The year was 1969, and outdoor rock festivals were all the rage. Big ones, small ones, famous ones, forgotten ones. They were everywhere.

The two best known were on the coasts, Woodstock and Altamont. But Atlanta had a big one, as did Texas, Denver, Toronto and Newport. Britain had its Isle of Wight Festival with a memorable Bob Dylan appearance.

And New Jersey had the Atlantic City Pop Festival, held at the Atlantic City Race Course in Mays Landing. Thirty-five years ago today, in the heyday of peace and love, thousands of music fans had gathered at the track for the Friday-through-Sunday festival that featured some of rock's leading lights.

They included Janis Joplin, Creedence Clearwater Revival, the Jefferson Airplane, Santana, Joe Cocker, Butterfield Blues Band and Canned Heat. All would play at Woodstock two weeks later.

By the time Little Richard closed out the festival, more than 100,000 fans -- paying $6 for each day's admission in advance, 75 cents more on the day of the show or $15 for the event package -- had crammed onto the track's grounds. The track's official count was 111,470.

Depending on whose version you accept, dozens of others -- maybe a lot more -- crashed the gate in the freewheeling spirit of the day.

Many fans camped out in local campgrounds, along roads leading to the track or outside the gate; others took up quarters in motels or their vehicles; some attempted to bed down in the track's stables, while more than a few simply slept out under the stars.

Traffic on the Black Horse Pike and other roads leading to the site was snarled for long stretches, while the shelves at local stores and markets were picked clean. Food was also sold at the track, and concessionaires were given a handout alerting them to the possibility their patrons could look "somewhat bizarre."

Though drugs were available, incidents of unruliness were few and far between, according to accounts of the day. The worst incidents involved some pushing and shoving for a better view of the stage, the ransacking of a few booths at a makeshift flea market under the grandstand (billed as an "international youth exhibition"), littering and nude swimming in the track's infield lagoon.

To contend with the heat, the track pulled out its own hoses to spray down the crowd.

At one point, fans pushed so close to the stage that promoters thought about calling off the festival, recalled Glenn McKay, who was operating the light show for the Jefferson Airplane. McKay said he took the microphone in a last-ditch attempt to salvage the concert and asked everyone to take three steps back.

"I remember a tremendous feeling of power when thousands of people did as I asked," McKay recalled. "It was a pretty impressive sight."

To deal with major problems, the State Police set up a command post at a nearby high school, while officers in surrounding towns were on 24-hour call during the festival. The security measures were adopted after local residents and merchants expressed fears about being overrun by hippies and outlaw motorcycle gangs.

A medical tent treated the injured, with cuts and splinters the most frequent complaint. The Atlantic City Medical Center reported treating a couple of dozen drug cases.

All in all, it was pretty much Woodstock before Woodstock, though on a smaller scale (Woodstock's crowd was estimated at upwards of 400,000) and without the sea of mud and much of the hassle.

Except that Atlantic City also had in its lineup B.B. King, Joni Mitchell, Procol Harum, Frank Zappa, Chicago, Booker T & The MGs, the Chambers Brothers, the Byrds, the Moody Blues, Sir Douglas Quintet, Mother Earth, Lighthouse, Iron Butterfly, Tim Buckley, Dr. John, Hugh Masekela, Buddy Miles Express, Three Dog Night, Crazy World of Arthur Brown, Aum, American Dream and Lothar and the Hand People -- artists who didn't appear in upstate New York two weeks later.

Looking back, the Atlantic City Pop Festival can truly be considered New Jersey's Woodstock or, in another light, the biggest and best rock festival that hardly anyone remembers except those who were there.

"The Atlantic City festival was the stepping stone to Woodstock and should be viewed right alongside Woodstock," said Sheldon Kaplan, president of the Electric Factory, the concert promotion company that produced the festival.

Unlike Woodstock, the Atlantic City festival made a profit off its gate receipts, somewhere around $200,000 after expenses of more than $400,000, he added.

The Electric Factory had been promoting rock shows for a couple of years before the Atlantic City festival, mostly in Philadelphia at its Electric Factory club. But a few were mini-festivals at The Spectrum, Philadelphia's main indoor arena at the time.

The outdoor festival was the brainchild of Herb Spivak, one of three brothers who founded the Electric Factory and who'd started in the music business owning a jazz club. The idea for a festival had been swirling in his head when, driving back to Philadelphia from his summer home in Ventnor one day, he stopped by the racetrack and walked in on owner Bob Levy without an appointment.

