Three days before her 53d birthday, Joni Mitchell had the eerie experience of confronting the spitting image of her younger self on a downtown stage.

It happened at the Fez, a nightclub in the East Village, where John Kelly was performing his acclaimed show "Paved Paradise," a drag homage to Ms. Mitchell. Dressed in a black turtleneck and black beret, the hair from a blond wig stringing down his face, Mr. Kelly sang some 20 Mitchell songs in an uncanny falsetto imitation of her yodeling folk-pop wail. For a second, Ms. Mitchell wondered whether she had died.

"I felt like Huck Finn attending his own funeral or Jimmy Stewart in that movie where the angel walks him back through his life," said Ms. Mitchell, who was in New York to promote two albums and to complete a book deal with Random House.

If "Paved Paradise," which reopens at Dance Theater Workshop on Jan. 2, is intensely loving, it's also sharply funny.

Mr. Kelly's vocal impersonation conveys an edge of caricature, and his two backup musicians are costumed as surreal cartoon parodies of Ms. Mitchell's muses, Vincent van Gogh and Georgia O'Keeffe.

"I was braced for a lampooning, and I didn't expect to be so touched," Ms. Mitchell recalled. "I cried in two places. During the song 'Shadows and Light,' my boyfriend and the woman who does my makeup and I were clutching each other and sobbing."

Ms. Mitchell, like Bob Dylan and Neil Young, is one of only a handful of singer-songwriters who rose out of the 1960's folk-music culture to become elder statesmen of rock. If none of their records sell as well as they did in the 70's (Ms. Mitchell's last gold album was "Don Juan's Reckless Daughter" in 1978), their status is such that the prestige they bring their record companies is considered well worth any loss of revenue.

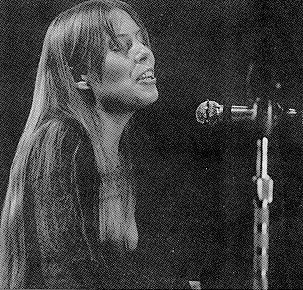

Since those early days, Ms. Mitchell has undergone a radical change of image from the wiltingly sensitive, flaxen-haired folk madonna from Canada who imagined "rows and flows of angel hair" in "Both Sides Now" to a biting social commentator, scornful of today's consumerism. Outspoken, cantankerous and often very funny (she does a hilarious Viennese accent to impersonate a pompous psychoanalyst), Ms. Mitchell, whose heroes range from Friedrich Nietzsche to Charles Mingus, unashamedly courts a solemn artistic mystique.

"She is like our Franz Schubert or Robert Schumann, a great art-song writer but working through the lens of popular culture," rhapsodized Mr. Kelly, who later in the week attended her birthday celebration in a Manhattan restaurant, where she presented him with a dulcimer. "To me her songwriting is infinitely more interesting than any of the serious classical composers I've heard in the past 20 years, aside from Leonard Bernstein."

Mr. Kelly's show may not be the most significant honor bestowed on Ms. Mitchell this past year, but it is probably the most heartfelt. As for more official recognition, lately it has been pouring in. Last December, Billboard, the record industry's leading trade magazine, awarded Ms. Mitchell its highest honor, the Century Award for creative achievement. Two months later, her album "Turbulent Indigo," won a Grammy for best pop album. In September, she was a recipient of the 1996 Governor General's Performing Arts Award, the most prestigious honor conferred upon Canadian performers.

Warner Brothers Records last month put out two anthologies of her work, "Hits" and "Misses," personally chosen collections of her music drawn from every phase of a recording career that began in 1968. Starting out in folk music, Ms. Mitchell went on to explore rock, African drumming, classical orchestration and several varieties of jazz. As she has crossed boundaries and experimented with various musical hybrids, she has come to define the singer-songwriter genre and earned the admiration of artists from all walks of music. And next month, she will be inducted into the Rock-and-Roll Hall of Fame, which had previously snubbed her.

During a recent interview in a Manhattan hotel, Ms. Mitchell touched on everything from the state of rock to confessional poetry to her own musical experiments. She was wearing her trademark black beret, a brown leather jacket and purple slacks, with a cigarette poised between lightly silvered fingernails: every inch the upscale bohemian troubadour.

But she expressed ambivalence about the Hall of Fame honor. "I don't know whether I should be proud or think it's silly, since rock-and-roll died so long ago," she said.

"Today's music isn't rock-and-roll. It's rock. It's Wagnerian, with white martial rhythm. There's no happy, rolling push beat to it."

A record company executive interrupted to inform Ms. Mitchell that the Rock-and-Roll Hall of Fame wanted another Canadian, Alanis Morissette, to introduce Ms. Mitchell at the January ceremony. Ms. Mitchell was undecided. In a recent interview in Details magazine, she had criticized Ms. Morissette's songwriting and later learned that Ms. Morissette had wept after reading her comments.

Wary of hurting any more feelings, Ms. Mitchell chose her words carefully in discussing the state of contemporary rock.

