The Devil's Bargain

by Deborah Gangloff

American Forests

June

22,

2009

"We are stardust, Billion year old carbon,

We are golden, Caught in the devil's bargain"

Joni Mitchell, Woodstock 1969

I doubt that 40 years ago, Joni Mitchell knew that carbon would become a devil's bargain in 2009. While carbon and climate change shouldn't make us choose between the devil and the deep blue sea, many in the public policy arena would like us to think that a devil's bargain is our only choice when it comes to slowing climate change.

Since 1988, when the trend of excess atmospheric carbon dioxide as a threat to life on earth became clear, AMERICAN FORESTS has been planting trees to counteract [CO.sub.2] in our atmosphere through our Global ReLeaf campaign. But beyond carbon, our first priority is to restore forest ecosystems by replanting native trees to provide erosion control, clean the air of pollutants, buffer and filter our watersheds, and provide wildlife habitat. Yet, after 20 years and many battles, the war over the role of trees and forests in the solution to excess carbon is still not won.

Some would have us believe that trees and forests shouldn't count in the carbon fight, because their carbon benefits are too hard to quantify, too uncertain over the long term, and that they provide an easy way for polluting industries to avoid taking hard steps to reduce their carbon emissions. However, this perception ignores the huge potential value of trees and forests in carbon sequestration and storage, and works against forest restoration.

There are many issues surounding trees and forests and their role in fighting climate change. For a project to qualify for funds through a carbon market, the most important issue may be "additionality," or the net carbon benefit above and beyond what might naturally occur on the site without the project. In many places, trees do regenerate naturally after major natural disturbances, so it is fair to count only the carbon from those sites that exhibit a net increase above that which would occur naturally.

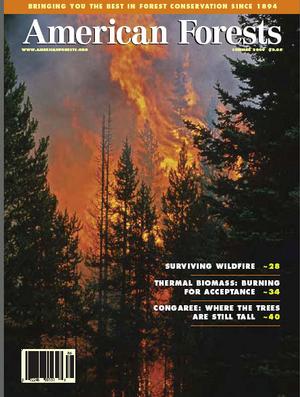

Much of our work is on sites burned intensely by wildfire, where natural seed sources are destroyed. Replanting these areas with trees will help bring back the forest, saving the land from a nonforest future and associated problems such as loss of habitat and increased erosion. Assisted reforestation also ensures that native species thrive, not just those species that blow in, which could be non-native or worse, invasive.

|

| Summer 2009 |

When AMERICAN FORESTS first received word of a major donation from ConocoPhillips to plant trees in California, we had a number of projects in the state that needed support. However, AMERICAN FORESTS was required to use the funds to support a project that would be approved under the forest protocol developed through the California Climate Action Registry (CCAR). That protocol is aimed at helping California meet its carbon goal set under its landmark legislation of 2002, the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Act.

The initial forest protocol required that an area must be without trees for 10 or more years to qualify for a reforestation project--presumably to confirm that natural regeneration had not taken place, and make it easier to count carbon gains. However, this precluded timely restoration of a site after a significant disturbance, such as intense wildfire.

In addition, the initial protocol did not allow for reforestation projects on public lands, which are the primary target for Global ReLeaf, especially in our California Wildfire ReLeaf campaign. All of our wildfire restoration projects in California are on lands that have burned recently, primarily in the fires of 2003 and 2006. So how could we identify and support a post-wildfire reforestation project on public lands under the existing forest protocol?

Fortunately, others also recognized these significant concerns. CCAR reconvened its forest working group, and two years later, proposals were developed to remove the barriers to post-disturbance reforestation projects on public lands.

At the same time, we found a project on the Cuyamaca Rancho State Park that will be submitted to the CCAR for approval once the revised forest protocols are adopted (see p. 17).

This innovative and collaborative project promises to become a national and international

example of a reforestation carbon-offset project to address climate change.

As Congress moves to enact clean energy and low carbon legislation, such as the Waxman-Markey bill (see p. 21), we need to ensure that trees and forests receive their due as a significant part of the solution to climate change. In addition to reforestation, other forest-sector projects can contribute to the solution. Forest conservation management, strategies to reduce wildfire emissions, putting woody biomass to practical use (see p. 34), and strategic tree planting in urban areas for energy conservation should count too. The devil may be in the details, but trees and forests can provide one way out of the devil's bargain on carbon.

Printed from the official Joni Mitchell website. Permanent link: https://jonimitchell.com/library/view.cfm?id=2256

Copyright protected material on this website is used in accordance with 'Fair Use', for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner(s). Please read 'Notice and Procedure for Making Claims of Copyright Infringement' at JoniMitchell.com/legal.cfm