lip. So I've given my word to everybody that there will be no photographers on stage. (June Cash, pretty enough to be the reason all those men rhyme her first name with moon, comes by.) This is Carol Botwin and Dan Wynn. They've come down from This Week Magazine, and they want to shoot a cover. I've explained how Bob feels about photographers.

JUNE: Can't they take pictures from the balcony? We can't control it, up there. We don't want. to upset Bob. We're just glad he's here.

ROSE: At this point we'll just have to wait and see ...

CARRUTHERS: I had to throw Look magazine off the stage yesterday. He just got uptight.

JUNE: When cameras get up real close to him, he just gets up in knots. Everybody knows this.

CARRUTHERS: I've told Carol you could spend some time with her. And we could catch bits and pieces with John today, here.

Scene II

Joni Mitchell and Doug Kershaw are sitting in a corner of the set. They are both guests on Cash's show.

JONI: I came here with Elliot, my manager, and Graham Nash. In the hotel we've been treated fantastically. The boys went out one day to get me a bouquet of flowers. They said everybody was hostile to them. People yelled - called them shaggy longhairs and hippies. They felt unsafe. I suppose that would happen in the Midwest, too. You can't blame it specially on the South.

ME: Doug, you've known Johnny Cash a long time. Everybody tells me he is a great human being. What do you feel gives him his special qualities?

DOUG: His upbringing. He believes in what his parents taught him.

ME: How about the new popularity of country music?

DOUG: The people performing it here used to be ashamed of it. Now we're proud.

ME: Have you met Dylan?

DOUG: We was writing songs together last night at the motel.

ME: How do you account for what seems to be his prevailing mood - tension?

DOUG: The man is so very human. You fail to realize that he's afraid. Deathly afraid.

JONI: Sometimes the most frightening thing is when everyone loves you too much. I can only tell you how I have felt. It puts you in this kind of a situation: suppose just before going onstage you get temperamental and you go into a rage. You yell at someone dear to you. Suddenly, you go onstage, and you're met by all those people who say, "Isn't she sweet?" And in your own head you're saying, I'm a monster, I just yelled at someone. That's when you lose your strength and you begin to hide. You feel everyone is seeing through you.

ME: Do you think this is what is happening to Dylan?

JONI: Yes, I do. You forget you're not dealing with stars. They are a different breed than an artist or poet. Dylan's such a sensitive guy. A star comes out and shows teeth and everything. He's doing like what I'm doing. I'm doing songs now where I've asked, please no orchestra, just guitar. Dylan said, "Please, no cardboard house behind me. Let me just have a plain background. It's me - not the background. No distractions."

ME: Do you feel cameras are distractions?

DOUG: It's directions, honey. Having to concentrate on, "You gotta do this or that." He's too sensitive for that. Who should know best how to present himself? If he was asked, he'd tell you how. No one asked. They showed him what to do. And he's too nice to argue.

JONI: He used to be better off when he was younger and an angry young man. And he would scream at you and diminish you if he thought your questions were stupid or inartistic. Now, he knows he can't be an angry young kid any more. He can't growl. Instead, he stays silent and explodes inside. Instead of taking it out on you, he takes it out internally. I really think that's what it is.

Scene III

The orchestra plays the same tunes over and over. Johnny Cash, saving his voice, whispers his songs and lines. Jeff Rose continues negotiations for us with some great unknown. I catch up twice with Cash, a big, awkward, nice man in overalls and sneakers, one of which he uses like an eraser on the floor. We perch on stools and are photographed.

ME: I understand Bob Dylan is doing this show as a· favor to you.

CASH: I guess so. I asked Bob if he'd be a guest on my TV show - I had a lot of friends I wanted to be on the show - and he agreed to do it. He hadn't done TV in years. He doesn't intend, to do any more TV. He doesn't intend to do any more concerts. Although he's talked with me about it, I really don't know what his plans are.

ME: Can you help us get to him?

CASH: No. I put a reporter on him yesterday and thought it would be all right, and it wasn't.

The reporter, I found out later, was Red O'Donnell from a Nashville newspaper. Cash tells me about his life and hard times: a childhood watching his mother break her back in the cotton fields; a terrible period when he found himself on a see-saw of soft drug addiction (up on Dexedrine, down on tranquilizers). Were his problems caused by a grueling work schedule of one-nighters? The tense world we all live in?

CASH: You could blame it on those things, or you might just call it weakness. There's no excuse.

ROSE (interrupting): Everybody is talking about the magnetism when you and Dylan sang together ...

CASH: Now, that's something everybody else sees, but I don't. At rehearsal yesterday he sat down beside me, and we just sang a song together. We've done it dozens of times just foolin' around. We had a dinner at our house with Nashville songwriters to meet Bob Dylan. We all sat around and sang songs together. The guitar was passed from one to another. It was handed to Bob. He did a couple of songs. Then I did a couple. Then I said, "Let's sing 'Girl of the North Country' like we did on the record, just for the hell of it. We just did it, that's all. We did it again yesterday at rehearsal, the first time since then. I knew my lines. He knew his. I didn't feel anything about it. But everybody here said it was the most magnetic, powerful thing they ever heard in their life. Just raving about electricity, magnetism. And all I did was sit there hitting G chords.