The visit concluded with Spivak and Levy striking a deal for the track to host the festival.

"I remember telling him I'd have my lawyers call his lawyers to work out a contract, but he said, 'A handshake is good enough for me,'" Spivak recalled.

The track was the only site considered -- for reasons that should also have dawned on Woodstock's promoters.

"It was the largest outdoor site around that offered security," Kaplan said. "That was the key. The track was used to handling large crowds and had its own security force."

As part of the crowd-control plan, the grounds were cleared and the gates locked each night. The shows ran from early afternoon until after dark. Bands performed on a rotating stage facing the grandstand that permitted one act to set up while another was playing, keeping the music more or less continuous.

The dates for the festival were selected without regard to any other scheduled concerts, said Larry Magid, who booked acts for the Electric Factory at the time. As it was, the Atlantic City festival was sandwiched between the first -- and only -- Rutgers Jazz Festival at Rutgers Stadium the weekend of July 26-27 and Woodstock on Aug. 15-17.

The Rutgers event ended in a downpour just before Blood, Sweat and Tears took the stage to end the festival. Rain also plagued Atlantic City, but more at night than during the day.

Rain began falling just as Little Richard was on stage getting ready to close out the Atlantic City festival. To get things going before the weather got worse, Little Richard, Magid recalled, barked to his bandmates as they were tuning their instruments: "That's close enough, let's hit it."

Little Richard finished the set standing atop a piano that had been brought in specially for the festival, said Kaplan.

"He broke its lid, but by then, nobody cared," Kaplan said.

Because of its predominately rock lineup, the festival drew mostly white youths in their teens and early 20s. The promoters did little advertising and figured the show would draw primarily from the Delaware Valley.

Kaplan recalls one big advertising push as nothing more than sticking posters on poles along the Black Horse Pike. Promoters also sent a couple of kids with a car full of posters to some East Coast cities and got them air time on local radio stations to plug the festival, Spivak recalled.

Even without much of a public relations campaign, word of the concert spread, and music fans from many far-off states showed up at the track. Some were traveling the festival circuit and working their way toward Woodstock.

Peter Stupar recalled reading about the show in a now-defunct newspaper. He was 17 at the time and living in Potomac, Md. He said he talked a friend into hitchhiking with him to the track, leaving late Thursday and getting to the track by dawn opening day.

Stupar brought with him a 35mm Nikon camera that he'd rented for $15 for the weekend. Early on, he was mistaken for a legitimate press photographer and given prime access to the stage. By the time the festival was over, he'd taken 150 shots.

While he and his friend had plenty of money, they had no place to stay and ended up sleeping on the ground, even as it rained.

"When I got home, I was one soggy puppy," remembered Stupar, 52, who moved to San Francisco in 1973, got into the music business and continued taking concert photos. "But I remember protecting the Nikon and the film with my life. Thank God I did."

Going to the festival also helped persuade Larry Mazer to make music his career. He was 15 and living in Philadelphia when a friend's parents drove him and the other boy to the track.

"We went to check out the flea market when Santana and Joe Cocker were playing because we didn't know who they were," remembered Mazer, 50, who runs a management company in Voorhees and has represented Peter Frampton and Kiss over the years. "Can you imagine?"

Maxim Furek, now 57, had just come home from a tour in Vietnam, had a job at steel plant and was living in Berwick, Pa., when he decided to attend both the Atlantic City and Woodstock festivals before enrolling in college.

"They were great times," he recalled. "Wanderlust was in the air. It was such a wonderful thing to just pick up and hit the road."

Jim Miller was married, working as a pharmaceutical salesman and living in Turnersville when his wife's father used his union connections to get the couple tickets to the shows in the track's press box.

"Being inside was great when it rained," said Miller, who today runs the track's simulcast operation. "I remember parking the car one day when it rained and getting totally soaked by the time I made it to the gate."

The artists who played Atlantic City have murky memories of the event but look back fondly on what they can recall. Many had been on the festival circuit since the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967 gave birth to massive outdoor rock shows.

"Atlantic City was peaceful and harmonious, but mostly intimate," drummer Buddy Miles said from his home in Texas. "That's what made it so great. You want to establish a relationship with your audience, even when it's big, and I was able to do that there."