"I've forced myself to listen to hours and hours of contemporary rock broadcasts," she said. "For me, black music has a good beat, and some of the poets are quite articulate, but I'm sick of the 'hood, and I wish there was more diversity of message. As for the white aspect, the Northwest grunge is a lot of whiny, disinherited white boys. To me, the spirit of rock-and-roll has always been, 'It's Saturday night, and I just got paid and let's party.' And that's gone."

"I would rather tell you what I'm listening to than I would dis people," she continued. "Right now I'm listening to Debussy, the Sons of the Pioneers, who backed up Roy Rogers, and to some Stravinsky I'd overlooked."

As unsympathetic to today's rock as Ms. Mitchell may be, she remains an idol for several generations of younger rockers. "I'm 45," said Chrissie Hynde, "and it's comforting for people my age to know she's still there making music, trying to point out social injustices and whatever it is that makes a person human."

The three books Ms. Mitchell is working on will include a volume of song lyrics, a coffeetable book of her paintings and an autobiography.

But don't expect a tell-all naming lovers and settling old romantic scores.

"They want to know the celebrities I rubbed up against, but I told them that's not the most interesting part of my life," she explained "To me the most interesting things have been the synchronistic, mystical aspects. And the popularity of books like 'The Celestine Prophecy' shows there's a market for it. I want to start with a phase of my life that covers a four-year span and embraces my meeting Charles Mingus and Georgia O'Keeffe."

Eventually, Ms. Mitchell said, she can see herself writing several memoirs, each covering a different phase of her life.

Looking back on the period between 1971 and 1976, when she recorded her so-called confessional masterpieces -- records like "Blue" and "Court and Spark," which established her as the queen of Los Angeles rock -- Ms. Mitchell remembers it as the unhappiest period of her life, her "descent," as she calls it.

"I had no defenses," she recalled. "I found myself in the public eye, and I felt transparent. I could see through myself and through everybody else, and it was too much information for my nervous system to take. I cleared out the psychology and religious departments of several bookstores, searching for some explanation for what I was going through."

She also tried psychoanalysis, which, she said, she found unhelpful and dogmatic to the point of being ridiculous.

To this day she bridles at the application of the term "confessional" to her 1970's songs because to her, confession implies information extracted under duress. The term she prefers is "penitence of spirit." But while Ms. Mitchell calls herself a poet, she heatedly rejects any comparisons of her work to that of women like Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton.

"The only poets who influenced me were Leonard Cohen and Bob Dylan," she insisted. "What always bugged me about poetry in school was the artifice of it. When Dylan wrote, 'You've got a lot of nerve to say you are my friend,' as an opening line, the language was direct and undeniable. As for Plath and Sexton, I'm sorry, but I smell a rat. There was a lot of guile in the work, a lot of posturing. It didn't really get down to the nitty-gritty of the human condition. And there was the suicide-chic aspect."

In recent years, Ms. Mitchell has spent as much time painting as making music, and last year, during a period of writer's block, she decided to retire from music and even planned her farewell concert in New Orleans.

Less than a week before that final gig, a Los Angeles music merchant sent her a new computerized guitar called the Roland VG-8. The instrument contains an encyclopedia of guitar sounds, from those of Duane Eddy to Eric Clapton to Jimi Hendrix, and can also store the more than 55 tunings Ms. Mitchell has developed for the guitar, enabling her to retune the instrument by pressing a button. She is two-thirds of the way through recording an album that features the VG-8 and drums.

Ms. Mitchell, who is in the final stages of an amicable divorce from Larry Klein, the bassist with whom she produced several recent albums, is now involved with Don Freed, a musician and songwriter six years her junior who grew up in her hometown of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

She only recently embarked on what may be her ultimate personal quest, the search for a daughter she gave up for adoption when she was a struggling 20-year-old art school student in Canada. (Ms. Mitchell has no other children.) Two years ago, a British tabloid, working from clues dropped in her song lyrics, tracked down Ms. Mitchell's art-school roommate and paid her to tell the story of her illegitimate daughter.

The good news is that I'm clean now, and I have no skeletons," Ms. Mitchell said. "But I worry, because there are a lot of things she should know, her genetic background, what diseases she's prone to. It would be nice if she could meet her grandparents while they're still alive."

Ms. Mitchell's initial searches have produced what she calls "a lot of wannabes." Her celebrity, she said, has complicated the situation.

"I had my traumas in my 20's, and they're well documented," Ms. Mitchell said, and laughed. "I love my 50's."

But doesn't she ever miss those days when she was idolized as pop's beautiful, truth-telling goddess, the queen of L.A.?

"I slept through that queendom," she said quietly.

Was she even aware of her status at the time?

"It's hard to say," she replied. "It's better not to think about it."

Printed from the official Joni Mitchell website. Permanent link: https://jonimitchell.com/library/view.cfm?id=228

Copyright protected material on this website is used in accordance with 'Fair Use', for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner(s). Please read 'Notice and Procedure for Making Claims of Copyright Infringement' at JoniMitchell.com/legal.cfm