Scene IV

Later. On the way back from lunch with Wynn and Rose, I meet Red O'Donnell, the reporter. He is smiley, friendly, and dying to talk about his encounter with Dylan.

O'DONNELL: I was trying to open him up a little. I got him and put him in a room. It was a room where if I coulda locked the door ... I asked him, "Why are you so shy? "He said, "Let me think about that." I said, "All right, how do you explain your appeal to people? I know people who think you're a religion." And he thought a minute and said, "I wish I knew." Then he started talking about his songs; how he gets sparks and hears phrases, but he never explained why he was so shy. I asked him if he had any friends. Afterward Bob Johnston (producer of Dylan's records) said, "Why the hell did you ask him that? You acted like he was some weirdo.'' When I got back to Dylan later, he told me, "You know that question about my friends? It didn't upset me. They say he's scared. I think most of the people around him are scared.

Scene V

Back in the Opry House we meet Cash's manager, Canadian Saul Holiff, and associate producer Joel Stein.

STEIN: If Dylan says no pictures, you gotta live with it 'cause he'll walk off. It's like he's on the edge ....

HOLIFF: Did he intimate - ?

STEIN: No, but he's reacted in certain instances so you know his response would be that.

HOLIFF: I was with him when we hatched this whole idea of their appearing together. I don't think you'll have any trouble at all. He doesn't have to be here until 5. He hasn't been bugged by anybody.

STEIN: He· never mentioned pictures specifically. You never know. He could come in relaxed. I'm just trying to protect the situation.

EPILOGUE

June Cash in her dressing room tells me that Dylan isn't scared, just shy. She says, "The Dylans are very good friends of ours. John wants Bob to be comfortable. When they are with us, we just try to keep everybody away because we respect his privacy. But I never know quite what he's thinking. He's a small man, but when he walks into a room you can sense a bigness about him.

She talks about how much happiness her year-old marriage to Cash has given her. Her eyes fill up as she talks about her man. A sweet and gracious lady. But I get edgy as I look at my watch. It is almost five. Dylan time.

On stage everybody is just standing around waiting. I look outside the auditorium door where guards are already on duty. Nashville's well-scrubbed hippies are there waiting for Dylan.

Joni Mitchell's manager comes over and asks me what I'm going to do, because if you just go up and ask him for an interview, he'll freak you out.

We've been waiting a half hour. I hear shrieks from the Ivory babies. I turn around and feel something whiz by. Dylan has come and gone.

I rush backstage. Dylan is in the open-doored men's dressing room. He looks, after all those reports, surprisingly affable and relaxed. He's shaking hands with performers. I keep my distance. Dylan comes out. He's now a foot away from me. June Cash shows up. I am tempted to ask her to introduce me, but I don't want to muff whatever it is that Jeff Rose is supposed to be doing for me.

Dylan glances at me once. I am getting paranoid. I think he knows I'm a reporter, and that the look he's giving me is pure suspicion. I want to say: But I'm a nice girl. I like you . I like your songs. Won't you let me talk to you? We'd get along. I wouldn't push you - honest. Instead, I go to search for my mouthpiece, Jeff Rose. Rose is talking to Bob Johnston. The key man is out in the open at last . Johnson is talking about someone who looked upon Dylan as a freak. I assure him that I don't think Dylan is a freak . "I know that," says Johnson. "But right now he's got a TV show to do." "I know that," I say. "But I'm willing to wait until tomorrow - or whenever it's convenient."

"I'll ask him," says Johnson, taking off like a sudden Southern breeze.

I run into Johnny Cash. "How are you doing?" he asks .

"Not so good. I can't get to Dylan."

"I'll ask him later," he says.

Dan, Jeff, and I settle into first-row seats to watch the run-through. I tell them I'm going backstage. Jeff eyes me nervously. "Just the-ladies room," I assure him. Back there I hear some technicians talking. One is explaining Dylan: "He's not a hippie or anything. He's got a kind of bluesy, country sound."

The rehearsal schedule has Dylan on for 5. It is now 5:45. Dylan appears at six. On stage he doesn't look at ease anymore. He goes through the number woodenly, at one point raising his guitar as if it was a burden. He looks faintly happy only when it's over.

When it's finished our photographer jumps up on stage and back down again three times. They have to do the numbers over. Finally, the photographer is up there and nobody shoos him away. Dylan and Cash come to center stage.

Click, click, click.

The photographer pauses to adjust a lens. Dylan breaks away. It's all over. I know it's all over for me, too. All I have to write about are things that others said about him.

Don't you think, Bob Dylan, that it would be better for you to speak for yourself? I'd still go to the ends of the earth to hear you do it.

Copyright protected material on this website is used in accordance with 'Fair Use', for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner(s). Please read Notice and Procedure for Making Claims of Copyright Infringement.

Added to Library on November 9, 2015. (19080)

Comments:

Log in to make a comment