Over the years, Miles has led his own band and also performed and recorded with the likes of Jimi Hendrix, Carlos Santana, Stevie Wonder and Wilson Pickett.

A native of South Africa, trumpeter Masekela was one of the only jazz acts on the bill, but he said he and the rock audiences of the day -- from their distaste for the Vietnam War to their appetite for adventure -- enjoyed plenty of common ground.

"I was very anti-establishment, and the rock 'n' roll community loved me for it," said Masekela, reached on tour promoting his recently released autobiography "Still Grazing" (Crown). "I hung out with those people; I played all the rallies. We became friends."

Because promoters were still feeling their way with festivals in 1969, the shows tended to be disorganized and prone to last-minute decisions, said singer Tracy Nelson, who fronted Mother Earth.

"We did a lot of really fast tap dancing to get the job done," she remembered, speaking from her home in Tennessee.

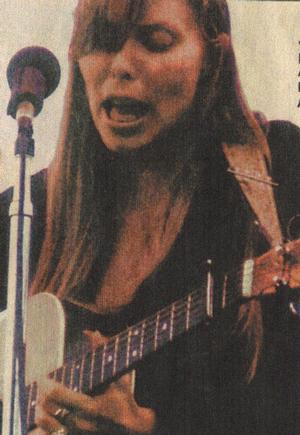

Fans recall Joni Mitchell walking off the stage in mid-set because she didn't think the audience was attentive enough, and an over-the-top Joplin removing her boots and throwing them into the crowd.

Joplin demanded a bottle of Southern Comfort before she went on and was paid $10,000 for her appearance -- the most of any performer -- while Mitchell initially only got half her fee until David Geffen, her manager, called and pressured the promoters for the rest, recalled Allen Spivak, 66, who took care of the festival's finances.

Magid feels the festival was important because it broke Santana as a national act (something Woodstock usually gets credit for) and opened the door for Little Richard, one of the original rock 'n' roll artists whose popularity ebbed in the '60s, to re-emerge as a major act.

Crosby, Stills and Nash were supposed to make their live debut at Atlantic City but passed in favor of Woodstock, claiming they weren't ready, Magid said. The Doors were the only group contacted about performing who turned the offer down, he added.

In the years after the festival, acts such as Santana and Joni Mitchell moved on to become major attractions, and still are. Others, like Iron Butterfly, were big names at the time but have slipped into obscurity since. B.B. King remains a popular touring act, as do Dr. John, the Moody Blues and Chicago.

The Byrds, Creedence and the Airplane -- to name a few -- broke up, while Joplin, Zappa, Buckley and Paul Butterfield are among those who've died.

While the track fell on hard times, the festival was a springboard for the Electric Factory to became a major player in the concert-promotion business.

The brothers were interested in doing another festival in Atlantic City the following year but, according to Herb Spivak, met with resistance from local officials, even though there was support in the business community. Their effort to stage a festival near the Delaware Water Gap in the same era met a similar fate, he added.

"We were outcasts, and nobody wanted any part of festivals because of what had happened at Woodstock," said Spivak, referring to the response of some public officials to the fiasco at the New York festival when many more people turned out than were expected.

Magid left the Electric Factory after the festival, but returned and eventually gained control of half the company, which was bought by SFX and sold to Clear Channel Communications in 2000. At 61, he continues working as a Clear Channel executive.

Kaplan left the music business in 1970 for the self-help movement. Today, he resides in Las Vegas and is involved with a nonprofit network to help people with addictions. A link to the group is contained in a Web site he's set up for the pop festival (www.acpopfestival.com).

At 66, Kaplan sometimes dreams about staging a revival of the Atlantic City event, figuring it would cost $2 million. When asked how much he calculated another festival might cost, Magid replied: "Can't count that high."

The Spivaks also sold their interests in the Electric Factory. Herb Spivak, 73, has gone on to several other successful non-music related businesses, while Allen has retired but sometimes gets involved producing a Broadway show. The third brother died.

While they say they never gave any thought to a movie or a soundtrack -- the likes of which helped turn Woodstock into the watershed event it has become in American pop culture -- Atlantic City's promoters insist they have no regrets over lost opportunities.

They're content, they say, to have put on a festival that was full of fun and free of major hardships for most who attended.

"If we'd had a little more rain and a little turmoil," Herb Spivak said, "Maybe we would have had the Woodstock thing."

Comments:

Log in to make a comment